In order to unlock the history and mystery surrounding the origins of the chile peppers, a genetic comparison needs to be made between domesticated and wild chile peppers. While there are plenty of domesticated peppers available, there were previously no collections of wild chile peppers for use in this type of analysis. So, before I could begin the laboratory work of genotyping these peppers, I needed to head to Mexico to collect the wild peppers myself. Armed with a map, a great collaborator in Mexico, and half a plan, my wife, Heather, and I set off south of the border on a 10,000-mile chiltepín crusade. While the majority of the readers of this magazine would think of this as an odd, but reasonable pursuit, this trip was strictly business; we took the hunt for chiltepín very seriously!

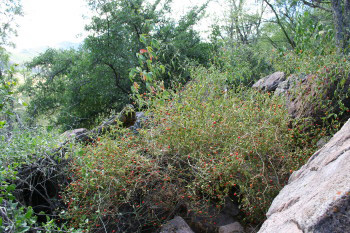

The goal was to collect fruits, seeds and GPS coordinates from as many individual chiltepín plants as we could. Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum is thought to have a range that goes from Arizona down to Columbia, often taking on different local names (chilpete, chile piquin, chilpiquin, chile conguito). While I didn’t have the time to go that far, I did need to make sure that we covered as much ground as we could during these weeks while the fruits were still ripe on the plant. Before our departure, I had targeted two known and characterized populations as a start: the Tumacacori Mountains of Arizona, and the Rio Sonora Valley in Mexico. After these, we would have to depend on local contacts, my Mexican collaborator in Aguascalientes, and word of mouth to find other chiltepín locations.

Yellow chiltepín

During the process of domestication, plants undergo changes in certain traits that make them more amenable to humans and agriculture such as larger seeds, larger fruits, a compact growth habit, and so on. Selection for this suite of traits leaves a mark on the plant’s genome by the reduction of genetic diversity in the areas that code for these traits. This process is called the domestication syndrome. Through comparing the genetic diversity of wild and domesticated chile pepper, I can find the fingerprints of the domestication syndrome and trace back the origins of chile pepper.

This is exactly what happened in our next stop. We headed south towards Alamos–only because I had read the name in collection accounts of wild chiltepíns and because a contact in Hermosillo mentioned that they remembered a small shop run by the Hurtado family that sold chiltepín and cajeta, local sweets made of milk or fruit and tons of sugar. They were the best lead we had. Upon arriving in town, we parked the truck and started to canvas the local cajeta establishments. After surveying the local competition, we had tracked down Horacio Hurtado, whose fiery personality matched that of the object of our pursuit. Horacio thought that we were the craziest gringos he had seen in a while, but he would love to help us in our search. Not knowing where the chiltepín plants were, he sent us back up his supply chain in order to track them down. We drove two hours north of Alamos on a dusty one lane road to the town of San Bernardo. We found his supplier, whose day job was to manage the local Tecate distribution center. He was a middleman himself, and did not know where the plants were. Spotting his elderly neighbor, he put him into our pickup to lead our search. The elderly gentleman quickly guided us to three plants that were on the outskirts of town, but he seemed reluctant to lead us any further, saying that the rest of chiltepín were “mas alla, todavia” (still further)–a common answer we heard when we asked about the location of the plants. A bit disappointed, we began to drive back to Alamos when we happened upon a small governmental office, the National Commission for the Development of the Indigenous Peoples. On a whim, we stopped and explained our story. Talk about luck – they provided us with a guide, their doctor wanted to have us over for lunch to talk about politics and our careers and research (my wife works in public health) and we saw a chiltepín nursery project which was constructed to generate some income. All of this set off in motion by the mention of a small business in Alamos that sells chiltepín as a minor product.

There is a great demand for these peppers, a demand that can exact its toll on the wild populations. Some careless harvesters would take down entire branches, even cutting down the plant first to then harvest the fruit. In other locations the chiltepín habitat is lost as it is plowed under for tomato fields or for housing developments. For many in Sonora, collecting chiltepíns is an important economic activity, supplementing subsistence activities. Luis said that if the rains came then there would be plenty of chiltepín to harvest and some money to pocket and save at the end of the year. The chiltepín is not just the primordial pepper but also an integral part of the social, cultural, and economic fabric and an incredibly addictive spice in its own right. When speaking with people about the chiltepín, we would often hear a popular Mexican saying, or dicho: “Si no pica, no sabe“–literally, if it doesn’t have any spice, it has no taste. With heat registering from 50,000 to 100,000 Scoville Heat Units, the chiltepín is definitely not short on spice.

For your own chiltepíns, Native Seeds/SEARCH has some for sale on their website, www.nativeseeds.org

Chiltepín Michelada

A michelada is a type of Mexican beer cocktail that has definite regional variations, just like many other types of Mexican food. Using chiltepín as the heat source gives the drink a nice Sonoran kick. This is really refreshing on a hot day!

1 cup Clamato or tomato juice

1 lime, quartered

Dash Worchestershire sauce

1 chiltepín pepper, ground up with your fingers

1 bottle of Mexican beer (everyone has their favorite–I like Negra Modelo or Indio)

Salt for rim of the glass

Ice (optional)

Take a pint glass and moisten the rim with one of the lime quarters. Rim the glass with salt by inverting the glass onto a plate with salt. Add ice to the glass if you would like (Mexicans drink it with ice, but Americans don’t like the idea of ice in beer). Add the Clamato, Worchestershire sauce, and ground up chiltepín. Pour the beer into the glass (you will have beer remaining) and squeeze a lime wedge into the concoction. Serve immediately and enjoy!

Yield: 1 serving