In support of defendant’s contention that, if McIlhenny originally had a trade-mark right in the name “Tabasco,” it was lost when his patent for the manufacture of pepper sauce, taken out in 1870 expired, the leading case relied on is Singer Manufacturing Company v. June Mfg. Co., 168 U. S. 169, wherein it was held that, on the expiration of a patent, the public has the right, not only to make the patented article, but to use the identifying name it came to be known by with the acquiescence of the patentee during the term of the patent. The facts, however, in the present case make the Singer case inapplicable. McIlhenny continued to make his sauce by the process and with all the ingredients described in the patent only for about five or six years, since which time he and his successors have eliminated several of the ingredients and have manufactured the sauce simply “by mixing crushed pepper pulp with vinegar and salt.” During the short time McIlhenny manufactured the sauce under the patent, his business was very small and of little consequence. The marked growth of the business has been during later years, long after the abandonment of the patent. The word “Tabasco” has been in actual use since such abandonment of the patent to describe a sauce which was not made by the patented process. The Court of Appeals in the Gaidry case said:

“If Edmund Mcllhenny, prior to the expiration of the patent to him, had acquired the exclusive right to use the word ‘Tabasco’ with reference to a sauce not made by the patented process, that right was not extinguished by the expiration of the patent, as the patent had nothing to do with the acquisition of it. The expiration of the patent did not have the effect of conferring on the public, or the plaintiff as a part of it, any right with reference to the name of the thing which was not a subject of the patent.”

Defendant Bulliard, concededly, has a perfect right, so far as plaintiff is concerned, to make sauce in accordance with the patent, but he does not pretend to be doing so, and, in fact, since the adoption of the National Prohibition Amendment to the Constitution and the passage of an enforcement statute by Congress, he may not do so, as the patented process provided for a mixture of alcohol as well as vinegar with the pepper pulp. This then, is not the case of a manufacturer, after the expiration of a patent, availing himself of the right to make the identical article patented and claiming the right to identify it by the name given to it by the inventor, or acquired by it as identifying the patented article. What the defendant desires is not the right to the use of the process, to which plaintiff makes no objection, but the right to the use of the name to designate a sauce not made in accordance with the patented process. Ordinarily the name is but an incident, a matter of but secondary importance to the substance of the thing patented, but in this case the name is of great commercial value, whereas the patented process, long since abandoned, is absolutely worthless.

Even had McIlhenny not abandoned his patent but continued to use the patented process, it does not necessarily follow that the defendant, on the expiration of the patent, would have had the right to give to a sauce manufactured by him by the patented process, the name “Tabasco.” In Hopkins on Trade-Marks, 2nd Ed., page 80, after a statement of the general rule that the right to use the name passes to the public with the dedication resulting from the expiration of the patent, it is added—

“There seems to be an exception to this general rule where the use of the name antedated the existence of the patent, and where it further appears that the name and not the patent gave its value to the article.”

See Thompson v. Batcheller, 98 Fed. 660; President Suspender Co. v. McWilliams, 288 Fed. 159 [7 T. M. Rep. 108]; Searchlight Gas Company v. Prest-o-lite Co., 215 Fed. 692 [4 T. M. Rep. 278]. The use of the name “Tabasco” preceded the patent by about two years, and, as similar sauces with the same ingredients have for many years been on the market, it is clear that it was the name and the intrinsic merit of the article, rather than the patent, which gave the sauce its value.

The conclusion of the Court is that plaintiff’s predecessor originally acquired a valid trade-mark in the word “Tabasco” as applied to pepper sauce, and that, by no action or inaction during the subsequent years, has plaintiff lost the resultant right to its exclusive use. The use of the same word by defendant to designate his sauce constitutes an infringement of plaintiff’s trade-mark, but, in view of the ruling of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and of the Supreme Court of Louisiana, in the cases heretofore noted, such bad faith cannot be ascribed to defendant in the use of the word as would warrant an award of damages against him.

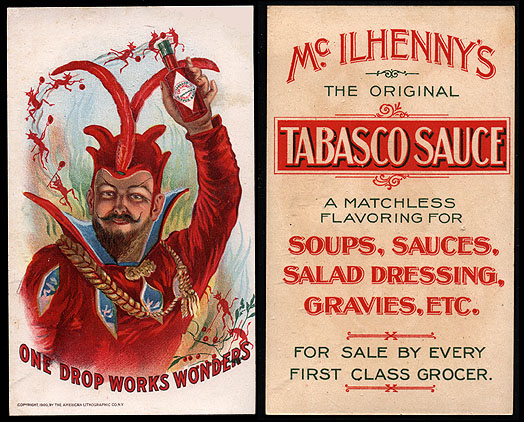

The plaintiff further is entitled to relief on its claim of unfair competition—in addition to violation of its trade-mark—in that the sauce manufactured by the defendant is intentionally so bottled and packaged as to be easily mistaken for that of plaintiff. Such close resemblance in the dressing of the two products, I must conclude, was by design rather than by accident. At the time defendant began his manufacture of the sauce in 1916, the label then in use on plaintiff’s bottle contained the following printed matter:

“Caution: This sauce should always be mixed with your gravy, vinegar, or other condiment, before using. One or two drops are enough for a plate of soup, meat, oysters, etc., etc.

“It is superior in flavor to, and cheaper than any similar preparation; one bottle being equal to a dozen of the ordinary kind. Established 1868.

“Use only McIlhenny’s, the original and genuine.”

The first paragraph of the caution was copied verbatim by the defendant on his labels, and for the second paragraph, was substituted: “It is superior in flavor to any similar preparation.” The last line, “Use only McIlhenny’s the original and genuine,” was changed to read: “Use only the genuine Evangeline, put up by Ed. Bulliard, St. Martinville, La.”