Today, almost 130 years later, the star of the fair continues to be the Datil pepper, which is featured in two of the fair’s most beloved dishes: pilau (a delicious rice dish often served with chicken or pork) and—you guessed it—Minorcan seafood chowder. Hundreds of urbanites (who would otherwise probably would never visit the agrarian community) make the trek out to Elkton each March to sit in the shade beneath a gorgeous canopy of Spanish moss-draped oak trees. There they would down heaping plates of Datil-spiked pilau and brimming bowls of fiery Minorcan chowder while tapping their feet to the country tunes of local groups like The Red River Band. It never ceases to amaze me how far people will drive for good food. But the proof is in the chowder—the undersized fair goes through a whopping 130 gallons of it each year.

|

| St. Ambrose Catholic Church, home of the “Chowder Chapel.” |

Mary Ellen Masters, baptized the “Master of the Chowder,” has been in charge of preparing the fair’s supply of soup—served mild, medium, or hot (all relative terms when we’re talking about Datils, of course)—for the last 20 years. She learned the basics of preparing chowder from her mother, then improvised and honed her skill through trial and error.

“I’m not the kind of cook that uses precise measurements—I just cook and taste. When it tastes right, it’s done,” she told me.

Gopher tortoise chowder was on the menu at the fair until the 1950s, but was then replaced by clam chowder for modern palates. When Masters took over chowder duties in the 1980s, she started out making only about 15 gallons for the event. Today, as word of her chowder-making prowess has spread, she prepares almost nine times the amount. She said, “I think we’re at capacity right now and I’m not sure we can make any more than that. Some people get mad if we run out early. This past year, we started serving at noon and we were out of chowder by 1:30. There were a lot of disappointed people that day!”

To help her keep up with increasing demand, her husband and sons built an open air kitchen space they dubbed the “Chowder Chapel” that’s located on the grounds of the old white clapboard church. It takes about a half gallon of Datil peppers to get the taste and spiciness just right when you are making 130 gallons of chowder; Masters and her husband grow and freeze their own Datils for the event each year. Masters told me that she puts Datils on or in “just about everything—cornbread, deviled eggs, baked potatoes, you name it.” But her signature dish is definitely her chowder and the fair is her showcase.

“You know, my family has a long history with the fair. My great-grandparents were the first couple married at the parish and I’ve been attending services there since I was born. My mom always helped with the fair and then she passed the torch to me, and now my own daughter helps me out. I’m hoping she will eventually take over…this is a tradition. There are people I only see once a year, but they come back year after year, and it’s like one big family.” Indeed, for many in the area, the Datil is a bond that connects people to the past and gives them a sense of place.

Just down the road from Elkton, in the tiny town of Hastings, an agricultural center that produces more potatoes and cabbage than any other locale in Florida, charismatic restaurant owner John Barnes can get you your Datil fix any day you’d like. His popular eatery, Johnny’s Kitchen, bursts at the seams with customers daily and many of his most soul-satisfying dishes owe their tang to his affection for Datil peppers. This is good, solid Southern

|

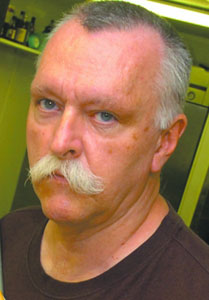

| Johnny Barnes |

food—nothing fancy—just time-honored dishes prepared with the freshest ingredients like your grandma would make. In this case, it’s Barnes’ own grandmother, now deceased, who inspires his cooking.

“My grandma was what I call a real country lady—she cooked every day, she could butcher a hog, make her own sausage—she would leave a pot of beans cooking all day and go hand-wash some laundry. You never knew how many people might show up, so she always had plenty of food ready,” Barnes told me. “People just don’t have the time to simmer collard greens for hours like they used to, so now I do it for them. My customers want the food from their childhoods. I mean, I had never eaten anything canned or processed until I joined the Navy and it was a shock to my system! There was a time not so long ago when we ate local foods according to the seasons and that’s what I do here,” said Barnes.

“Each afternoon I shop at the County Line Produce Stand and pick out my vegetables. Then I head to the San Mateo Butcher Shop and watch them cut my pork chops by hand. I buy whatever I see is freshest and cook it the next morning. And when we run out, we’re done.” For many of Barnes’ customers, that took some getting used to, as people were not too pleased about arriving at the restaurant only to find that they were out of fried chicken or fish. “I don’t buy frozen. Who wants old fish? I had to convince people that’s the way it was gonna be. When we’re done, we’re done,” he continued.

Barnes has been the catalyst for a mini-Renaissance taking place in Hastings recently, which was first established as a farm town to feed the wealthy Northern snowbirds like oil and railroad tycoon Henry Flagler, who wintered in St. Augustine in the early 1900s. Back in the day, Elmo’s Drugstore was the place to see and be seen in Hastings. It was where farmers commiserated over poor planting weather and youngsters hung out after school. It was the place to chat and gossip and catch up with your neighbors. Slowly, the forces and pressures of modernity began altering the community over the decades—downtown’s once-bustling Main Street was nearly abandoned; many proud families left farming and left the town altogether seeking better-paying jobs and new opportunities elsewhere. Elmo’s was forced to close its doors.