by Dave DeWitt

|

Part 5: We Know Beans About It: The Chili Pantry

|

Recipes: Beans for Chili! Sam Pendergrast’s Original Zen Chili Lady Bird Johnson’s Pedernales River Chili Chef Heywood’s Chili

|

We’ve discussed the chiles and meat in chili, but there are quite a few more ingredients to analyze for the classic bowl o’ red.

Garlic, Onions, and Tomatoes

Chili purists often preach that garlic is necessary to good chili, but that onions and tomatoes are worthless. “Garlic sweetens and deepens the pungent flavor of chili without adding liquid (as do onions),” observed John Thorne. “It is a necessary part of the true ‘grease and gladness’ bowl of Texas red.” As usual, a chorus of protests will rise from other cooks, like Floyd Cogan, who noted that “although you can make good chili from garlic alone, adding a good sized onion does wonders for it.”

Besides the argument over garlic versus onions, some cooks even debate whether or not these ingredients should be sauteed first before adding them to the chili pot. The consensus seems to be that it makes no difference at all. All cooks seem to agree that fresh garlic and onions are mandatory and that garlic or onion powder, salt, flakes, or liquid are forbidden. “The flavors and aromas of onions and garlic are generally attributable to allyl sulfides,” remarked our chili chemist, Dr. Crum.

|

|

Gotta have some Garlic!

|

“With the possible exception of beans,” wrote Bill Bridges, “no ingredient provokes more controversy among chili cooks than the tomato.” Indeed, E. DeGolyer noted that: “Many cooks add ripe or canned tomatoes. We regard this as effeminate.” John Thorne believes that: “Tomatoes and onions worked their way into chili from a familiar Southwestern dish called chile colorado (“red chile”) which at one time referred both to a sauce of fresh red chile peppers and a stew made from them, usually of chicken, which often included tomatoes and onions. Since then, chili-makers who interpret chili as a bowl of grease and gladness eschew them while those more in sympathy with the dish’s indigenous heritage embrace them.” Some cooks, particularly Texans, take exception to the very idea of tomatoes in chili, although Wick Fowler used them both privately and in his commercial concoctions.

Cooks should remember that tomatoes add acidity to chili, but not with the sharpness of vinegar or lemon juice. Tomatoes used fresh should be peeled and seeded. Peel the tomatoes by plunging them in rapidly boiling water for a minute or so. When you see the skin split, remove the tomato and the skin will easily slip off. The seeds can be removed by cutting the tomatoes into quarters and gently squeezing out the liquid and seeds. If you are a lazy chili maker, you might use canned tomatoes, tomato juice, or even tomato sauce–just don’t tell anyone.

Beans or No Beans

Beans are the biggest controversy in chili cookery–so big, in fact, that Joe Cooper named his book With or Without Beans. Cooper spent nine pages discussing the debate and concluded that “An assay of all material accumulated indicates a preference for with beans.” That was in 1952. In 1981, when Bill Bridges wrote on chili, he cited Ray Shockley of Wolf Brand Chili as the source for the following statement: “In Texas, the preference for straight chili runs about three to one, while almost everywhere else in the country, chili with beans is preferred by the same majority.” Nowadays, as we all know, beans are eschewed rather than chewed in competition chilis. In the rules of the Iowa Chili Appreciation Society, a member of CASI, “Anybody who knows beans about chili knows there ain’t no beans in chili. The addition of beans, macaroni or other fillers will cause disqualification.”

|

|

Pinto Beans Are the Favorite Beans

|

There are some pretty good reasons for cooking “straight” chili, or that without the beans. The most basic reason is that once beans are in the chili, they cannot be removed. At a dinner party, some guests will understandably be upset to find beans in their chili. However, beans can always be added to chili when it’s served at the table, which is considered to be proper chili etiquette in the Southwest.

John Thorne detailed another good reason for keeping the beans out of the bowl of red: “Chili made with beans can’t be reheated, since the beans get sour and turn to mush. But real (no bean) chili requires reheating to reach its final patina of perfection. If you are served beans in your chili, however, you should show forbearance–simply pick them out and quietly slip them under the table.”

|

|

More beans:

|

Let’s assume for the moment that we take the side of the chili with beans contingent. Now, what kind of beans to use? Red kidney beans and pinto beans seem to run neck and neck in the competition, with some competition from Louisiana red beans and, according to Joe Cooper, pink bayou beans. He wrote, though, “Chili is no place for limas, navys, and black-eyed peas.” Some modern chili recipes call for black beans, which we love. They are not authentic, but are probably the best tasting beans.

George C. Booth, author of The Food and Drink of Mexico, observed, with a sexist slant: “Making a good chile con carne is like making a good marriage; you give the same narrow eyed scrutiny to finding the right type of bean that you would to choosing a wife. Look for sturdy character, consistent quality, and recognized breeding.” He suggested the Mexican red bean.

Whatever beans are chosen, they must be cooked in some manner. Everyone agrees (a miracle in itself) that raw beans cannot be added to chili and even beans that have been soaked overnight in water take longer to cook than the chili itself–up to six hours. So beans are definitely cooked first, and don’t make two crucial mistakes. First, never cook the beans in salted water, because they will be tough–only add salt after the beans are cooked. And second, never add half-cooked beans to the other chili fixings and expect that the beans to be done when the chili is. The half-cooked beans will never soften.

“The bean cell wall hemicelluloses,” explained Dr. Crum, “are more soluble in alkaline conditions, and the experienced chili cook knows that partially cooked beans, when added to the acidic conditions in partially cooked chili, will simply not get any softer as you continue the cooking process.” The solution, of course, is to pre-cook the beans to their desired softness. We have included a basic bean recipe in this chapter which is designed to be combined with chili during its final serving–if the cook is daring enough to face the cook-off experts in the crowd.

|

|

The Winter 1989 Chili Cover

|

Of course, one inherent problem with beans is that they are, indeed, the “musical fruit.” Richard L. Potts, M.D., addressed this problem in an article for Chile Pepper magazine, when I was the editor. “The combination of beans and beer tastes good to me–way too good,” he wrote. “The problem is, a couple of hours later, it’s rumble time, usually followed by eructation (belching), distention, and, eventually, dreaded flatulence. It’s only a matter of time before the enzymes in my small intestine reject my beans and beer. They are unable to digest, chemically, all that I have consumed. A little further along, two non-absorbable carbohydrates face off against the intestinal bacteria down there in my large intestine. The resulting chemical clash produces various gasses in quantities large enough to inflate the Goodyear Blimp. Ever so slowly, the gas accumlates. It pushes outward. It meets resistance. The skin covering my belly stretches. My colon is swollen. The expansion continues as the gas seeks the path of least resistance, and with various embarrassing sounds, vents my body.” His description is enough to ban beans forever from chili!

One final word on beans from Floyd Cogan: “Please! Never used canned pork and beans or Boston baked beans in your chili–use them only when you are desperate or faced with an extreme emergency. Even then don’t let anyone see you.”

Cumin and Oregano

Cumin is the principal spice in chili, and its distinctive taste reminds people of both Mexican and Indian foods, which often contain quite a bit of it. Since cumin is also an ingredient in chili powder, some recipes give a double dose of this spice. “If you note a vaguely sweaty aftertaste to your bowl of red,” John Thorne wrote, “someone had an over-eager hand with the cumin. It is undeniably popular with Texas chili-makers, who sometimes use more of it than they do chile itself.” Indeed they do, for in Sam Pendergrast’s Zen Chili recipe below, he calls for an astounding one-half cup of cumin seed!

|

|

Cumin, whole and ground

|

The best cumin is fresh cumin seed, which should be kept in an airtight container in the freezer. For recipes that do not call for the whole seeds, the cumin seed must be ground–but first, toast them. Place the cumin seed in a dry, clean skillet and apply heat. Stir the seeds constantly until they release their aroma and turn a light brown color. Grind them with a mortar and pestle or use a spice mill.

|

|

Too Much Cumin Will Do This To You (See the Zen Chili Recipe)

|

Not all oregano is oregano. The European, or Greek oregano is actually wild marjoram (Origanum vulgare) that was also called oregano. The Caribbean oregano of Cuba, Trinidad, and Yucatán is really a coleus known as borage, which is also called Spanish thyme. The Mexican oregano (Lippia graveolens), which is stronger, is the true oregano for chili. Mexican oregano is usually sold in its dry form, but cooks can easily raise their own in herb gardens. If you can’t find Mexican oregano, use marjoram.

Other Herbs, Spices, and Ingredients

Floyd Cogan lists twenty-eight additional herbs and spices used in chili recipes (nearly everything on the spice shelf at the supermarket), and Bill Bridges lists twenty-two such ingredients. The most popular seem to be black pepper, basil, coriander seed, cilantro (fresh coriander leaf), bay leaf, thyme, sage, anise seed, cloves, nutmeg, and caraway. Cinnamon and allspice are common ingredients in Cincinnati-style chili. Some far-out herbal additives in other chilis range from turmeric to cardamom to fennel to mustard seed to mace to even woodruff and Texas farkleberries. The amounts and combinations of such ingredients are part of the mystique of chili and are always determined by trial and error by each individual cook. Chocolate has long been used in its various forms; Joe Cooper used cocoa in his 1952 recipes, and unsweetened chocolate appears commonly in Cincinatti-style chilis.

Salt and sugar are ubiquitous in chilis–always to the cook’s taste. However, as usual, it’s not as simple as that. Arizona chili expert Andy Housholder devotes several pages to the subject in his technical treatise on championship chili. “A slight sweet and a tad over-salted chili is more important to pick up judges’ points than the correct blend of other chili flavors,” he wrote. Housholder advised using only dark brown sugar and then only during the last 45 minues of cooking. If it is to be added during the last ten minutes, it should be liquid brown sugar. He also recommended using only non-iodized salt.

Weird Stuff: Ingredients That Do Not Appear in This Project’s Chili Pantry

Here is a list of ingredients appearing in some nefarious chilis (but not ours): Almonds, aquavit, avocados, barley, bitters, carrots, celery, Coca Cola, coffee grounds, corned beef, currant jelly, curry powder, goose grease, horseradish, molasses, mushrooms, olives, Parmesan cheese, peanuts, peanut butter, pea pods, raisins, sake, spinach, water chestnuts, vinegar, and Worcestershire sauce.

Recipes

This recipe is considered to be the basic one for beans that will be added to chili when it’s served–assuming, of course, that you are a “with beans” aficionado. There is a great debate about whether or not to soak the beans overnight. The only simple answer is that if the beans are soaked overnight, they will take about half as long to cook the next day.

-

1 pound dried pinto or kidney beans, cleaned and soaked overnight in 3 quarts cold water

-

3 more quarts cold water

-

Salt to taste

Remove any beans that float, then drain the beans and replace the water with 3 quarts of fresh cold water.

Bring to a boil, reduce the heat and simmer, uncovered for 2 to 3 hours or until the beans are tender and are easily pierced with a fork. If additional water must be added, use only hot water.

Drain the beans and add salt to taste.

Yield: 6 cups

Sam Pendergrast’s Original Zen Chili

Here is Sam’s recipe for good ol’ café chili. Note the extreme amount of cumin. Interestingly enough, in the version of this recipe which appeared in Texas Home Cooking, the amount of cumin mysteriously was doubled. Could Sam be addicted to cumin? Sam is also the author of Avenida Juarez, a novel which has to be read to be believed.

|

|

The Cover of Sam’s Book on Zen Chili

|

The recipe is in Sam’s words, unedited.

-

1 pound fatty bacon

-

2 pounds coarse beef, extra large grind

-

½ cup whole cominos (cumin seed–yes, one-half cup!)

-

½ cup pure ground New Mexican red chile

-

Water

-

1 teaspoon cayenne

-

Salt, pepper, and garlic powder to taste

Render grease from the bacon; eat a bacon sandwich while the chili cooks. (Good chili takes time.)

Saute the ground beef in bacon grease over medium heat. Add the cominos and then begin adding the red chile until what you are cooking smells like chili. (This is the critical point. If you add all the spices at once, there is no leeway for personal tastes.) Let the mixture cook a bit between additions and don’t feel compelled to use all of the red chile.

Add water in small batches to avoid sticking, and more later for a soupier chili. Slowly add the cayenne powder until smoke curls your eyelashes. Palefaces may find that the red chile alone has enough heat.

Simmer the mixture until the cook can’t resist ladling a bowlful for sampling. Skim the excess fat for dietetic chili, or mix the grease with a small amount of cornmeal for a thicker chili.

Finish with salt, pepper, and garlic powder to individual taste, paprika to darken. Continue simmering until served; continue re-heating until gone. (As with wine, time enobles good chili and exposes bad.)

The result should be something like old time Texas café chili: a rich, red, heavily cominesque concoction with enough liquid to welcome crackers, some chewy chunks of meat thoroughly permeated by the distinctive spices, and an aroma calculated to lure strangers to the kitchen door.

Yield: 4 servings

Heat Scale: Hot

Variation: For cook-off contest chili, drink bad tequila two days before starting the chili; burn mixture frequently; sprinkle occasionally with sand and blood; serve cold to a dozen other drunks and call them “judges”; and keep telling yourself you’re having a great time.

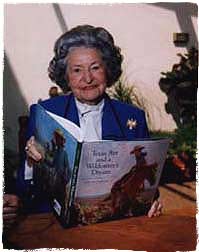

Lady Bird Johnson’s Pedernales River Chili

This recipe originally contained beef suet, but that ingredient was omitted after LBJ’s severe heart attack when he was Senate Majority Leader. Remember to skim the fat off the chili. She wrote: “So many requests came in for the recipe that it was easier to give the recipe a name, have it printed on a card and make it available. It has been almost as popular as the government pamphlet on the care and feeding of children.”

|

|

Lady Bird Johnson

|

-

4 pounds coarsely ground beef

-

1 large onion, chopped

-

2 cloves garlic, chopped

-

1 teaspoon oregano

-

1 teaspoon ground cumin

-

6 teaspoons New Mexican red chile powder (or more for heat)

-

2 16-ounce cans tomatoes

-

2 cups hot water

-

Salt to taste

Combine the beef, onion, and garlic in a skillet and sear until the meat is lightly browned.

Transfer this mixture to a large pot, add the remaining ingredients, and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer for an hour.

When done, transfer the chili to a bowl and place it in the refrigerator. When the fat has congealed on top, remove it with a spoon.

Reheat the chili and serve it as LBJ liked it–without beans and accompanied with a glass of milk and saltine crackers.

Yield: 12 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

This chili is from the C.I.A.–the Culinary Institute of America, where Chef Jim Heywood taught for many years. He competed in fifteen chili cook-offs in 1992. “I’ve won a few along the way,” he notes, “including the Connecticut State Championship in 1988 and the New Hampshire State Championship in 1991. Jim is also one of the star guest chefs at the National Fiery-Foods & Barbecue Shows in Albuquerque.

|

|

Chef Jim Heywood, formerly of the C.I.A.

|

-

5 pounds lean beef (chuck or round), diced in ½-inch pieces

-

1/2 cup vegetable oil

-

1.5 pounds onions, diced

-

6 cloves garlic, minced

-

2 cups dark beer

-

2 cups beef broth

-

1 6-ounce can tomato paste

-

1.5 cups diced New Mexican green chiles that have been roasted and peeled

-

2 to 3 jalapeños, stems and seeds removed, minced very fine

-

3/4 cup chili powder

-

3 tablespoons freshly ground cumin seed

-

1.5 tablespoons dried oregano

-

Salt and pepper to taste

In a large pot, brown the beef in the oil. Remove and reserve the beef, leaving the oil in the pan.

Saute the onions and the garlic in the remaining oil until soft. Add the beer, reserved beef, and tomato paste and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer for 1 hour, stirring frequently.

Add the remaining ingredients and simmer for another hour, stirring frequently.

Yield: 12 to 14 servings for hungry chili addicts

Heat Scale: Hot