By Rick Hendricks

[Editor’s Note: This essay is excerpted with permission from Sunshine and Shadows in New Mexico’s Past: The Statehood Period 1912-Present, published by Rio Grande Books (www.RioGrandeBooks.com) in collaboration with the Historical Society of New Mexico.]

New Mexico is the only state in the United States that boasts a state question: “red or green?” While such a question may seem odd to outsiders, every New Mexican knows that this question refers to a preference of the state’s favorite food: chile. Indeed, chile has become central to the diet, culture, economy, and very identity of the state since at least 1913, the year following the achievement of statehood. The indisputable dominance of a single food was made possible by the work of two devoted scientists working at New Mexico State University: Fabián García and Roy Nakayama. Separately, they developed new, increasingly popular and marketable varieties of chile. Together they richly deserve to be known as the “chile kings” of New Mexico.

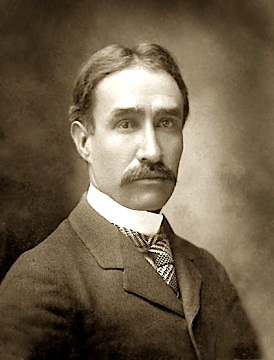

Fabián García

Fabián García was born in Chihuahua, Mexico on January 20, 1871, to Ricardo García and Refugio Romero de García.1 Orphaned of both parents soon after his birth, García moved to the Mimbres Valley in southwestern New Mexico with his paternal grandmother, Jacoba García, when he was two years old. Jacoba found work in the home of George Wilson and his wife in San Lorenzo in Grant County.2 They later moved to the home of Mr. and Mrs. R. J. White in Georgetown, near Santa Rita. There he received his first schooling. He came to the Mesilla Valley in 1885 with his grandmother who found employ with the Thomas Casad family. The Casads provided the opportunity and financial support for García to further his education through formal schooling. The fact that the Casad Orchard was one of the largest fruit-growing enterprises in the Mesilla Valley offered García practical experience working with orchard crops and the pests associated with them. Evidence of this experience is clear in his later research and writing. When Las Cruces College opened in 1888, García was said to have appeared with his McGuffey Reader in hand and sought admission.3

Fabián García was born in Chihuahua, Mexico on January 20, 1871, to Ricardo García and Refugio Romero de García.1 Orphaned of both parents soon after his birth, García moved to the Mimbres Valley in southwestern New Mexico with his paternal grandmother, Jacoba García, when he was two years old. Jacoba found work in the home of George Wilson and his wife in San Lorenzo in Grant County.2 They later moved to the home of Mr. and Mrs. R. J. White in Georgetown, near Santa Rita. There he received his first schooling. He came to the Mesilla Valley in 1885 with his grandmother who found employ with the Thomas Casad family. The Casads provided the opportunity and financial support for García to further his education through formal schooling. The fact that the Casad Orchard was one of the largest fruit-growing enterprises in the Mesilla Valley offered García practical experience working with orchard crops and the pests associated with them. Evidence of this experience is clear in his later research and writing. When Las Cruces College opened in 1888, García was said to have appeared with his McGuffey Reader in hand and sought admission.3

García became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1889 when he was eighteen years old and began coursework at New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in 1890. Although a slight young man, García played on the New Mexico A&M football team.4 He was a member of the college’s first graduating class in 1894, earning a bachelor´s of science degree. García participated in the first Farmer’s Institute, held in Las Cruces on January 2-4, 1896, where he gave a paper on meteorology. Upon graduating with his bachelor’s degree, García became an assistant in agriculture. García did special graduate study at Cornell University during the 1899-1900 school year. Among the classes he took there were: Animal Industry, Dairy Husbandry, Evolution of Cultured Plants, Literature of Horticulture, and Propagation of Plants.5

In 1906 he earned a M. S. A. at New Mexico A&M. After earning his master’s, García was named professor of horticulture and horticulturist at the experiment station. In his early years as an educator, García taught landscape gardening, olericulture, and pomology. Best known for his work in agriculture, García was also a keen entomologist. He often sent specimens to learned institutions around the United States, seeking information or adding to their collections. In 1907 a new American bee was named for him—Nomada (Micronomada) garciana.6 The habitat of this bee was listed as the College Farm in Mesilla Park, where García had obtained a specimen on May 1, 1907.

Fabián married Julieta J. Amador on August 14, 1907. She was daughter of Martín Amador, one of the most prominent citizens of the Mesilla Valley.7 In May 1908, García was preparing to build a house on land he owned facing the railroad depot by having a supply of adobes made.8 As time went by, he acquired numerous pieces of property throughout Las Cruces and Mesilla Park.

García spent the first two weeks of October 1908 with his colleague J. D. Tinsley in Albuquerque where they were in charge of the Doña Ana County exhibit at the New Mexico Territorial Fair.9 Tinsley was the vice-director of the New Mexico Agricultural Experiment Station in Las Cruces. García was often called upon to be a judge at such fairs and was frequently involved in preparing exhibits from the college.

Julieta gave birth to a son they named José. Their joy was to be short lived. José was born on May 4 and died on May 17, 1909. He is buried in the San José Cemetery in Las Cruces in the Amador plot on the south side of the mausoleum.

Beginning in January 1912, García participated with his colleagues at New Mexico A&M in the Cultural Train, a traveling demonstration of exhibits from the school that took a fifteen-day railroad excursion through New Mexico.10 The aim of the Cultural Train was to promote better farming in New Mexico and to spread the idea that the children of today are the farmers of tomorrow. When the train stopped, farmers gathered to look at the exhibits and listen to lectures on best farming practices.

Another scholarly endeavor to which García dedicated his time and energy was the editorial side of the publishing world. In 1912 he became editor on agriculture and horticulture for The Mid-Continent Magazine, which was based in Denver, Colorado.11 In the 1920s he was listed as a staff specialist for a newspaper called the Rio Grande Farmer.12 In addition to his editorial duties, García also contributed articles to both publications.

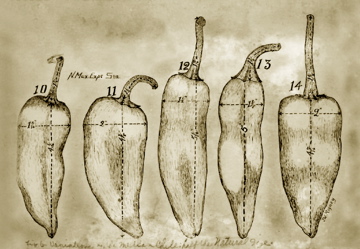

In 1913 García became director of the experiment station. The promotion made him the first Hispanic in the nation to lead a land-grant agricultural research station. In that year García released ‘New Mexico No. 9’, historically the most important chile cultivar because it was the first developed at New Mexico A&M and because it introduced a new pod type called New Mexico.13 García had begun selecting for what would become the New Mexico pod by improving chiles grown locally in the Las Cruces area. Before García initiated his research, growers had no way to predict or control the size or heat of chile pods. García thought that milder chiles would appeal more to non-Hispanics and therefore increase consumption. He also sought to develop a chile characterized by “a fleshy, smooth, tapering, and shoulderless pod.”14 Such a chile would be easier to peel after roasting and to can. To accomplish his goal, García selected fourteen chile accessions growing in the Las Cruces area and by selection and hybridization began to eliminate lines with less desirable characteristics. After nine years of work during which some crops were largely lost to chile wilt, only ‘New Mexico No. 9’ remained. Although not as hot as most improved varieties, García judged ‘New Mexico No. 9’ to be hot enough.

In 1913 García became director of the experiment station. The promotion made him the first Hispanic in the nation to lead a land-grant agricultural research station. In that year García released ‘New Mexico No. 9’, historically the most important chile cultivar because it was the first developed at New Mexico A&M and because it introduced a new pod type called New Mexico.13 García had begun selecting for what would become the New Mexico pod by improving chiles grown locally in the Las Cruces area. Before García initiated his research, growers had no way to predict or control the size or heat of chile pods. García thought that milder chiles would appeal more to non-Hispanics and therefore increase consumption. He also sought to develop a chile characterized by “a fleshy, smooth, tapering, and shoulderless pod.”14 Such a chile would be easier to peel after roasting and to can. To accomplish his goal, García selected fourteen chile accessions growing in the Las Cruces area and by selection and hybridization began to eliminate lines with less desirable characteristics. After nine years of work during which some crops were largely lost to chile wilt, only ‘New Mexico No. 9’ remained. Although not as hot as most improved varieties, García judged ‘New Mexico No. 9’ to be hot enough.

Although García’s professional life was thriving, his personal life was again touched by tragedy. Julieta Amador de García died at the home of her sister, Mrs. A. N. Daguerre, in El Paso on Sunday, December 5, 1920.15 Although she was suffering from bronchitis and her condition was considered grave, her death came suddenly and unexpectedly. García never remarried, and his involvement in the activities of New Mexico A&M seemed to occupy most of his time.

In 1927 New Mexico A&M conferred an honorary doctorate of agriculture on García in recognition of his “outstanding work in developing New Mexico agriculture.”16 The U. S. Department of Agriculture invited García to participate in a trip to Mexico where he led a lecture course on agricultural education and education. In 1943 he received an honorary doctorate of science from the University of New Mexico.

At their meeting on March 24, 1945 the A&M Board of Regents retired García.17 Dean John William Branson announced that the action was taken because of García’s failing health. García had been ill for seven months with Parkinson’s Disease and was receiving treatment at McBride Hospital in Las Cruces. When he was retired García was given emeritus status at the college. By formal resolution the experiment station’s horticulture farm was given the name Fabián García Farm.

Fabián García died on August 6, 1948.18 He is buried in the Masonic Cemetery in Las Cruces. His will provided $89,000 to pay part of the $400,000 cost of construction of a men’s dormitory and provide scholarships to worthy Hispanic students that would enable them to live in the new dormitory. After subtracting the costs of liquidating his estate, the college realized between $84,000 and $85,000.19 The new dormitory, Fabián García Memorial Hall, was dedicated on Monday, October 17, 1949.

Through his work at the experiment station, García was credited with having added to the economic value of New Mexico agriculture, particularly with his research and development of chile, sweet potatoes, pecans, yellow and white Grain onions, and improved varieties of cotton. He authored twenty experiment station bulletins and co-authored another fifteen with Joseph W. Rigney and Austin B. Fite. In addition he wrote numerous newspaper and magazine articles.

In 2005 the American Society for Horticultural Science Hall posthumously elected Fabián García to its Hall of Fame. His plaque at the society’s headquarters in Alexandria, Virginia, reads “Dr. Fabian Garcia, a man of humble origins, but a gentleman of extraordinary achievements.”20

Roy Minoru Nakayama

Although the circumstances are unknown, Fabian García must have met the young man who was destined to carry on his legacy of chile research. That individual, Roy Minoru Nakayama, was born on September 11, 1923, to John K. and Tome Nakayama, both of whom had been born in Japan. At the time of his birth, Roy was the fifth of seven children. He would eventually have one more sibling, bringing the total number of children to eight.21 Roy’s father was born Kaichiri Nakayama in 1879 in Toyama Prefecture, which is on the coast of the Sea of Japan on Honshu Island.22 He left Japan in 1908 in search of opportunity. After arriving in Seattle, Kaichiri added John to his name. Partnering with a German immigrant named W. W. Peters, he relocated to a farm near Mitchell, Nebraska. After he was settled, John sent to Japan for Tome Miaguchi, the younger sister of his former traveling companion, to come to Nebraska to be his bride. When she arrived in 1915 Tome was twenty years old and sixteen years younger than John.23 The daughter of a doctor, Tome was used to a life of privilege and status.

Although the circumstances are unknown, Fabian García must have met the young man who was destined to carry on his legacy of chile research. That individual, Roy Minoru Nakayama, was born on September 11, 1923, to John K. and Tome Nakayama, both of whom had been born in Japan. At the time of his birth, Roy was the fifth of seven children. He would eventually have one more sibling, bringing the total number of children to eight.21 Roy’s father was born Kaichiri Nakayama in 1879 in Toyama Prefecture, which is on the coast of the Sea of Japan on Honshu Island.22 He left Japan in 1908 in search of opportunity. After arriving in Seattle, Kaichiri added John to his name. Partnering with a German immigrant named W. W. Peters, he relocated to a farm near Mitchell, Nebraska. After he was settled, John sent to Japan for Tome Miaguchi, the younger sister of his former traveling companion, to come to Nebraska to be his bride. When she arrived in 1915 Tome was twenty years old and sixteen years younger than John.23 The daughter of a doctor, Tome was used to a life of privilege and status.

The first child of John and Tome Nakayama was a boy they named Carl, who was born in Nebraska. While working on the farm John injured his ribs, and after he healed was no longer able to tolerate the cold the Great Plains. So the family departed for southwest Texas to look over some land belonging to Peters. Near El Paso, Tome, who was expecting her second child, became seriously ill. Her long recovery required money, so John rented farmland that had belonged to the utopian community called Shalam Colony, eight miles north of Las Cruces. Roy was born there in what had been the Children’s House.

By 1925, John had save enough money to purchase land, but he had to register it in Carl’s name because the New Mexico alien land law (1918) and the Oriental Exclusion Act (1924) forbade foreign born Asians from owning land. John’s original twenty-five-acre farm eventually grew to 105 acres and several hundred acres of leased land. When Carl turned twenty-one in March 1937, the Nakayama family finally owned their own land.

Roy enrolled in Las Cruces Union High in 1937 becoming the fifth Nakayama to attend the school. His best courses were vocational agriculture and those designed for members of the Future Farmers of America (FFA). His real passion during his high school years, however, was said to be tennis.24 Still, Roy intended to be a farmer following in the footsteps of his father, who operated a commercially successful truck farm in the Mesilla Valley.25

Athletics might have been his favorite pursuit, but livestock judging was what won him recognition in his teenage years. In February 1939 fifteen-year-old Roy was on the winning livestock judging team at the Southwestern Livestock Show in El Paso representing Las Cruces Union High School’s FFA that took home the H. A. Tolbert Memorial trophy.26 He participated on the school’s livestock judging team that captured a state championship in 1939. Roy was one of five hundred FFA members gathered in Las Cruces for the annual convention in April 1939. He participated in judging dairy cows.27

Roy purchased two Rambouillet ewes in December 1939 and planned to gradually increase the size of his herd. Because of his interest in fine wool breeds he was beginning with a breed that had its origins in the Spanish Merino.28 Later in the month he took third place at the annual inter-class FFA livestock judging competition in Las Cruces and was awarded a gold-plated watch fob.29 At the 1940 Southwestern Livestock Show in El Paso, again representing Las Cruces Union High School FFA, Roy exhibited in the category of fat lambs. Because Roy was on the winning team from the previous year, he was not eligible to compete in livestock judging.30

After high school Roy attended New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (NMA&M) for two years.31 In October 1942 he enlisted in the United States Army and was called to active duty in 1943. While awaiting orders for assignment, Nakayama attended college at Sam Houston State Teachers College in Huntsville, Texas, for a year.

Company D, 159th Infantry Division left for Europe on September 28, 1944. Nakayama was a participant in the Battle of the Bulge, which began in mid-December 1944, where he was captured. He spent seven months in captivity before being liberated east of Wiesbaden, Germany. At the time of his liberation, Nakayama weighed only eighty-seven pounds. According to his wife, Rose, after his experience as a prisoner of war, Roy could never get warm or endure farm work.

Back in New Mexico, Nakayama decided to return to school but was refused admission on the grounds that he was Japanese. His former professors intervened on his behalf and demanded his admission to the college. Nakayama earned his B.S. in Botany from NMA &M in 1948. He began advanced studies at Iowa State College in the fall of 1948 and received his master’s in plant pathology on August 26, 1950.32 Nakayama remained enrolled through the fall semester of 1951. Apparently, he then went to work for the California State Department of Agriculture. He reenrolled in 1957 and continued graduate work until he received his doctorate in plant pathology from Iowa State University on February 27, 1960, although much of this time he was in Las Cruces and in the employ of NMA&M, having come back to the college in 1956.33

Nakayama taught intermediate and advanced classes in the horticulture department. In addition to his research in vegetable breeding, he served as a consultant for the NMSU-US Agency for International Development joint program in Paraguay, setting up horticultural research and teaching programs at the University of Asunción.

Beyond his research and teaching activities, Nakayama was a sportsman. Playing to a fifteen handicap after only a year of serious play, he won a golf tournament in Las Cruces in July 1966.34 Thereafter his name appeared on the sports pages with regularity. By the early 1970s, Herb Wimberly, the golf pro and manager of the NMSU golf course, commented that Roy Nakayama was “a winner in just about every tournament he enters.”35 Roy Nakayama was also an accomplished bowler, as was Rose. During the 1970s his name frequently appeared in the newspaper among the bowling league results.36 Nakayama also loved to fish.

Beyond his research and teaching activities, Nakayama was a sportsman. Playing to a fifteen handicap after only a year of serious play, he won a golf tournament in Las Cruces in July 1966.34 Thereafter his name appeared on the sports pages with regularity. By the early 1970s, Herb Wimberly, the golf pro and manager of the NMSU golf course, commented that Roy Nakayama was “a winner in just about every tournament he enters.”35 Roy Nakayama was also an accomplished bowler, as was Rose. During the 1970s his name frequently appeared in the newspaper among the bowling league results.36 Nakayama also loved to fish.

One of Nakayama’s favorite activities was acting as one of the judges at the annual International Chili Society cooking competition. During the 1970s the event was often held at the Tropico Gold Mine near Rosamond, California, where Nakayama joined celebrities from the entertainment and sports world to judge chile cooking and eating contests.37

In 1975, Nakayama released a new chile cultivar called ‘NuMex Big Jim’, which is considered the world’s largest chile, averaging 7.68 inches in length and 1.89 inches in width. It is a little bit hotter than ‘New Mexico 6-4’, but not as hot as ‘Sandia’. Its large pods make ‘NuMex Big Jim’ a favorite of home gardeners and chefs for making chile rellenos.38

In 1977 the Las Cruces Board of Realtors recognized Nakayama as its Citizen of the Year for having “contributed most to the betterment of the community in bringing recognition to the area and my affecting conditions directly related to community improvement.” The realtors pointed out that Nakayama’s release of ‘NuMex Big Jim’ in 1975 received coverage in the New York Times and Time magazine.39 The United States doubled its consumption of chile products between 1974 and 1984. Much of the increase was a result of the release of new varieties by NMSU.40

In 1984, Nakayama and Dr. Frank Matta, superintendent of the NMSU Agricultural Science Center in Alcalde, released a new cultivar they called ‘Española Improved’.41 The new cultivar was a result of a hybridization between Sandia and a Northern New Mexico strain of chile.

It is an early-maturing red chile cultivar (155 days). It was bred for earliness and adapted to the shorter growing season in north-central New Mexico. It produces long, smooth, fleshy fruit with broad shoulders tapering to a sharp point at the apex. This shape is common among native pod shapes in the area. The mature, dark green fruit of ‘Española Improved’ average 6.18 inches in length and 1.23 inches in width. Relatively high green pod yields, fruit size, and marketable characteristics (long, smooth pods) make it superior to native strains for use as green chile. Fruit are also adapted for dry red products; its smooth, well-shaped pod dries well. It has high heat levels.

The new cultivar proved popular in the northeastern United States as well. People were reportedly growing it in pots in New York City apartment windows.42

Nakayama released ‘NuMex R Naky’, named it after his wife, Rose, in 1985. Its pedigree included Rio Grande 21, New Mexico 6-4, Bulgarian paprika, and an early-maturing native New Mexican type of chile. NuMex R Naky is used as a paprika cultivar in New Mexico because of its undetectable or low heat level.[43]

During his long career as an academic, Nakayama’s colleagues and former students noted his dedication to teaching. Even though the outside world knew him as Mr. Chile, Nakayama also dedicated much of his time to research on pecans. He is credited with developing two pecan types, Sullivan and Salopek.44

Dr. Roy M. Nakayama retired from NMSU in 1986. He died in Las Cruces on July 11, 1988 after having been hospitalized for an illness.45 At the time of his death in 1988, Dr. John Mexal, associate professor in the agronomy and horticulture department at NMSU, estimated that Nakayama’s research was responsible for $10 million of New Mexico’s annual income.46

Endnotes

[1] “Member of A&M Staff since Graduation 51 Years Ago, Fabián García is Retired,” Las Cruces Sun-News, April 22, 1945.[2] The census enumerator recorded Fabián as “Fabiano” and mistakenly indicated that he was female, but there is no doubt that the entry refers to him and his grandmother. United States Federal Census, San Lorenzo, Grant County, Territory of New Mexico, 1880; and http://archives.nmsu.edu/rghc/exhibits/garciaexhibit/menu.htm (accessed July 7, 2010).

[3] “Goals at New Mexico A&M High, Writes Noted Author,” Las Cruces Sun-News, March 1, 1949.

[4] Las Cruces Sun-News, October 9, 1949.

[5] http://archives.nmsu.edu/rghc/exhibits/garciaexhibit/menu.htm (accessed July 7, 2010).

[6] “New American Bees,” The Entomologist, vol. 40 (December 1907): 265-66.

[7] Julieta was born in Las Cruces on November 24, 1882. “Julieta Amador García,”The Rio Grande Republic, December 9, 1920.

[8] Rio Grande Republic, May 23, 1908.

[9] Rio Grande Republican, October 17, 1908.

[10] “Cultural Train Starts on Its Long Tour of Instruction,” The Rio Grande Republican, January 12, 1912.

[11] Rio Grande Republican, May 17, 1912.

[12] Rio Grande Farmer, March 27, 1922.

[13] Danise Coon, Eric Votava, and Paul W. Bosland, The Chile Cultivars of New Mexico State University, Research Report 763 (Las Cruces: New Mexico State University, 2008): 1.

[14] Fabián García, Improved Variety No. 9 of Native Chile, Bulletin No. 124, February, New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, Agricultural Experiment Station, State College, N. M. (Las Cruces: Rio Grande Republic, 1921), [3].

[15] “Julieta Amador García,” The Rio Grande Republic, December 9, 1920.

[16] “Member of A&M Staff since Graduation 51 Years Ago, Fabián García is Retired,” Las Cruces Sun-News, April 22, 1945.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Late Fabian Garcia One of Best Loved of A&M Faculty Members,” Las Cruces Sun-News, October 9 and 16, 1949.

[19] “Date is Set for Dedication of Memorial Hall,” Las Cruces Sun-News, July 26, 1949.

[20] David A. Fryxell , “The Red-or-Greening of New Mexico,” http://www.desertexposure.com/200712/200712_garcia_chile.php (accessed July 8, 2010).

[21] United States Federal Census, 1930, San Ysidro, Doña Ana County, New Mexico; and “Roy Minoru Nakayama,” http://www.discovernikkei.org/es/resources/military/15718 (accessed July 12, 2010).

[22] Nancy Tod, “The Deeds of Roy Nakayama: Chile and Pecans; Research and Teaching,” Southern New Mexico Historical Review, vol. 1 (January 1994): 23.

[23] Tome was born on August 9, 1895, and died on October 27, 1990. Social Security Death Index, [Database on-line,] Ancestry.com, (accessed August 19, 2010); Tod, “Deeds of Roy Nakayama,” 24.

[24] Ibid., 25.

[25] Ibid., 22.

[26] El Paso Herald-Post, February 20, 1939.

[27] “500 Future Farmers from 45 Schools Take Over Town and College,” Las Cruces Sun-News, April 12, 1939.

[28] “Vocational Agriculture Students Are to Judge Livestock Saturday,” Las Cruces Sun-News, December 7, 1939.

[29] “15 H. S. Students Get FFA Degrees,” Las Cruces Sun-News, December 14, 1939.

[30] “High School Boys In Stock Contest,” Las Cruces Sun-News, March 25, 1940.

[31] Tod, “Deeds of Roy Nakayama,” 25-26.

[32] Iowa State University Reference Specialist Becky S. Jordan to Rick Hendricks, Ames, August 24, 2010 (email).

[33] New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts changed its name to New Mexico State University in 1960. “State Garden Clubs’ Speakers Specialists-All,” Las Cruces Sun-News, October 7, 1970; Roy Minoru Nakayama, “Seed Treatment of Legumes and Grasses” (Unpublished Master’s thesis, Iowa State College, 1950); Roy Minoru Nakayama,”Verticillium Wilt and Phytophthora Blight of Chile Pepper” (Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Iowa State University, 1960).

[34] Herb Wimberly, “Divot Dust,” Las Cruces Sun-News, July 10, 1966.

[35] Herb Wimberly, “Divot Dust,” Las Cruces Sun-News, May 6, 1971.

[36] “Trujillo Turns 671 Series to Pace City,” Las Cruces Sun-News, December 18, 1972.

[37] “Celebrities Judge Chili Championships,” Las Cruces Sun-News, September 27, 1975; “Chile championship headed for cookoff,” Las Cruces Sun-News, June 3, 1976.

[38] Danise Coon, Eric Votava, and Paul W. Bosland, The Chile Cultivars of New Mexico State University, Research Report 763 (Las Cruces: New Mexico State University, 2008), 3-4.

[39] “Realtors Give Awards,” Las Cruces Sun-News, April 22, 1977.

[40] “Chile time signals fall,” Santa Fe New Mexican, September 13, 1989.

[41] Coon, Votava, and Bosland, Chile Cultivars of New Mexico State University, 4.

[42] “New type of green chile is well-suited to this area,” Santa Fe New Mexican, September 4, 1985.

[43] Coon, Votava, and Bosland, Chile Cultivars of New Mexico State University, 4.

[44] Tod, “Deeds of Roy Nakayama,” 26.

[45] Social Security Death Index, [Database on-line,] Ancestry.com, (accessed August 18, 2010).

[46] “‘Mr. Chile’ dead at 64,” Las Cruces Sun-News, July 12, 1988.

Rick Hendricks is the New Mexico State Historian and a past president of the Historical Society of New Mexico. He has authored or co-authored over a dozen books, including the extensive don Diego de Vargas series. He has contributed to all three volumes of the Sunshine and Shadows in New Mexico’s Past.