By Dave DeWitt

On an August evening in A.D. 595, the Loma Caldera in what is now El Salvador erupted, sending clouds of volcanic ash into the Mayan agricultural village of Cerén, burying it twenty feet deep and turning it into the New World equivalent of Pompeii. Miraculously, all the villagers escaped, but what they left behind gives us a good idea of the life they led, the food they ate, and the chile peppers they grew.

The Ancient Ash

In 1976, while leveling ground for the erection of grain silos, a Salvadoran bulldozer operator noticed that he had plowed into an ancient building. He immediately notified the national museum, but a museum archaeologist thought that the building was of recent vintage and allowed the bulldozing to continue. Several buildings were destroyed. Two years later, Payson Sheets, an anthropologist from the University of Colorado, led a team of students on an archaeological survey of the Zapotitan Valley. He was taken to the site by local residents and quickly began a test excavation, and radiocarbon dating of artifacts proved that they were very ancient. He received permission from the government to do a complete excavation of Cerén. The site was saved.

|

The crew of the Cerén excavation,

|

Dr. Sheets and his students returned for five field sessions at Cerén, most recently in 1996. Their discoveries are detailed on their web site http://ceren.colorado.edu . One of the most interesting things they discovered was, in the words of Dr. Sheets, “We had no idea that people in the region lived so well 14 centuries ago.”

The ash preserved the crops in the field, leaving impressions of the plants. The plants then rotted away, leaving perfect cavities, or molds. Using techniques that were developed at Pompeii, the archaeologists poured liquid plaster into the cavities. By removing the ash, the ancient fields were revealed and could be studied. Interestingly, the Native Americans of Cerén used row and furrow techniques similar to those still utilized today; corn was grown in elevated rows, and beans and squash were grown in the furrows in between. In a courtyard of a building, “We even found a series of four mature chile plants with stem diameters over 5 centimeters (2 inches),” wrote Dr. Sheets. “They must have been many years old.” Chile peppers are rarely found in archaeological sites in Mesoamerica, so imagine the surprise of the researchers when they discovered painted ceramic storage vessels that contained large quantities of chile seeds. “One vessel had cacao seeds in the bottom, and chiles above, separated by a layer of cotton gauze,” Dr. Sheets revealed. “It is possible that they would have been prepared into a kind of mole sauce.” Also found were corn kernels, beans, squash seeds, cotton seeds, and evidence of manioc plants and small agave plants, which were used for their fiber to make rope rather than being fermented for an alcoholic beverage, pulque, as was done in Mexico.

|

A plaster cast of a chile stem with a 2-inch diameter

|

I emailed Dr. Sheets, hoping to discover the shape and size of the chiles and thus deduce the variety being grown. But no whole pods were found, just the seeds and some pod fragments. The size of the chile stem indicated that the plant had been grown as a perennial, but all chile plants are perennial in tropical climates and can grow to considerable size.

|

A polychromatic vessel like this one held stored chile seeds

|

Dr. Sheets wrote me back about an article by Dr. David Lentz, the botanist who had studied the plant remains, and I tracked it down in the journal Latin American Antiquity that I found in the Zimmerman Library at the University of New Mexico. Dr. Lentz wrote about the seeds and the pod fragments, “It appears that many of these fell from the rafters of buildings where they would have been hung for drying or storage.” He added that the chile seeds from the site were the first in Central America found outside Mexico, and he speculated that those seeds in vessels were probably being saved for future planting.

The Taming of the Wild Chile

But what kind of chile was grown in Cerén? There was an intriguing clue in the article: a photograph of a chile seed compared with a bar indicating the length of one millimeter. The seed was 3.5 millimeters wide. Since the size of the seed is directly related to the size of the pod (generally speaking, the larger the pod, the larger the seed), perhaps it was possible to guess the size of the pod by comparing that ancient seed to seeds I had stored in my greenhouse.

Paleoethnobotanists, the scientists who study the plants used by ancient civilizations, have theorized that chiles were first used as “tolerated weeds.” They were not cultivated but rather collected in the wild when the fruits were ripe. The wild forms had small, erect fruits which were deciduous, meaning that they separated easily from the calyx and fell to the ground.

During the domestication process, whether consciously or unconsciously, early Native American farmers selected seeds from plants with larger, non-deciduous, and pendant fruits. The reasons for these selection criteria are a greater yield from each plant and protection of the pods from chile-hungry birds. The larger the pod, the greater will be its tendency to become pendant rather than to remain erect. Thus the pods became hidden amidst the leaves and did not protrude above them as beacons for birds. The selection of varieties with the tendency to be non-deciduous ensured that the pods remained on the plant until fully ripe and thus were resistant to dropping off as a result of wind or physical contact. The domesticated chiles gradually lost their natural means of seed dispersal by birds and became dependent upon human intervention for their continued existence.

Because chiles cross-pollinate, hundreds of varieties of the five domesticated chile species were developed by humans over thousands of years in South and Central America. The color, size, and shape of the pods of these domesticated forms varied enormously. Ripe fruits could be red, orange, brown, yellow, or white. Their shapes could be round, conic, elongate, oblate, or bell-like, and their size could vary from the tiny fruits of chiltepins or tabascos to the large pods of the anchos and pasillas. But very little archaeological evidence existed to support these theories until the finds at Cerén.

An Educated Guess

It was exciting to think that perhaps we had a window into the ancient chile domestication process. Because their seeds were collected, and the plants were growing in a courtyard, the chile plants at Cerén were obviously cultivated and were more than just “tolerated weeds.” It was time to break out my metric ruler and start measuring seeds. I came up with the following table, ranked by seed width:

| Variety

Ancho Serrano Jalapeño De arbol Habanero Piquin Cerén Chiles Chiltepin |

Pod Length

12 cm 7 cm 6.5 cm 4.5 cm 4.5 cm 1.3 cm ? 0.5 cm |

Seed Width

6 mm 5 mm 5 mm 4.5 mm 4 mm 4 mm 3.5 mm 3 mm |

The first conclusion I reached was that the Cerén chiles were small-podded. They certainly were not as large as anchos, whose seeds are twice the width of those of the Cerén chiles. They could, of course, have been chiltepíns, because the seeds were only half a millimeter wider than chiltepín seeds. But if they were somewhere between the size of chiltepíns and piquins, that would have made the pods about 1 centimeter long, less than half an inch. And since there is evidence that the chile pods had been hung up to dry with agave twine, that process would quickly dry the small-podded plants and their fruits.

The correlation between seed size and pod length is not exact. Note that the habanero, which is nine times the length of the chiltepín, has seeds only 1 millimeter wider. Also note that the de arbol variety, which is also 4.5 cm long, but much thinner, has seeds only 1 millimeter wider than the Cerén chiles. I believe that we are witnessing the early domestication process begun by the Maya people. The complete domestication of chiles from chiltepíns to anchos and the development of many varieties would not happen until the Aztec culture of nearly a millennium after A.D. 595. This is my personal theory, and I am not a paleoethnobotanist, though sometimes I wish I had studied that discipline.

The Cuisine of Cerén

In addition to the vegetable crops of corn, chiles, beans, manioc, cacao, and squash, the archaeologists found evidence that the Cerén villagers also harvested wild avocados, palm fruits and nuts, and certain spices such as achiote, or annatto seeds. In fact, Dr. Sheets observed, “The villagers ate better and had a greater variety of foodstuff than their descendants. Traditional families today eat mostly corn and beans, with some rice, squash, and chiles, but rarely any meat. Cerén’s residents ate deer and dog meat.” They also consumed peccary, mud turtle, duck, and rodents, but deer was their primary meat. Fully fifty percent of the total bones found on the site belonged to white-tailed deer, and many of those deer were immature animals–giving rise to a very interesting theory.

Linda Brown, who wrote the 1996 Field Season Preliminary Report entitled “Household and Village Animal Use,” noted, “Cerén residents may have practiced some form of deer management. One of the deer procurement strategies the Cerén villagers may have utilized is ‘garden hunting.’ Garden hunting consists of allowing deer to browse in cultivated fields and household gardens where they can be hunted. While some vegetation is lost to browsing, the benefits include easy access to deer when needed.” Expanding upon that theory, she wrote, “The ethnohistoric data make many references to the Maya partially taming white-tailed deer. Specifically, historical sources note that it was women who were responsible for taking in, semi-taming, and raising deer. [Diego de] Landa mentioned that women raise other domestic animals and let the deer suck their breasts, by which means they raise them and make them so tame that they never will go into the woods, although they take them and carry them through the woods and raise them there. Apparently, during historic times, there was a designated place in the woods where women would take deer to browse until they needed them. Scholars have argued that pre-Columbian women may have raised deer, dogs, peccary, and fowl much like contemporary Maya women raise pigs and fowl for food, trade, and special occasion feasts. Perhaps the Cerén women raised dog, fowl (a duck was tethered inside the Household 1 bodega), and semi-tamed deer as a contribution to the domestic and ceremonial economy.”

It is always a challenge for archaeologists to reconstruct ancient cuisines and cooking techniques. The Cerén villagers did not have metal utensils, but they did have fired ceramics that could be used to boil foods. They could grill over open flames, and perhaps fry foods in ceramic pots using cotton seed oil or animal fat. They had obsidian knives that could cut as cleanly as metal. They had metates for grinding corn into flour and mocaljetes for grinding fruits, vegetables, chiles, and spices together into sauces.

|

An artist’s rendering of what an

|

Based on the archaeological evidence, I have devised some recipes that reflect the main ingredients used in the cooking of Cerén, adapted, of course, for modern kitchens. One of my basic theories about the history of cooking is that we should never underestimate our predecessors’ culinary sophistication, so I cannot presume that 14 centuries ago the Maya were preparing boring food. Especially since we know that they had chiles.

Recipes

Royal Chocolate with Chile

Although this drink was served to royalty in the large Mayan cities, the discovery of chile in conjunction with cacao in Cerén indicates that even commoners knew how to make this concoction.

- 1 ½ cups water

- 1/4 cup cocoa

- 1 tablespoon honey

- 1/4 teaspoon hot chile powder, such as piquin

- 1 vanilla bean pod

In a pan, heat the water to boiling. Add the remaining ingredients and stir well. Serve immediately with the vanilla bean for garnish in the drink.

Yield: 1 serving

Heat Scale: Medium

The Earliest Mole Sauce

Why wouldn’t the cooks of Cerén have developed sauces to serve over meats and vegetables? After all, there is evidence that curry mixtures were in existence thousands of years ago in what is now India, and we have to assume that Native Americans experimented with all available ingredients. Perhaps this mole sauce was served over stewed duck meat, as ducks were one of the domesticated meat sources of the Cerén villagers.

- 4 tomatillos, husks removed

- 1 tomato, toasted in a skillet and peeled

- ½ teaspoon chile seeds

- 3 tablespoons pepitas (toasted pumpkin or squash seeds)

- 1 corn tortilla, torn into pieces

- 2 tablespoons medium-hot chile powder

- 1 teaspoon achiote (annatto seeds)

- 3 tablespoons vegetable oil

- 2 cups chicken broth

- 1 ounce Mexican or bittersweet chocolate

In a blender, combine the tomatillos, tomato, chile seeds, pepitas, tortilla, chile powder and achiote to make a paste. In a pan, heat the vegetable oil and fry the paste until fragrant, about 4 minutes, stirring constantly. Add the chicken broth and the chocolate and stir over medium heat until thickened to desired consistency.

Yield: About 2 ½ cups

Heat Scale: Medium

Venison Steak with Juniper Berry and Fiery Red Chile Sauce

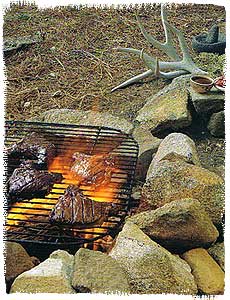

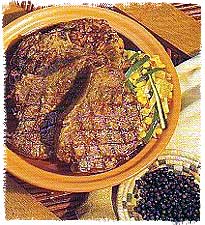

|

Venison steaks on the grill

Steaks served

(photos by Lois Ellen Frank)

|

|

This recipe is by Lois Ellen Frank, from her book Foods of the Southwest Indian Nations (Ten Speed Press, 2002). Both the venison and the juniper berries are available from mail-order sources. Of course, grape juice or wine would not have been available to the Maya, but Lois has adapted this recipe for the modern kitchen.

The Sauce

- 1 tablespoon dried juniper berries

- 3 cups unsweetened dark grape juice or wine

- 2 bay leaves

- 1 ½ teaspoons dried thyme

- 2 shallots, peeled and coarsely chopped

- 2 cups beef stock

The Steaks

- 6 venison steaks, 8 to 10 ounces each

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 tablespoon salt

- 1 tablespoon freshly ground black pepper

- 4 whole dried chiles de arbol, seeds and stems removed, crushed

To make the sauce, wrap the juniper berries in a clean kitchen towel and crush them using a mallet. Remove them from the towel and place them in a saucepan with the grape juice or wine, bay leaves, thyme and shallots. Simmer over medium heat for 20 to 25 minutes, until the liquid has been reduced to 1 cup. Add the stock, bring to a boil, then decrease the heat to medium and cook for another 15 minutes until the sauce has been reduced to 1 ½ cups. Strain the sauce through a fine sieve and keep it warm.

Brush the steaks on both sides with the olive oil and sprinkle with salt and pepper. Place the steaks on the grill and grill for 3 minutes, until they have charred marks. Rotate the steaks a half turn and grill for another 3 minutes. Flip the steaks over and grill for another 5 minutes until done as desired.

Ladle the sauce onto each plate, top with the steaks, pattern-side up, and sprinkle the crushed chiles over them.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Pepita-Grilled Venison Chops

Here is a tasty grilled dish featuring native New World game, chiles, and tomatoes, plus pepitas–toasted pumpkin or squash seeds. Garlic is not native to the New World, but is given here as a substitute for wild onions, which the people of Cerén would have known.

- 5 tablespoons pepitas

- 3 cloves garlic

- 1 tablespoon red chile powder

- ½ cup tomato paste

- 1/4 cup vegetable oil

- 3 tablespoons lemon juice or vinegar

- 4 thick-cut venison chops, or substitute thick lamb chops

Puree all the ingredients, except the venison, in a blender. Paint the chops with this mixture and marinate at room temperature for an hour.

Grill the chops over a charcoal and piñon wood fire until done, basting with the remaining marinade.

Yield: 4 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Cerén Beans

Three varieties of beans were found beneath the ash in the village kitchens of Cerén. Certainly they were boiled, and since they are bland, they were undoubtedly combined with other ingredients, including chiles and primitive tomatoes. The Cerén villagers would have used peccary fat for the lard and bacon, and of course would not have had cumin. But they probably would have used spices such as Mexican oregano.

- 3 cups cooked pinto beans (either canned or simmered for hours until tender)

- 1 onion, minced

- 2 tablespoons lard, or substitute vegetable oil

- 5 slices bacon, minced

- 3/4 cup chorizo sausage

- 1 pound tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped

- 6 serrano chiles, stems removed, minced

- 1 teaspoon cumin (or substitute Mexican oregano)

Saute the beans and onion in the lard or oil for about five minutes, stirring constantly. In another skillet, saute the bacon and chorizo together. Drain.

Combine the beans and onion with the drained bacon and chorizo in a pot, add the other ingredients, and simmer for 30 minutes.

Serves: 4

Heat Scale: Medium

Spicy Calabacitas

This recipe combines three Native American crops: squash, corn, and chile. Although we don’t know for sure, my theory is that the Cerén villagers would have known how to use green chile. I have taken the liberty of substituting New Mexican chiles for the small Cerénean chiles, making a milder dish. The villagers, of course, would not have used butter, milk, or cheese, but rather fat and water flavored with palm fruits.

- ½ cup chopped green New Mexican chile, roasted, peeled, stems removed

- 3 zucchini squash, cubed

- ½ cup chopped onion

- 4 tablespoons butter or margarine

- 2 cups whole kernel corn

- 1 cup milk

- ½ cup grated Monterey Jack cheese

In a pan, saute the squash and onion in the butter until the squash is tender.

Add the chile, corn, and milk. Simmer the mixture for 15 to 20 minutes to blend the flavors. Add the cheese and heat until the cheese is melted.

Yield: 4 to 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium