By Harald Zoschke

SuperSite Recommendations

Chile Pepper Bedding Plants… over 500 varieties from Cross Country Nurseries, shipping April to early June. Fresh pods ship September and early October. Go here

Chile Pepper Seeds… from all over the world from the Chile Pepper Institute. Go here

|

Saga Jolokia – Searching for the new “World’s Hottest Chile” By Harald Zoschke, with input from Dr. Paul Bosland and Dave DeWitt

Posted November 17, 2006 – Updated throughout 2007

It’s been more than five years that an Indian “Mystery Chile” was making headlines, and claims for such a “new” variety were published in print, and all over the Internet. With almost one million Scoville Units, it was supposed to be several times hotter than the Red Savina™, the current holder of that title in the Guinness World Records. Time and again the hot pod popped up in the news, yet no one in the Western world had seen it. That has changed recently, as new claims for such a potent pepper came from the UK, and also from the renowned Chile Pepper Institute of the New Mexico State University. First Sightings

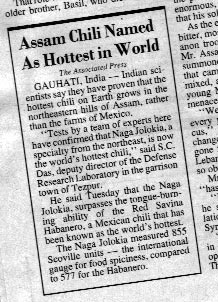

In September 2000, we got hold of a newspaper clipping from the International Herald Tribune. Headlined “Assam Chile named Hottest in the World”, AP had a brief story about a chile pepper variety grown in the northeastern hills of Assam, India. With 855,000 Scoville Heat Units (SHU), it would outperform the Red Savina’s much-quoted (and never duplicated) heat level of 577,000 SHU. The source given for that newsbyte was S.C. Dass, deputy director of the Defense Research Laboratory in the Assamese town of Tezpur.

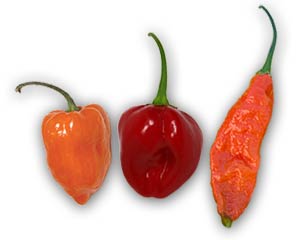

At that time, the ‘Naga Jolokia’, also named the ‘Tezpur’ in some reports, was said to be a member of Capsicum frutescens, the same species as the ‘Tabasco’ chile, while the blistering hot ‘Red Savina’ is a Capsicum chinense. And this statement from the Indian researchers alerted Frank Garcia of GNS Spices, the Californian developer and grower of the ‘Red Savina’, listed so far as the world’s hottest pepper in the Guinness World Records. Regular red and orange habaneros are typically in the 150,000 to 300,000 ballpark.

“It would be highly unusual for a frutescens to be that hot,” Garcia said in an interview with fiery-foods.com. With some Savina record challengers, Garcia also questioned the reliability of the test results: “In some cases labs have discovered that the challengers’ samples have been adulterated with oleoresin,” the extremely hot capsaicin extract, thus disqualifying them. “But anything’s possible,” he said of the ‘Naga Jolokia’, “so, bring it on and let’s get some American laboratories to test samples of both the Indian chile and the ‘Red Savina’ and see which is the hottest.” The cited heat level of 855,000 SHU obviously came from this August 2000 report that was published in the journal ‘Current Science’, giving somewhat more detail. The PDF version is still available here.

Response by the Chile Pepper Institute and by Dave DeWitt

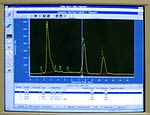

As Dave noted back then, the report was interesting for the lack of detail of the methodology used to calculate Scoville Units through HPLC (High Performance Liquid Chromatography). He asked Dr. Paul Bosland, the noted chile breeder at New Mexico State University to read the report in “Current Science” and to give us an opinion. Dr. Bosland pointed out that while the HPLC should be calibrated first by using a known concentration of capsaicin solution, there was no mention of such a procedure. This alone could account for measuring 100,000 SHU too much. He also questioned the preparation of the chiles — did they weigh the chile sample before extracting? Were the seeds, pericarp, and placenta ground together, or did they just pick the hot parts?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In light of Dr. Bosland’s skepticism, Dave repeated his challenge to the Indian scientists, Ritesh Mathur, R.S. Dangi. S.C. Dass, and R.C. Malhotra of the Defence Research Laboratory in Gwalior, India, to send him samples of the ‘Tezpur’ pods for testing by two U.S. labs — the one at New Mexico State University, and one at Analytical Food Laboratories. Frank Garcia agreed to provide his samples for a “hottest chile test-off.” Dave also emailed this challenge to the Indian scientists — in vain, though.

It should be mentioned that to date, there seems to be no evidence that anyone ever came close to duplicating the 577,000 SHU result published by Garcia for his Red Savina. In fact, typical heat results for Red Savina are more in the 250,000 SHU range – see also Heat Levels Reported as well as The The Australian Chile Test. In fact, Red Savina’s heat is often topped by Chocolate Habanero, and we haven’t even tested the blistering hot Central African Fatalii yet… Over the past years, several chile varieties surfaced and claimed to be the famous ‘Naga Jolokia’, or ‘Tezpur’ pepper, including Indian PC-1 . This slim red pepper, a member of the Capsicum frutescens species, tasted more like Cayenne, and similar to it, the pepper scored only five-digit Scoville results. No wonder we suspected rather soon that this kind of pepper was no challenge to Frank Garcia’s Red Savina, belonging to Capsicum chinense, just like Habanero and other six-digit heat Scoville power-packs. A first clue that the infamous ‘Naga Jolokia’ had to be a chinense member, too, came in 2003. For a special issue on international chile peppers that Dave contributed to, the Japanese magazine, Paper Sky, sent a reporter all the way to Tezpur, to check out the claim about this pepper. The reporter, Graham Simmons, soon discovered that the chile was named after the ferocious Naga warriors, who once inhabited Nagaland in Assam, one of India’s most fertile regions. Accompanying the article was a photo of a rather dried out plant that still had some orange-red pods on it. The pods were clearly Capsicum chinense, the species containing the habaneros. So at least the species mystery was solved — but what about that HPLC test? Unfortunately, Simmons did not speak directly to the Indian scientists, and even if he did, it would be too much to hope that he quizzed them about their testing methodology.

More proof that Naga Jolokia was most likely a chinense chile came from a 2004 fiery-foods.com reader. He reported that they had a lot of curry houses in Japan, and they would make some extremely spicy dishes, many with Indian Tezpur. Some of these restaurants even have jars of whole Indian Tezpurs sitting on shelves, he went on, looking much like a Caribbean Habanero, just a little bigger.

Finally – The Mystery Pepper becomes RealityAnother two years went by until the “Saga Jolokia” made significant progress. Also the Chile Pepper Institute grew and analyzed all sorts of capsicum varieties that were supposed to be “the world’s hottest.” Most of the time, the results were rather disappointing. One variety showed potential, though — in 2001, the Institute received seed of a chile named ‘Bhut Jolokia’ from a member who had collected it while visiting India. Because of poor fruit and seed set, it took Dr. Bosland several years to have sufficient seed on hand for an extensive field trial. ‘Bhut Jolokia’ was grown under insect-proof net cages to produce the bulk seed, and by 2004, enough seed was available for the test. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extensive Field Trial and Tests in New Mexico

Now Dr. Bosland and his colleagues were ready for a large-scale experiment. An extensive study was undertaken, with three goals:

The comparison experiment was conducted in 2005 at a plant science research facility close to Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Using a climate-controlled greenhouse and heat pads, seeds of all three varieties were started and thinned after germination. When seedlings had developed eight to ten true leaves, they were transplanted to the field plots or to 4 liter (1 gal) plastic pots and grown in the greenhouse for DNA extraction. In the field, they were were planted in a sophisticated, randomized pattern, forming blocks of 36 plants each. A single line of plants was spaced 25 cm (about 1 foot) apart within the row and 1m (3 ft.) between rows. The plants were grown using standard cultural practices for growing chile peppers in southern New Mexico. As customary in the “Chile Pepper State”, the plots were furrow irrigated throughout the season to maintain optimal plant growth. Fortunately, 2005 weather conditions proved to be favorable for this sort of field test. Once the fruit had matured, harvest also followed a highly scientific scheme. To get a good fruit average of each variety, the scientists harvested 25 random mature fruits from at least 10 plants. To prepare for HPLC Scoville testing, the whole sample pods were dried and ground. ‘Bhut Jolokia’ was also used for DNA testing. As most of us know from watching CSI on TV, DNA is the genetic fingerprint of all life forms. Not only bad guys can be identified accurately and quickly that way, but the various species of capsicum as well. So-called RAPD markers show a typical pattern of stripes that can be matched against other samples (RAPD – not to confuse with LAPD – stands for “random amplification of polymorphic DNA” – more on Wikipedia here). To be able to create such fingerprints of various Capsicum species as a reference, the scientists at the Chile Pepper Institute obtained various samples of C. annuum, C. baccatum, C. chinense, and C. frutescens — these plant materials were acquired from germ plasm collections like the National Plant Germplasm System. For DNA isolation, samples of leaf tissue were taken. So instead of CSI, we had CPI investigating here. By comparing Bhut Jolokia’s RAPD markers with the reference markers, is was possible to determine which species’ genes are part of this particular pepper variety. That, of course is much more accurate than just by observing how many pods per node are growing, or by comparing flower types, which is of course still done in addition as well. Both the HPLC test and the DNA analysis brought valuable insight into this exciting chile pepper from India.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interesting Results

Heat Levels, and who’s the Hottest in the World Let’s begin with the capsaicin content using the HPLC test. Besides the makeup of a pepper cultivar’s genes, environmental factors are known to increase or decrease the actual heat level as well, but being able to compare the samples with standard control cultivars from field trials increases the confidence of the heat level measurements. The HPLC data were converted from ppm (parts per million) to SHU by multiplying it by 16. For example, if a total capsaicinoid content of 36000 mg/kg is determined, multiplying this value by 16 would mean 576,000SHU (for SHU, capsaicinoids like capsacin, dehydrocapsaicin etc. are summed up.) Side note — Some years back, pure capsaicin was defined as 15 million SHU. Accordingly, the factor 15 then. With current standards’ assumption of capsaicin being 16 million SHU, the factor should be 16, not 15. I verified this with both CPI and a certified food lab. Some testers still seem to work with a factor of 15, which gives results that are about 6% lower.

The HPLC analysis revealed that Orange Habanero had a mean (average) heat level of 357,729 SHU. That’s quite a bit, but according to Dr. Bosland, this is in the range normally seen for this cultivar in Las Cruces, NM. (I once tasted Jalapeno peppers right from a field close to Las Cruces, and even those “ordinary” peppers were surprisingly hot.) Now for Bhut Jolokia — the analysis revealed that it possessed an extremely high heat level indeed, a whopping 1,001,304 SHU. That’s a heat level you normally see only with ultra-hot sauces using pepper extract (capsicum oleoresin). A different kind of surpise was the test result for Red Savina – it scored a rather low heat level of just 248,556 SHU. This means the SHU value for ‘Bhut Jolokia’ was four times higher than ‘Red Savina’ — so much for “the world’s current hottest chile pepper” In 2004, Assam-based pepper grower Frontal Agritech also had their Bih Jolokia chiles HPLC-tested and reported 1,041,427 SHU, which means two independent results for Jolokia are in the same ballpark. The Northeastern-Indian region allows for two harvests per year, though and there seems to be a certain seasonal heat fluctuation between the two. Two UK growers reported quite similar results for Naga Jolokia type peppers, using greenhouses. In general, these heat level results can only serve as a reference. While the hot southern New Mexico desert climate pushed Bih Jolokia to almost one million SHU, pods from the same seedstock may deliver considerably less capsaicin on a raised bed after a rainy summer in Cleveland. Then again, optimized nutrition and environmental conditions in a greenhouse could possibly yield even higher SHU results. In addition to that, unverified third party HPLC results should always be taken with a grain of salt. Remotely related Anecdote…. While running Peppers on the Pier, a “hot shop” in St. Petersburg, Florida, we employed a great guy as a salesperson, his name was Tom. Frequently shoppers came in and asked “What’s the hottest in this store?” — and Tom would reply: “That would be me.” DNA Results Now let’s take a look at the DNA test of ‘Bhut Jolokia’, researching its species. As mentioned, early Naga Jolokia or Tezpur reports insisted that this pepper would belong to the C. frutescens species. Next came evidence that this was a C. chinese type of chile. So what is it really? Well, it’s a chinense, but the frutescens proponnents were not completely wrong. Among the 19 samples of C. annuum, C. frutescens, C. chinense, and ‘Bhut Jolokia’, the scientists obtained 136 reproducible and reliable polymorphic RAPD markers to work with. To sum up the rather complex test results, the researchers found eight RAPD markers specific to C. chinense, as well as three markers specific to C. frutescens. No annuum-specific patterns were detected in this Indian chile, but one that was specific to ‘Bhut Jolokia’. The genetic similarities among and within the species were calculated by applying some sophisticated algorithms that would be beyond the scope of this article. At the bottom line, the experts obtained a so-called “similarity index value”. A totally pure species would mean a value of 1.00, which is rather rare, as most cultivars (= cultivated varieties) contain genes from more than one species through breeding. The C. annuum samples included in this analysis for reference delivered a similarity index value of 0.86. Similarly, the C. chinense as well as C. frutescens reference samples showed similarity index values of 0.82 and 0.85, respectively. The C. frutescens and C. chinense clusters merged at the similarity index value of 0.45. The the average genetic similarity between C. chinense and ‘Bhut Jolokia’ was 0.79, which means this chile clearly belongs to the C.chinense species, but has some C. frutescens genes as well. According to Dr. Bosland, such a genetic species mix is not uncommon, and it is called “interspecific hybridization”. As an example, he mentioned the Greenleaf Tabasco cultivar — it was developed by interspecific hybridization between C. frutescens and C. chinense, followed by repeated backcrossing to C. frutescens. DNA analysis revealed that ‘Greenleaf Tabasco’ indeed contains some C. chinense genes. Considering that various C. frutescens peppers are cultivated in northeastern India as well (Indian PC-1 for example), the presence of some frutescens genes in this chinense cultivar should be no surprise. In Assam, plants of C. chinense and C. frutescens could have been grown near each other, allowing for hybridization between them, Paul Bosland remarked. Quite possibly, local farmers knowingly selected for a higher heat chile pepper, eventually leading to the ultra-hot ‘Bhut Jolokia’. 2.3 Million Scoville Heat Units for Bhut Jolokia? Let’s return to the heat level issue for a moment. In his conclusion, Dr. Bosland offered an interesting thought – pure speculation, of course: As we know, the environment can affect the heat level of a chile pepper. Under identical environmental conditions, ‘Red Savina’ recorded a mean heat level of 248,556 SHU, which is 232% below the highest heat level (577,000 SHU) published for this cultivar in the Guinness World Records. Now, if ‘Bhut Jolokia’ was grown under the very same conditions that produced the 577,000 SHU for ‘Red Savina’, a heat level of 2,323,025 SHU could be expected for ‘Bhut Jolokia’

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bhut Jolokia, Bih Jolokia, Naga Jolokia — what the …?

Bhut Jolokia, Bih Jolokia, Naga Jolokia, Naga Morich, Raja Mirchi … what’s the deal with all those different names you can read in print and on the Internet these days for supposedly the very same chile variety? We asked someone who should know best: Leena Saikia of Frontal Agritech, a pepper grower and processing company in Assam that also grows and cultivates Bih Jolokia. Here’s what Leena told me: “All these chillies are from North East India. They belong to Capsicum chinense. In fact, Naga jolokia, Nagahari, Bhut jolokia, Bih jolokia or Borbih jolokia are the same chilli but named differently at different places. For example, the Assamese community call it as Bih jolokia (poison chilli — jolokia means chilli in Assamese), Bhut jolokia (probably due to its ghostly bite or introduction by the Bhutias from Bhutan poison chilli) or Naga jolokia (due to extreme hotness representing the aggressive temperament of the warriors of neighbouring Naga community). In Nagaland and Manipur states, it is known as Raja Mircha or Raja chilli (King of Chillies). In major Indian languages, chilli is known as Mirch or mircha (Bengali and Hindi).” Morich” may be a distorted version of ‘mirch‘.

Bih Jolokia on a Frontal Agritech field in Assam (1) So how about this chile variety outside Northeastern India? Leena said: “We fully agree that these are of the same species and type which might have migrated to other nearby states and countries including Bangladesh and Srilanka where this chilli continued to be known as Naga Mircha (“Naga Moresh”). The original seeds of Dorset Naga were sourced from Bangladeshi community of Britain who might have taken the fruits of this chilli from Bangladesh for culinary purposes.” In their home country, Bhut Jolokia and Bih Jolokia are also spelled Bhwt Jolokiya and Bih Jolkiya respectively. In a blog we overheard this statement, obviously by a local as well: “It depends on where you grow it. If it is in Guwahati, it is Bhot Jalakia. In Jorhat it would be Bhut Jalakia. The end result is the same, you burn at both ends.” Confusing. There seem to slight differences between various flavors of this pepper, though. While the Assamese growers (Bih Jolokia) as well as the Chile Pepper Institute (Bhut Jolokia) report two flowers per node for their respective plants, we found clusters of up to five on the Naga Morich test plants we grew in our Pepperworld greenhouse from original “Chileman” seeds.

Also, depending on the source, certain calyx differences are evident, and also in fruit shape. Growing the various peppers next season will hopefully bring more insight, so some updates in the future are possible. With the potential to have the latest “Hottest Chile on Earth” in their hands that will kick Red Savina off its throne, it is no wonder that various parties are trying to market this pepper as “theirs.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hotter than the Hottest?

Indeed, some of the latest wave of “World’s Hottest Pepper” PR hype came from two chile gardeners in Great Britain. This is no wonder, as the UK has a huge Indian and Bangladeshi community that, among other spicy specialties, enriched the otherwise rather bland British cuisine with curry dishes. In fact, I am rather surprised that there was no sooner news about those ultra-hot Indian peppers in the UK. Mark McMullan a.k.a. “The Chile Man” advertises “Naga Morich”, offering peppers and seeds (Mark also runs a remarkable Chile Database). Joy and Michael Michaud (“Peppers by Post”) are promoting their version as “Dorset Naga”, also selling pods and seeds as a mail order business. And in Naga Jolokia’s country of origin, there’s Frontal Agritech, offering the dried fiery pods, grown on their own fields. Last but not least, there’s the Chile Pepper Institute, which offers seeds of the Bhut Jolokia chile. Mutual incentive is most likely the desire to be listed in the Guinness World Records, associated with the new “World’s Hottest Pepper.” There was even rumor that one party intended to file “their” Naga Jolokia version under the PVP. That’s short for Plant Variety Protection Act – sort of a patent and the method Garcia chose to make it so hard for the rest of the world to legally obtain pure Red Savina seeds. As Dave pointed out, this should be impossible with any Jolokia incarnation, as all the various parties did was selecting, not real breeding. Still we wouldn’t be surprised at all to see a “Naples Naga” or a “Moscow Morich” (“world’s hottest”, of course) popping up in the future, even if only on Ebay

Despite slight differences, all those various flavors of Naga Jolokia seem to have basically the same genetics and origin, and if heat level claims differ, it might be due to environmental influences, growing seasons, or non-standard HPLC tests. Expect any of those peppers to be in the same range – very, very hot. The chile community will greatly benefit from the widened availability through these various sources. It is advised though to buy from reliable sources — regarding chile seeds, we’ve heard more than once about disappointing Ebay deals. As chiles love to cross-breed, producing pure seeds takes a lot of effort. But if any of the above parties would deserve to be listed for the new “World’s Hottest Pepper” in the Guinness World Records, it is undoubtedly the people of Northeastern India who have been cultivating and using this pepper for centuries. And the NMSU Chile Pepper Institute deserves a big applause for once more demonstrating to be the leading organization in capsicum research.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Why Breed such an Ultra-Hot Chile?

I was foolish enough to taste a dried Jolokia pod — right after sensing a somewhat sweet, fruity flavor, it burns like hell. If the Jolokia’s bite is so painful, why did humans create this cultivar? The answer might be that some of the first reports about this pepper were published by the Defense Research Laboratory of India, located in the Assamese garrison town of Tezpur. Obviously this pepper isn’t just meant to kick up a fish curry. In the past, capsicum oleroresin, the chile extract used to make ultra hot sauce and pepper sprays, was often produced from cayenne pods. While only in the five-digit SHU range, cayenne is not as picky about growing conditions as chinense peppers like the Naga Jolokia. There’s a much wider area to grow cayenne, so from an economical standpoint, it makes sense to use cayenne. But with Jolokia being so much higher in capsacin content, it is no wonder that those interested in spraying the burn are also evaluating the Assamese power pod. Fiery-foods.com reader Richard Frost mentioned another use for the highly concentrated heat, stating that the largest consumers (70%-80%) of chile oil in the world were manufacturers of underground and underwater material coatings, being used extensively in the outer layer of underground cables and in boat paint. According to Frontal Agritech though, the Jolokia pepper has a long tradition in India, especially in Assam, Nagaland and Manipur. Literature describes its use in traditional medicine for curing all sorts of ailments. This chile is also commonly used there for making pickles and adding heat to non-vegetarian food items and dishes. With capsaicin content so much higher than in Mexican or Caribbean chiles, I also asked Leena if there were possibly GMO (genetically modified organism) techniques involved in gaining these levels. Leena replied that the existing heat level in Bih Jolokia is inherent, solely maintained by selection at the company’s farms. What they’re doing is purely natural, not by use of any GMOs. In fact, Frontal Agritech’s slogan “Redesigning Agriculture” doesn’t refer to any high-tech approach, but to organizing farms in their area and teaching their owners traditional farming, using organic techniques wherever possible.

Heat isn’t Everything…

OK, so Bih/Bhut/Naga Jolokia is the new champion in the world of heat. But heat isn’t everything. The Assamese growers at Frontal Agritech may be right when pointing out that besides this chile’s genes, the unique soil and climatic conditions of their Northeast-Indian regions contribute its properties, which also includes its flavor. Such environmental influences are best known for wine. For example, the Nero d’Avola grape grows fine in Sicily as well as on Italian mainland – but just growing it in Calabria (southern tip of the boot) results in a different aroma — red wine from this grape is superior when coming from Sicily. Some grape varieties only develop their full potential in Napa Valley, CA, or somewhere else in the world. And in fact, even some chile pepper varieties are tied to geographical regions. If you’ve ever tasted roasted green New Mexican chiles grown in Southern New Mexico, and for comparison the same chile from your backyard, also roasted over propane, you know what I mean. Europe also has some peppers that thrive best in their original microclimates — see our reports about Piment d’Espelette in the Basque district France, or Peperoni de Senise in the Basilicata region of Italy. And while Red Savina quite possibly won’t be “The World’ Hottest” in the future, it will continue to be a blistering-hot pepper that fiery-foods manufacturers turn into great tasting hot sauce and salsa.

* * * UPDATES * * *HOT News from Guinness World Records

February 2007: At the 2007 New Mexico Chile Conference, held on February 5 & 6 in Las Cruces, Dr. Bosland proudly presented a document he recently received from Guinness World Records, Ltd. — the certificate that officially declares Bhut Jolokia the “hottest of all spices.”

Now it’s official!

Worldwide Fame for a Fiery Chile

December 2007: Since Bhut Jolokia’s Guinness World Records entry made worldwide headlines, the “ghost chile” gained incredible popularity. Thanks to the NMSU Chile Pepper Institute’s research (and their PR efforts), the Indian growing regions could enjoy an enormous increase in demand for the now famous pepper. This was more than welcome in a region that has to cope with political instability, high crime rates, a tea industry suffering from falling prices and rising costs, and a large part of the population living below poverty level. A growing business of growing Bhut Jolokia means a lot of new jobs in agriculture, processing and administration. According to an AP report published past summer, one Assamese company shipped barely one ton of the Naga chilis in 2006. For 2007, it looks more like ten tons, exported to nearly a dozen countries around the world. And that’s just one company…

While the predicted “special breeds” like “Moscow Morich” didn’t show up (yet), it looks like India is attempting to patent the pepper that got its fame mostly to the CPI’s merits (and with all due modesty, our SuperSite report most likely helped a little bit as well). Remembering the sometimes ridiculous restrictions and supply shortages that came with Red Savina’s licencing policy, any such patent leaves mixed feelings about this subject.

Backyard Bhuts

Test-growing Bhut & Co.

While we started Naga Morich in the late summer of 2006, we grew our Bhut/ Bih Jolokia test plants in 2007. For results, see also our Jolokia Comparison Report.

Our various Naga test plants did much better than we expected – healty plants, plenty of flowers, and also pollination and fruit set went quite well.

As shown above, Bhut Jolokia produced up to five pods per node. It is also evident that there’s an extreme variation in fruit shape, even on the same plant, and even off the same node. Some pods are slim, others are roundish with wide shoulders. Some have a round tip, while others are tapered, mostly combined with a slim shoulder. Therefore, determining the variety based on the fruit shape is almost impossible. Only the bubbly, uneven surface of the pods seems to be characteristic for this kind of chile.

Our greenhouse came closer to Assam’s warm humid climate – see plants in the left picture above, which did much better than the comparison plants outside – even Southern Germany is definitely not the ideal Nagaland… that’s why we’re getting our Jolokias directly from India.

Whenever Bhut Jolokia made news in print and on the Web, pictures of orange-colored pods were shown. So it came to some surprise that the final mature color of this pepper is a nice deep red. Once the fruits have reached about their final size, they start changing colors, going through a darker green, followed by orange, and eventually red. Even our backyard Bhuts were not only incredibly fiery but also quite flavorful, with a fresh, sweet and fruity aroma, comparable to some Caribbean chinense varieties.

Here’s a Bhut pod cut open. Note the three-chamber contruction. Both the mesocarp and the divider walls are rather thin. This eases drying the pepper, but unless you live in the U.S: Southwest, using a dehydrator is still advisable.

We also observed that Nagas stay fresh much longer than most other peppers. The picture above shows pod above was stored for almost six weeks unrefrigerated, at room temperature. Yet is was almost as crunchy as right after harvesting. It would be interesting if the extremely high capsaicin content plays a role in this. The peppers harvested while not matured to a full red stayed crispy for the longest time. A good deal of the heat is already present in the green pods, just as with habaneros or many other varieties.

But even the superhot Nagas seem to have enemies. On the bitten Bih Jolokia pod above, we think slugs were the culprit, providing a clear view of the seeds.

Commercial growing might be a different story, but keeping a Naga plant at home until the next year can pay off, as evidenced by our Naga Morich plant in its second year. This one, placed in a container on a sunny southern porch, was surprisingly prolific, even if the pods were small. Isn’t that a beautiful sight!

News from the Bhut CampYet another Bhut Record

The pepper made it into Guinness Book of World Records, and 25-year-old Anandita Dutta Tamuli from Jorhat (Assam) is hoping to get into the famous list as well. Anandita grew up with the hot chiles and started eating them from the age of five, so she knows her peppers. Already in the summer of 2006, she proved on TV that she can eat 60 Jolokia pods within two minutes. To top that, she broke open a pod and rubbed her eyes with it, just briefliy blinking afterwards. Ouch! Don’t try that at home. Provided the address didn’t change and the content is still there, check here for the dazzling video footage. This raises the bar for all those bold “chile eating contests”.

“Bhut Bombs Away” — Elephants, beware!

Africa has many elephants, and so does India. And both have the same problem: A growing population means villages and plantations are expanding and moving closer to the giant (and hungry) animals’ territory. Similar to the African Elephant Pepper Project, wildlife experts in Guwahati (North-east India) are now trying to fend off marauding elephants from destroying homes and crops with the help of hot peppers: As part of an experimental project in Assam, they erected jute fences, coated with grease and Bhut Jolokia. To keep out the elephants without harming the animals, they are also using smoke bombs made from the hot chiles — filling straw nests with the hot pods and burning those bombs. Elephants are driven away by the fiery fumes. Famous Chicago Chef jumps on the Bhut Bandwaggon

Links, Sources

Photos Copyright © by Harald Zoschke, except fresh Bhut Jolokia pods on (1) (Paul Bosland) and (2) (Leena Saikia, Frontal Agritech) Red Savina™ is a trademark of GNS Spices

|