By Dave DeWitt and Nancy Gerlach

Food Photos by Norman Johnson; Chile Basket Photo by Harald Zoschke; Food Styling by Denice Skrepcinski

|

|

|

Recipes: Chile Pasado (Dried Green Chile) Marinated Rajas New Mexico Green Chile Sauce Green Chile Con Queso Chiles Rellenos with Corn Green Chile Pesto Tomatillo-Chicken Enchiladas Red Chile Pilaf |

One of our favorite destinations in late summer or early fall is southern New Mexico, where more chiles are grown than in all other states combined. It’s chilehead heaven in three distinct growing areas centered around Las Cruces, Deming, and Roswell, but most of the chile attractions are centered in Las Cruces and Doña Ana County, so that will be our focus here.

The Early Days

According to many accounts, chile peppers were introduced into what is now the U.S. by Capitain General Juan de Oñate, the founder of Santa Fe in 1598. However, they may have been introduced to the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico by the Antonio Espejo expedition of 1582-83. According to one of the members of the expedition, Baltasar Obregón, “They have no chile, but the natives were given some seed to plant.” By 1601, chiles were not on the list of Indian crops, according to colonist Francisco de Valverde, who also complained that mice were a pest who ate chile pods off the plants in the field.

After the Spanish began settlement, the cultivation of chile peppers exploded, and soon they were grown all over New Mexico. It is likely that many different varieties were cultivated, including early forms of jalapeños, serranos, anchos, and pasillas. But one variety that adapted particularly well to New Mexico was a long green chile that turned red in the fall. Formerly called ‘Anaheim’ because of its transfer to the more settled California around 1900, the New Mexican chiles were cultivated for hundreds of years in the region with such dedication that several distinct varieties developed. These varieties, or “land races,” called ‘Chimayó’ and ‘Española,’ had adapted to particular environments and are still planted today in the same fields they were grown in centuries ago; they constitute a small but distinct part of the tons of pods produced each year in New Mexico.

In 1846, William Emory, Chief Engineer of the Army’s Topographic Unit, was surveying the New Mexico landscape and its customs. He described a meal eaten by people in Bernalillo, just north of Albuquerque: “Roast chicken, stuffed with onions; then mutton, boiled with onions; then followed various other dishes, all dressed with the everlasting onion; and the whole terminated by chile, the glory of New Mexico.”

Emory went on to relate his experience with chiles: “Chile the Mexicans consider the chef-d’oeuvre of the cuisine, and seem really to revel in it; but the first mouthful brought the tears trickling down my cheeks, very much to the amusement of the spectators with their leather-lined throats. It was red pepper, stuffed with minced meat.”

A Hot History of Chile Improvement

In 1888, the founding of the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts ushered in a new era for the Las Cruces area. The college, which later became New Mexico State University, with the world’s largest campus (6,250 acres), not only assisted in bringing Las Cruces into the modern age by educating the youth of New Mexico, but its researchers also assisted local growers with the latest techniques in horticultural science.

The most immediate problem was chile peppers. There was no control at all over what seeds were planted, so farmers could never predict how large the pods would be—or how hot. The demand for chiles was increasing as the population of the state did, so it was time for modern horticulture to take over.

In 1907, Fabian Garcia, a horticulturist at the Agricultural Experiment Station at the College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts, began his first experiments in breeding more standardized chile varieties, and, in 1908, published “Chile Culture,” the first chile bulletin from the Agricultural Experiment Station. In 1913, Garcia became director of the Experiment Station and expanded his breeding program.

Finally, in 1917, after ten years of experiments with various strains of pasilla chiles, Garcia released New Mexico No. 9, the first attempt to grow chiles with a dependable pod size and heat level. The No. 9 variety became the chile standard in New Mexico until 1950, when Roy Harper, another horticulturist, released New Mexico No. 6, a variety which matured earlier, produced higher yields, was wilt resistant, and was less pungent than No. 9.

The New Mexico No. 6 variety was by far the biggest breakthrough in the chile breeding program. According to the late Dr. Roy Nakayama, who succeeded Harper as director of the New Mexico Agricultural Experiment Sta-tion, “The No. 6 variety changed the image of chile from a ball of fire that sent consumers rushing to the water jug to that of a multi-purpose vegetable with a pleasing flavor. Commercial production and marketing, especially of green chiles and sauces, have been growing steadily since people around the world have discovered the delicious taste of chile without the overpowering pungency.”

In 1957, the New Mexico No. 6 variety was modified, made less pungent again, and the new variety was called “New Mexico No. 6-4.” The No. 6-4 variety became the chile industry standard in New Mexico and over thirty years later was still the most popular chile commercially grown in the state. Other chile varieties, such as Big Jim (popular with home gardeners) and New Mexico R-Naky, have been developed, but became popular only with home gardeners.

These days, Dr. Paul Bosland, who took over the chile breeding program from Dr. Nakayama, is developing new varieties that are resistant to chile wilt, a fungal disease which can devastate fields. He has also created varieties to produce brown, orange, and yellow ristras for the home decoration market. He is assisted by the Chile Task Force, which helps growers improve their cultivation techniques and harvesting techniques to improve yields. The breeding and development of new chile varieties—in addition to research into wild species, post-harvest packaging, cultivation improvement and genetics—are ongoing, ma-jor projects at New Mexico State University.

Today’s Chile Crop

When we think of New Mexico chile, we usually have an image of the long green pods that turn red—the New Mexican varieties. But the crop is much more diverse than just those chiles. Here are the main types of chile grown in southern New Mexico.

Green Chile is sold as fresh to the consumer, dehydrated for spice mixes, or wet processed (canned, frozen, or pickled). Some of this chile undergoes additional processing into salsas, sauces, and such prepared products as enchiladas, chiles rellenos, and tamales.

Cayenne has two primary uses: it is made into mash or dehydrated for powders. Mash is made by crushing the pods in a hammer mill and mixing the resulting paste with salt and vinegar. It is then aged in large storage tanks and moved out of state by truck or rail where it is made into Cajun-style hot sauces.

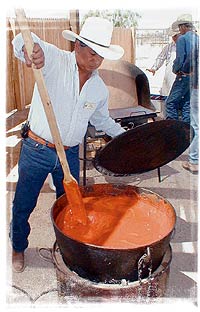

Making Red Chile Sauce

Making Red Chile Sauce

Red Chile is divided into two separate categories: red chile and paprika. Red chile, which is pungent, is left whole to be made into decorative ristras or sold in bags, is crushed into flakes, or is ground into powder. It is further processed into red chile sauces for use in enchiladas, chile con carne, and tamales. Paprika, which has little

or no heat, has two primary uses: the pods are ground into powder or processed for oleoresin extraction. The oleoresin is a natural food coloring that provides the color for barbecue sauce, prepared meats, and potato chips, to name just a few of its uses.

Jalapeños, like green chiles, are sold fresh to the consumer, wet processed, or dehydrated. Most of the crop is either pickled or canned and used in prepared salsas and nachos. When dehydrated, they are used in spice mixes and prepared foods.

Processing the chiles is a big business in New Mexico. Approximately 112,000 wet tons of green chile, cayenne, and jalapeños are processed each year and about 37,000 dry tons of red chile. Total acreage of chiles varies from year to year but averages about 20,000. There are other chiles grown as well, such as piquins and habaneros, but they are a very minor part of the total crop.

Destinations and Celebrations

The Chile Trail

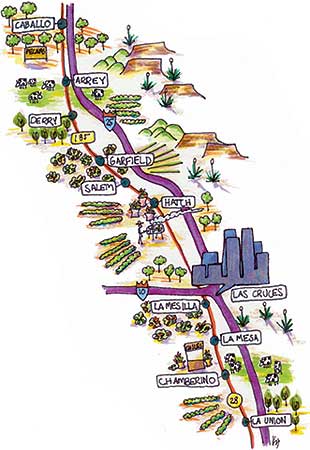

Old Highway 185 begins just south of Caballo, winds though the prime agricultural area of New Mexico and groves of pecans and fields of chiles, alfalfa, pecans, onions, and cotton and the towns of Arrey, Derry, Garfield, Salem, and Hatch, and finally ends up in Las Cruces. There you can pick up Highway 28 and find more agriculture in La Mesilla, La Mesa, Chamberino, and La Union. During the winter, of course, you will see only fallow fields (except for some onions or lettuce), but in the summer months there are thousands of acres planted in chile and other crops. During chile harvesting (late July-September for green), there are teams of pickers roaming through the fields carrying buckets full of green chiles, which are then dumped into large, wooden-sided carts. The jalapeños and red chiles are now mostly mechanically harvested. Photogra-phy is permitted from a distance, but do not trespass, interfere with the pickers, or take any chiles yourself. The pungent pods are available by the bushel from roadside stands.

Chile Demonstration Garden

The Chile Pepper Institute at NMSU conducts tours of their demonstration garden featuring hundreds of worldwide varieties of chiles. You can also visit their office and library on the second floor of Gerald Thomas Hall on campus. For more information, contact Danise Coon, 505-646-3028. Web site: www.chilepepperinstitute.org

New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum

Located on Dripping Springs Road (the eastern extension of University Boulevard), two miles east of I-25, this spectacular museum tells the story of the thousands of years of agriculture in New Mexico and has displays of livestock. For more information, call 505-522-4100. Web site: www.frhm.org

Hatch Chile Festival

Each year over the Labor Day weekend, the population of Hatch multiplies by a factor of ten during the annual festival featuring great food, agricultural displays and contests, vendor booths, and entertainment. For more information, call 505-267-5050.

Whole Enchilada Fiesta

Held in late September in downtown Las Cruces, this annual event features the making of the World’s Largest Enchilada, which is very spectacular. There are vendor booths, hot food, and great entertainment. Read more at www.twefie.com or call 800-FIESTAS.

Shops

Hatch Chile Express, 622 Franklin Street, Hatch. 505-267-3226. This is a great shop featuring every conceivable chile item, including fresh chile in season and dried and frozen year-round. Website: www.hatch-chile.com

Ristramnn (not a typo) Chile Company, 2531 Avenida de Mesilla in La Mesilla, features ristras, imported chiles, and fresh chiles in season. 505-526-8667.

Stahmann’s Country Store, 22505 Highway 28, south of Las Cruces in the middle of a huge pecan grove. 800-654-6887. Although pecans are featured in this large store, there are a lot of great chile products here. Website: www.stahmanns.com

Las Cruces Farmers & Craft Market, Downtown Mall, Saturdays and Wednesdays, 8 am to 12:30 p.m. Contact Olivia Martinez, 505-541-2556. Chiles of all kinds in season.

Restaurants

Chope’s Bar and Café, Highway 28 in La Mesa, 16 miles south of Las Cruces, 505-233-9976. This is like dining in someone’s house. In fact, it is an old house, and they serve great green chile enchiladas.

La Posta, just off the Plaza in Mesilla, 505-524-3524. Open seven days a week serving classic southern New Mexican cuisine. This is the most famous restaurant in southern New Mexico. A former stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail Route, the sprawling building is more than 180 years old. A must-stop for the chile tourist.

Peppers on the Plaza, 2355 Calle de Guadeloupe, Mesilla, 505-523-4999. Creative New Mexican cuisine. Serving lunch, dinner and Sunday brunch.

Pete’s Hacienda, 2605 S. Espina, Las Cruces, across from the University, 505-532-0790. New Mexican cuisine along with steaks and seafood. Serving lunch and dinner.

Recipes

Chile Pasado (Dried Green Chile)

This dark, blackish-green rather nasty looking dried green chile becomes plump, soft, tasty, and almost green when re-hydrated. It keeps forever or longer and was the method of preserving fresh green chile before refrigeration. You can dry these chiles in a variety of ways depending on whether you live in a dry climate like New Mexico or Arizona or not.

-

2 pounds, approximately 20 pods of New Mexico green chile

Before you dry the green chiles, you must first roast and peel them (see p. 37). To dry the chiles, use any of the following methods. Drying times will vary, but dry them until they are very dark and brittle.

-

Tie four pods together by wrapping string around the stems and place over a line outside in the sun. Do not let the chiles get wet by rain, and protect them from flies and other insects by wrapping them lightly in cheesecloth.

-

Lay the chiles on screening in a single layer, place in the sun, and protect them by covering with cheesecloth. With this method, you don’t have to worry about leaving the stems in tact.

-

Dry them in a dehydrator until they darken and become brittle.

-

Place them on a rack in the oven set at the lowest heat possible. Monitor them closely so they don’t burn.

To store the chile, place in a plastic bag and keep in a cool dark place or keep the bag in the freezer until used.

To reconstitute the pods, break off the stems, place them in a bowl and cover with very hot water. Allow them to steep for 15 minutes or until soft. Drain the chiles and discard the water.

Use reconstituted chile pasado in any recipe calling for green chile in any form except whole pods.

Yield: About 3 ounces

Heat Scale: Varies but usually med-ium

Rajas, or strips of green chile, are commonly cooked with other vegetables. But New Mexican chile has such a great flavor that the rajas can stand alone. Serve these tasty appetizers with toothpicks. Note: This recipe requires advance preparation.

-

5 green New Mexican chiles, roasted, peeled, seeds and stems removed, cut into strips

-

1/4 cup olive oil

-

1/4 cup red wine vinegar

-

1 clove garlic, chopped fine

Combine all ingredients in a bowl, cover, and marinate in the refrigerator overnight.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Mild to medium

Green chile sauce is a classic, all-purpose sauce that is basic to New Mexican cuisine. It’s at its best made with fresh green chile although canned chile can be substituted. Finely diced pork can be added, but cook the sauce for an additional half hour if you do add it. This is a lightly flavored sauce, with a pungency that ranges from medium to wild depending on the heat of the chiles. Traditionally this sauce is used over enchiladas, burritos, eggs for breakfast, or chiles rellenos, but its’s also is a tasty addition to nontraditional recipes as well. It will keep for about 5 days in the refrigerator and freezes well.

-

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

-

1/2 cup finely chopped onions

-

1 clove garlic, minced

-

1 tablespoon all-purpose flour

-

2 to 3 cups chicken broth

-

1 cup chopped green New Mexican chiles, roasted, peeled, stems and seeds removed

-

1 small tomato, peeled and chopped

-

1/4 teaspoon ground cumin

-

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Heat a heavy skillet over medium heat, add the oil and when hot, add the onion and garlic and saute until they are soft. Stir in the flour and blend well. Simmer for a couple of minutes to cook the flour, being careful it does not brown. Slowly add the broth and stir until smooth.

Add the remaining ingredients, bring to a boil, reduce the heat and simmer until the sauce has thickened, about 15 minutes. Taste and adjust the seasonings.

Yield: 2 to 3 cups

Heat Scale: Medium to Hot

Nothing beats snacking on chips dipped in chile con queso while drinking a Negra Modelo and watching football. Here is a slightly different take on the dip, one that avoids American or processed cheese.

-

1/4 cup butter

-

1 cup chopped green New Mexican chiles

-

2 serrano chiles, stems and seeds removed, minced

-

2 cloves garlic, minced

-

1 cup minced onion

-

1 cup diced fresh tomatoes (skins and seeds removed)

-

1/4 cup minced fresh cilantro

-

1 cup grated sharp cheddar cheese

-

1 cup shredded pepper jack cheese

-

2 tablespoons sour cream

-

Tortilla chips for dipping

Heat the butter in a saucepan and saute together over medium heat the green chile, serrano chile, garlic, onion, tomatoes, and cilantro for about three minutes, stirring occasionally. Add the cheeses, stir, cover, and cook for 1 minute. Remove from the heat and allow to sit for 2 minutes. Pour the mixture into a bowl and top with the sour cream.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Chiles rellenos literally means “stuffed chiles,” and in Mexico many different chiles are used, including poblanos, jalapeños, rocotos, and even fresh pasillas. Here in the Southwest, we prefer New Mexican green chiles. Whatever type of chile you use, the preparation and fillings are the same.

-

2 tablespoons butter

-

1 medium onion, chopped

-

2 cloves garlic, minced

-

1 1/2 cups cooked whole kernel corn

-

1 teaspoon dried oregano

-

1/3 cup sour cream

-

6 ounces cheddar cheese, cubed

-

6 green New Mexican chiles, roasted and peeled, stems left on

-

Flour for dredging

-

3 eggs, separated

-

1 tablespoon water

-

3 tablespoons flour

-

1/4 teaspoon salt

-

Vegetable oil for frying

-

Green Chile Sauce (see recipe)

In a skillet, heat the butter and saute the onion and garlic until soft. Add the corn and oregano and cook for an additional 5 minutes. Remove from the heat and stir in the sour cream and cheese.

Make a slit in the side of each chile and stuff with the corn mixture. Dredge the chiles in the flour and shake off any excess.

Beat the egg whites until they form stiff peaks. Beat the yolks with the water, the tablespoon of flour, and the salt. Fold the yolks into the whites and stir gently.

Dip the chiles in the egg batter and fry one at a time in 1 to 2 inches of oil until they are golden brown.

Serve covered with green chile sauce.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Of course, we have our own version of pesto! It’s a topping for pasta but also can be added to soups, stews, and rice. Although we have specified cilantro in this recipe, you can use the traditional basil or even Italian parsley. Pecans, another New Mexican crop, can be substituted for the piñon nuts.

-

1 cup chopped green New Mexican chile

-

1 cup chopped fresh cilantro

-

1/3 cup piñon nuts

-

1/2 cup grated Parmesan or Pecorino Romano cheese

-

1/2 cup virgin olive oil

Place the chile, cilantro, nuts, and cheese in a food processor and, while processing, slowly drizzle in the oil to form a pesto.

Yield: 1 1/2 cups

Heat Scale: Medium

Tomatillo-Chicken Enchiladas with Two Kinds of Green Chile

New Mexican cooks are forever improvising on traditional recipes. This interesting variation on green chile and chicken enchiladas has been tested so many times in our kitchens that we now consider it a New Southwest classic. The enchiladas go well with traditional dishes of rice, refried beans, and a crisp garden salad.

-

4 chicken breasts

-

8 ounces cream cheese

-

1 cup onion, chopped fine

-

1 cup heavy cream or half and half

-

3 green serrano chiles, stems and seeds removed, chopped fine

-

5 green New Mexican chiles, roasted, peeled, seeds and stems removed, chopped

-

1 cup finely chopped tomatillos

-

1/4 cup chopped fresh cilantro

-

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

-

1 egg

-

Vegetable oil for frying tortillas

-

12 corn tortillas

In a pot, cover the chicken with water, bring to a boil, reduce heat and simmer 30 minutes. Remove the chicken and reserve the stock. When the chicken has cooled, remove the skin and meat. Shred the meat using two forks.

Combine the cream cheese, onions, and 1/4 cup of the cream. Add the chicken and mix well.

Place the serranos, green chile, tomatillos, cilantro, pepper, egg, remainder of the cream, and 1/3 cup of the chicken stock in a blender and puree to make a smooth sauce.

Heat a couple of teaspoons of oil in a small skillet until hot. Using tongs, fry each tortilla for a few seconds on each side until soft, taking care that they do not become crisp. Remove and drain.

To assemble the enchiladas, dip a tortilla into the green sauce and place it in a shallow 9 x 13 inch casserole dish. Spread about 1/4 cup of the chicken mixture in the center of the tortilla, roll it up and place it at the end of the dish with the end side down. Repeat the process until the enchiladas form a single layer in the dish. Pour the remaining sauce over the enchiladas.

Bake the enchiladas, uncovered, in a 350 degree F oven for 20 minutes and serve immediately.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Here is one of our favorite ways to cook rice. The style is from the Middle East, but the chile transforms the dish into a favorite New Mexican accompaniment. Believe it or not, some people serve salsa over this rice!

-

2 ounces butter

-

2 cups long-grain white rice

-

1 onion, chopped fine

-

2 cloves garlic, minced

-

2 red New Mexican chile pods, seeds and stems removed, soaked in hot water to hydrate them

-

4 1/2 cups chicken stock

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees F.

In a sauce pan, melt the butter over medium heat and saute the rice until golden brown, stirring often. Add the onion and saute until soft, about 3 minutes, taking care that the rice does not burn. In a blender, puree the garlic, chile, and 1/2 cup of stock. Add this to the rice and stir. Add the remaining stock to the rice, bring to a boil, and transfer to a deep glass baking dish. Cover and bake for 45 minutes, removing the lid during the final 10 minutes. Fluff with a fork and serve.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Mild