Main Bazaar, Delhi |

Recipes:Spiced Fish Egg Balls

|

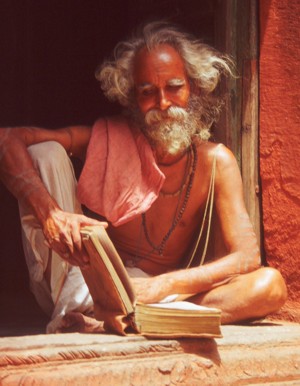

With unusual furtiveness and haste, Sanghamitra moved towards the door as she announced that she was going to the West Bengal market round the corner. Earlier I had told her I wanted to join her, and she had said there was no need to. Now I asked her to give me a minute to fetch my flip-flops. She frowned and hesitated, then said, “It’s dirty, you will not like it.”

So she wanted to keep me away from the aspects of India that ashamed her, the things she didn’t want a foreigner to see, such as the chaos and filth of fresh markets in Indian cities. But these things no longer repulsed me as they had in the first month. That morning, the concrete floor of the West Bengal market was splattered with blood emanating from the fish stands where fishes were cleaned and chopped, and the throaty bellowing coming from all stalls at once was unnervingly insistent. But I noticed these things only from the periphery of my senses, because my mind was scanning the variety of ingredients stacked all around–there was so much I didn’t recognize.

A bond of mutual interest had quickly developed. I was the first Westerner they had had in the house; they were the first Indian family I had lived with. Moreover, since Indian men never ventured into the kitchen, considering cooking and cleaning the sole domain of women, my interest in cooking had made an impression. My presence in the kitchen–helping with cooking, taking notes–became a point of discussion with friends and relatives. People would laugh when they heard, and the maid, who did the washing and chopped the vegetables, was always chuckling at my eccentricity–the man who liked to cook.

Sanghamitra and I typically spent three hours in the kitchen every morning preparing the four or five dishes that were recycled for lunch and dinner. A fish dish would always be featured, as would a dal as a base sauce that can complement any other sauce, and sometimes meat dishes such as chicken curry or chicken biryani, accompanied by a daily-changing concoction of simple vegetable dishes. Dishes would mostly be eaten with chapatti–flat bread torn and used to scoop sauce–and, more rarely, rice. Everything was eaten with the right hand, but it took me some days before I learned how to eat using my hand without spattering sauce all over, the sauce drizzling down my arm and dripping off my elbow–another comical occasion for my hosts. Yet this was the least of my preoccupations (and forks were available for people like me), because I had more important things to learn: the tenets of West Bengal cooking, which is arguably the most varied and creative cuisine in the whole Indian subcontinent.

“In West Bengal,” Sanghmitra explained one day, “we eat everything–all the parts of a banana tree, jackfruit seeds, peels of vegetables, shells of shrimps–everything that lives, and nothing is discarded. We cook mutton in fifty different ways, while North Indians only have four or five dishes with mutton. We cook mutton without onions, which is unthinkable in North India, for example.”

Pastes featured heavily in Sanghamitra’s kitchen. One of her favorites was a mustard paste, with mustard seeds, green chiles, turmeric, and water, crushed or ground in a mortar. The standard paste, which she kept in the fridge, was made of blended onion, chile, ginger, and garlic–it is this paste, as well as liberal use of oil and long cooking times, that gives Indian curries their creamy consistency. In West Bengal, only mustard oil is used, and the most used spices, aside from turmeric that went in virtually everything, were ground coriander and cumin; less common spices were bay leaves, fenugreek, mustard seeds, coriander seeds, and masalas (for fish, meat, and chicken).

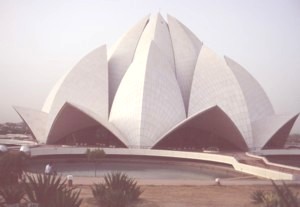

I did everything with the family. I went to the local Hindu temple–it had been designed by Subash, an architect–to make offerings. I went shopping with Sanghamitra every day. Sanghamitra was especially fond of me because I took an interest in India, and I liked India, and this was contrary, she said, to many Westerners she had heard about who thought India was backwards and who didn’t like to mix with normal Indians.

Sanghamitra then wanted me to do a Mediterranean meal. I made pasta with a simple sauce–fried onions, then chopped tomatoes and black eyed peas spiced with cumin and cinnamon–followed by the classic fish in the oven (baked in olive oil, lemon, garlic, and white wine) accompanied by sautéed chopped potatoes. They loved the fish and potatoes, but the pasta was a puzzle. I served the sauce on top of the pasta, and all of them ate the part of the pasta that was covered by the sauce but left the rest, a band of pasta around the rim of the plate–and asked for more sauce. But I had served all the sauce already. Then I realized my folly: Italian pasta is served three parts pasta to one part sauce, but in Indian cooking, it’s one part sauce to one part rice. I explained this to them. Sanghamitra said, “More sauce next time! It’s the sauce that gives taste.”

Deep-Fried and Spiced Fish Egg Balls

Any fish can be used for the fish-eggs, but West Bengalis like to use only freshwater fish. The quantity of flour depends on how much it takes to make non-breakable balls. The egg is both for binding and to deepen the taste–half an egg is enough, but you could use more or less if needed.

Knead all ingredients except the oil until well-mixed and the resultant mix achieves sufficient consistency to stick together. Then form small balls from the mixture, heat the oil in a heavy skillet until medium hot but not smoking, and fry the balls on medium heat for 2 minutes, or until starting to turn golden.

Yield: 10 balls

Heat Scale: Medium

Photo: Norman Johnson

If you can’t find bottle gourds, substitute potatoes, or potatoes and cauliflower: either two cups chopped potatoes, or one cup each of potato and cauliflower. In the event that these substitutes are used, cook in the same way as the bottle gourds, i.e., fry separately until cooked.

In a skillet, over medium heat, fry the bottle gourds until soft and put aside. Add more oil and return the skillet to heat, then fry half the potatoes in fenugreek, fennel, and cumin and mustard seeds for a few minutes, until the potatoes are half cooked. Then add the bottle gourds to the dish, and cook for another minute on medium heat; add some water until the vegetables are just covered, turn down the heat, and let simmer until the potatoes are cooked.

In a separate skillet, add mustard oil and when hot put in bay leaves, cloves, cardamom, and cinnamon stick for a minute; then add the rest of the potatoes and continue frying, stirring constantly, for about three minutes. Next add the blended onion and ginger, a little more turmeric, chile powder, and fry over low heat until the potatoes are cooked. Increase heat, toss in all ingredients, including the prawns and coconut milk, and simmer for a few minutes until the prawns are cooked.

Yield: 4 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Indian curries are best if you don’t mind your oil intake! It is the addition of lots of oil–up to 4 tablespoonfuls–that gives the sauce a creamy consistency and intensity. Regardless of how much oil you use, you have to keep stirring the onion or it will scorch, and it’s the same with the sauce when it is simmering–stir it every ten minutes at least. West Bengalis like to use fresh-water fish. You can use any white fish that has firm meat (I have tried it with different salt water fish, and it worked well each time); the fish is initially fried in turmeric specifically to counterbalance the fishy taste.

Rub turmeric on the fish, adding more turmeric if necessary. Heat some mustard oil in a skillet until it starts smoking, and fry fish pieces on high heat for about three minutes on each side, or until almost cooked. Put fish aside, and in the same skillet fry cumin seeds, bay leaves, red chiles, garlic, onion, some more turmeric, and cook on medium heat, stirring, for a few minutes; then add potatoes and continue frying until half-cooked. Then add the chopped tomatoes and ground chile and water and sugar, cover, and simmer for about 30 minutes, or until the sauce is reduced to a creamy consistency. Add fish and simmer for a further 15 minutes.

If using lemon and yoghurt, mix into the sauce just before serving.

Yield: 4 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Whole Fish in Mustard Sauce

The fish have to be small–not longer than a pen–and thin, not wider than one inch. Small breams, particularly saddled breams, work well with this dish. But this is a salt-water fish, and West Bengalis prefer, where possible, to use only fresh water fish. Mustard sauce is made from grinding mustard seeds, red chiles, and turmeric (plus optional ginger and coriander seeds) –use one red chile for one tablespoon of mustard seeds and one teaspoon of ginger and coriander seeds–and add water until you achieve a creamy, but non runny, consistency.

Sprinkle the fish with turmeric, and fry in mustard oil in a frying pan on medium heat until cooked. Put aside.

In the same pan, fry the seeds and garlic and chile for a minute or two on medium heat. Then lower the heat, add mustard paste, a little water, and simmer until the sauce thickens to your liking. Then toss in the fish and yoghurt (purpose of yoghurt is to balance the tang of mustard seeds) and serve.

Fish in Tamarind Paste

For tamarind paste, buy commercial ready-made paste. Use any white fish that has firm meat.

Rub turmeric into the fish pieces, adding more turmeric if necessary, and fry in a skillet on medium heat in mustard oil until almost cooked. Put aside.

In the same skillet, fry the green chiles a bit, then add the remaining ingredients, reduce heat, and simmer until thickened for about 10 minutes. Put in the fish, simmer for another ten minutes until sauce is thickened but still runny (add more water if necessary), then serve.