|

|

Recipes: Chile Verde con Carne Chile Colorado Carne Adovada Posole with Chile Caribe Calabacitas with Green Chile

|

Any museum curator worth his weight in Roman coins would choke at the thought of throwing away a 400-year-old artifact.

Yet one of America’s most precious pieces of heritage is at risk of vanishing off the face of the Earth. In the mountain valleys

of northern New Mexico, direct descendants from some of the first chile peppers brought to the United States are amazingly

still alive. The crops emerge from the ground like a perfectly preserved Pompeii. But they are starting to die out.

|

|

Heirloom fresh red chiles. Photo by Dave DeWitt

|

It has taken a long time for the economy and modern technology to nudge the native New Mexico chile pepper out of existence, but it’s finally happening. Farming on these small, family-owned Hispanic estates is fiercely competitive. When the siren calls, offering high-yield hybrids or cold cash for land, it’s difficult for anyone to resist. Even those who would no sooner give up their local chiles than a coat of arms are having trouble keeping crops pure. Given that chile peppers ranging from jalapeños to cayennes dominate the New Mexico landscape, a few floating grains of pollen from another crop can irreparably change the integrity of a heritage chile.

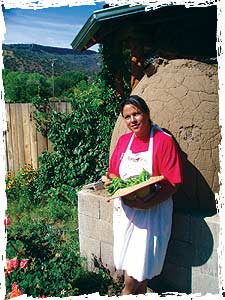

“The only way farmers in northern New Mexico can survive is if they are willing to live below the poverty level or diversify their income,” says Margaret Campos, who owns the Algo Nativo organic chile farm in Embudo, New Mexico. She has “diversified” by opening the Comida de Campos cooking school, which offers chile-roasting classes in August and September.

“It’s hard to compete with California and Mexico, when they have longer and multiple growing seasons, established infrastructure for delivery, and an organized labor force. Thank God for farmers’ markets,” she says.

|

|

Margaret Campos holds some of her Photo by Lois Lyles

|

Campos’s family is typical in that they’ve been farming the land there for more than half a century, although the native New Mexico peppers they produce far outdate them. Farmers have been growing the same chile crops there at least since the early 1600s and possibly earlier. Santa Fe, one of the oldest cities in the United States, is at a crossroads of major trade routes, kind of an American Spice Road. The Old Santa Fe Trail, the Old Pecos Trail and the Camino Real converge here, and consequently an international jumble of seeds, plants, and foods. Chile peppers made their way into the area through trade with Mexican tribes, maybe as early as 1582 on a Mexican expedition lead by Antonio Espejo. One of the members Baltazar Obegon wrote, “They have no chile, but the natives were given some seed to plant.”

|

|

The perfect rows of Margaret Campos’ chiles.

|

The peppers were certainly in New Mexico with the arrival of conquistador Don Juan de Oñate, who breezed into Santa Fe in 1598 with a sack full of seeds and changed the landscape forever, according to Eric Votava, a senior research specialist at the New Mexico State University Chile Pepper Breeding Program.

“We recently completed a study at NMSU in which we looked at the DNA of landraces from northern New Mexico and compared them to modern cultivars and landraces collected from Mexico,” he says. A “landrace” refers to an historic chile that has grown in the same place for many years. “We found that the landraces from northern New Mexico were genetically unique, and that they were genetically more similar to landraces from Mexico than they were to modern cultivars. These landraces are the direct descendants of chile brought to New Mexico from Mexico. In essence they are a living link to 400 years of New Mexico history.”

This, says Votava, is what gives native New Mexico chiles such a singular flavor. After so many years of dedicated cultivation, the chiles in the region have developed particular characteristics based on anything from the amount of sand in the soil to how much water flows to their roots. These native strains, or landraces, taste different depending on if they’re grown in Chimayó or a few miles down the road in neighboring Dixon or Española. The locals each have their favorites but unanimously agree that they taste better than commercial crops grown for standardization over flavor.

|

|

‘Chimayó’ type chile. Photo by Dave DeWitt

|

The land is as important to the chiles as the chiles are to the locals. To say New Mexico owes its financial livelihood and cultural heritage to the chile pepper would be like saying a habanero is slightly piquant. The chile pepper is to New Mexico as wine is to France. New Mexico is the leading U.S. state in pungent chile production, and the three counties Doña Ana, Luna and Hidalgo alone generate $418 million annually in economic activity. Chiles are everywhere, draped over doorways, piled up at farmers markets—even the university rugby team is called the Chiles.

|

|

‘Española Improved’. Photo by Dave DeWitt

|

Needless to say, everyone eats them. “Indigenous families never have a meal without some kind of chile on the table: green, red, salsa or ha mordidas (fresh chile to bite on),” says Campos.

The fact that chile peppers are so important to New Mexicans is part of what’s endangering the native New Mexico chiles. They might be a delicious part of everyday life, but they’re not commercial blockbusters. The native chiles look distinctly unlike their plump and regular relatives to the south. They’re about five inches long, usually twisted and have irregular heat, although Campos says hot and dry summers usually mean hotter chiles. They also have thin walls, unlike the thick meaty wall of a big Jim, which makes the lye wash used for peeling almost impossible (they disintegrate). Likewise, commercial propane roasters turn them into cinders.

Back at the turn of the 20th century, Fabian Garcia, a pioneer horticulturist at New Mexico State University, realized the problems inherent with native landraces and introduced both the savior and ruin of the chile pepper industry: ‘New Mexico No. 9′.

This cultivar was a farmer’s dream, with its regular size and shape and dependable heat. It was a commercial success and kicked-off the Mexican food boom in America. Farmers, in particular in southern New Mexico where the growing season is longer, eagerly swapped out their traditional landraces for the new cultivar and started turning out profitable crops. On the other hand, the landraces that exited there have vanished and been replaced by more commercially viable options.

The same could happen to northern New Mexico’s native chiles, says Votava. “Plus, if the local landraces aren’t replaced outright, they may cross pollinate with modern varieties, thus changing their genetic structure and the very nature of these landraces.”

“It’s a constant problem,” agrees Campos, “but most small growers are aware for the need to keep their stand separate and guard their seed like gold.” Farmers must be scrupulous about segregating their own crops and steering clear of each other at markets.

Unfortunately, she adds, “Since there aren’t that many folks growing anymore, you typically don’t have to worry about what your neighbors are doing.”

The principle reason the neighbors don’t pose much of a threat is because they don’t know the first thing about farming. These chiles grow in beautiful country. So beautiful, in fact, that non-agricultural families are offering large sums of money for land with gorgeous vistas and rights to New Mexico’s precious water resources. Struggling farmers have a hard time turning from that kind of deal.

“Another major issue is that individuals who run into hard times might be seduced into selling the water rights away from the land, leaving behind land that can never again be farmed,” says Campos.

Caught in a Milagro Beanfield War-type battle, farmers, locals, and foodies who love the chiles are asking themselves, “How will the native New Mexico survive?”

The Slow Food Movement, which is to food as Greenpeace is to natural resources, hopes it can help by making sure the little-known chile is receiving the attention it deserves. Deborah Madison, who leads the local branch of the movement and wrote the James Beard Award-winning book Local Flavors: Cooking and Eating from America’s Farmers’ Markets, nominated the native New Mexico chile to be protected by Slow Food.

“The idea is to bring attention to it, so that it is recognized as a food that has value,” she says. Even if the northern New Mexico crops will never feed the world—which, given the landrace’s limited growing areas, they never will—Madison hopes as people become aware of the chile it will help northern New Mexico’s other cultural and environmental issues.

Campos gives one resounding reason that the northern New Mexico natives will survive, even if they do dwindle to single-serving portions: “Flavor, flavor, and more flavor.”

Simply stated, people who’ve tasted the northern New Mexico native say they win any taste test, hands down. The various chiles might all be different, but they’ve been around for so long developing a rich and sweet flavor that they’ll always remain, at least to locals, history’s most heavenly taste.

|

The New Mexico Landrace Question by Dave DeWitt What Is a Landrace? According to chile breeder Dr. Paul Bosland of New Mexico State University, a landrace is a variety of chile that has been grown for many generations (and in some cases, hundreds of years) in the same location, and has adapted to that location. Some examples of landraces are ‘Datil’ and ‘Florida Grove’ in Florida and ‘Chimayó’ in New Mexico. They are open-pollinated, which means that they will cross-breed with any other variety of Capsicum annuum. This has led to problems in preserving the genetic identity of the landraces. The carefully bred cultivated varieties, or “cultivars,” will cross pollinate with the landraces if they are grown closely together. The following year’s crop will produce some hybrids, which are discernible by extensive pod variation in shape and size on the same plant. What Are the New Mexican Landraces? The New Mexican landraces were developed from seeds brought from central Mexico by the early Spanish explorers who settled towns such as San Juan and Santa Fe in northern New Mexico after 1600. The best-known landrace is ‘Chimayó’, which may be the ancestor of many of the other landraces. Not much ‘Chimayó’ chile is grown these days–certainly not enough to produce all the bags of red powder labeled as such. As with “Hatch Chile,” ‘Chimayó’ has become a near mythical brand. Unscrupulous sellers label bags of fresh chile as “Hatch” and bags of red powder as “Chimayó,” and very often, this is false advertising. I have compiled a list of possible New Mexican landraces from various sources, but I caution that because of cross-breeding, some seeds you receive may be unintentionally hybridized.

And Where Can You Find Them? Many conscientious growers have been preserving landrace seeds and growing them out each year for seed increases. The following organizations are suppliers of seeds and plants of New Mexican landraces. Native Seeds/SEARCH. This Arizona organization for preserving Southwestern plants supplies seeds to consumers for many of the landraces, particularly those grown on Indian pueblo lands. Visit them at www.nativeseeds.org Seed Savers Exchange. Collectors and seed savers join this Iowa organization to trade heirloom seeds. You will need to join to receive their complete catalog, which has hundreds and hundreds of chile varieties, including some landraces. Visit them at www.seedsavers.org Cross Country Nurseries. This company carries more than 500 varieties of live chile plants in season, including ‘Chimayó’. You will need to search their database to see if they carry any other landraces. Visit them at www.chileplants.com |

Recipes

Margaret Campos, who owns an organic chile farm and the Comida de Campos cooking school in Embudo, New Mexico, provided this recipe. Since the native chiles in northern New Mexico vary from one micro-region to the next, Campos says to use whatever you have on hand. She serves this green chile stew alone or with beans and a fresh tortilla.

-

15 medium-sized (5- to 7-inch) chiles

-

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon lard

-

1 pound pork shoulder, trimmed and cut into ½-inch cubes

-

2 tablespoons flour

-

2 garlic cloves, pressed or chopped

-

3 cups stock or broth

Over a medium-hot grill or in a 350 degree F oven, roast the chiles until the skin begins to bubble. Rotate the chiles to roast them evenly—be diligent to avoid scorching. Chiles will change color when they’re done; the green acquires a yellow hue. Place the roasted chiles in a bowl and cover with a damp cloth and allow them to steam and cool. When the chiles are cool enough to handle, remove the skin, stem and seeds (seeds are optional). Chop the chiles and set aside.

In a medium-sized skillet, add 1 tablespoon lard, and brown the pork over medium-high heat, approximately 10 to 12 minutes. When the pork is done, add the remaining lard and flour, stirring and cooking for two minutes. Brown the flour slightly, and add the garlic. Mix in the chile and stock, and combine well. Lower the heat and allow to simmer 10 to 15 minutes until the broth has thickened, stirring frequently. Simmering longer will bring out the heat in chile, so simmer to taste. If your chile is too spicy, add diced tomato or a tablespoon of milk to cut the heat.

Yield: 4 main dish servings or 10 to 12 as a condiment

Heat Scale: Hot

|

|

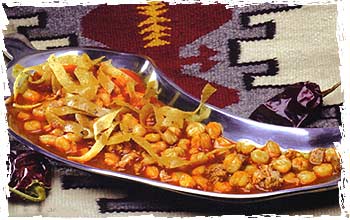

Chile Colorado Enchiladas with Calabacitas. Photo by Norman Johnson

|

This red chile is wonderful on its own served with beans or layered with corn tortillas, cheese and onions to make enchiladas. Margaret Campos also serves it at breakfast to spice up fried eggs.

-

1 pound pork shoulder, trimmed and rinsed

-

4 to 5 garlic cloves, crushed and divided

-

1 teaspoon salt

-

1 quart water

-

2 tablespoons bacon drippings or cooking oil

-

1 tablespoon flour

-

½ cup red chile powder (Chimayó preferred)

Rub the pork with 2 garlic cloves and the salt. Place in a slow cooker with the water. Set to cook for 6 hours, or alternatively cook in a pressure cooker for 30 minutes. Cool the meat, removing any excess fat, and shred. Set aside the broth.

Over medium heat in a 2-quart skillet, heat the bacon drippings or oil and add the flour, stirring to cook for two minutes. Add in the remaining garlic and shredded pork, browning lightly. Mix in the powdered chile, incorporating thoroughly into the meat mixture. Brown ever so slightly, being careful not to scorch the chile powder. Add broth slowly to completely dissolve any chile, lower heat to lowest setting and let it simmer until the broth thickens.

Yield: 4 main dish servings or 10 to 12 as a condiment

Heat Scale: Hot

This simple but tasty dish evolved from the need to preserve meat without refrigeration since chile acts as an antioxidant and prevents the meat from spoiling. It is a very common restaurant entree in New Mexico. Note: This recipe requires advance preparation.

-

1½ cups crushed dried red New Mexican chile, seeds included (Chimayó preferred)

-

4 cloves garlic, minced

-

3 teaspoons dried oregano

-

3 cups water

-

2 pounds pork, cut in strips or cubed

Combine the chile, garlic, oregano, and the water and mix well to make a “caribe” sauce.

Place the pork in a glass pan and cover with the chile caribe sauce. Marinate the pork overnight in the refrigerator.

Bake the marinated pork, uncovered, in a 300 degree oven for 2 hours or until the pork is very tender and starts to fall apart. You may have to add a little water to keep the pork from burning.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Hot

Serving Suggestions: Place the Carne Adovada in a flour tortilla to make a burrito, use it as a stuffing for sopaipillas, or use it as filling for enchiladas. If you add chopped potatoes during the last hour of baking, the dish becomes a sort of stew.

|

|

Posole with Chile Caribe. Photo by Norman Johnson

|

Posole is corn that has been treated with lime to remove the outer shell of the kernel. In the South, it’s called hominy corn. Here is the classic version of Southwestern posole as prepared in northern New Mexico.

The Posole:

-

2 dried red New Mexican chiles, stems and seeds removed (Chimayó preferred)

-

8 ounces frozen posole corn or dry posole corn that has been soaked in water overnight

-

1 teaspoon garlic powder

-

1 medium onion, chopped

-

6 cups water

-

1 pound pork loin, cut in ½-inch cubes

Combine all the ingredients in a large pot except the pork and boil at medium heat for about 3 hours or until the posole is tender, adding more water if necessary.

Add the pork and continue cooking for ½ hour, or until the pork is tender but not falling apart. The result should resemble a soup more than a stew.

The Chile Caribe:

-

6 dried red New Mexican chiles, stems and seeds removed (Chimayó preferred)

-

1 teaspoon garlic powder

In a large pot, boil the chile pods in two quarts of water for 15 minutes. Remove the pods, combine with the garlic powder, and puree in a blender. Transfer to a serving bowl and allow to cool.

Note: For really hot chile caribe, add dried red chile piquins, cayenne chiles, or chiles de arbol to the New Mexican pods.

The posole should be served in soup bowls accompanied by warm flour tortillas. Three bowls of garnishes should be provided: the chile caribe, freshly minced cilantro, and freshly chopped onion. Each guest can then adjust the pungency of the posole according to individual taste.

Yield : 4 servings

Heat Scale: Medium, but varies according to the amount of chile caribe added.

This recipe combines two other Native American crops, squash and corn, with chile. One of the most popular dishes in New Mexico, it is also so colorful that it goes well with a variety of foods.

-

3 zucchini squash, cubed

-

½ cup chopped onion

-

4 tablespoons butter or margarine

-

½ cup chopped green New Mexican chile, roasted, peeled, stems removed (Chimayó preferred)

-

2 cups cooked whole kernel corn

-

1 cup milk

-

½ cup grated Monterey Jack cheese

Saute the squash and onion in the butter until the squash is tender.

Add the chile, corn, and milk. Simmer the mixture for 15 to 20 minutes to blend the flavors. Add the cheese and heat until the cheese is melted.

Yield: 4 to 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium