The directions for use then printed on the McIlhenny carton were likewise copied at length and verbatim on the Bulliard package. Defendant in explanation states that he did not intend to have his carton printed in imitation of complainant’s, but that, in ordering said cartons, he sent with the sample a slip containing words that he desired placed on his own cartons, which the printer misunderstood, and, instead, copied thereon the printed matter on the McIlhenny carton “sent as a guide for shape and size.” He admits, however, that the printed matter on the label of the McIlhenny bottle was printed as ordered, but states that such labels and such cartons were used for only about a month. Neither plaintiff nor defendant, it appears, has used this printed matter during the past two or three years.

It appears from defendant’s own statement, that the McIlhenny bottle and carton were used as a guide in the manufacture of his own, and the inference must follow that his intention then was to make it appear to the casual observer that his sauce and that of plaintiff were one and the same, and thus secure the advantage of the extensive advertisement and wide demand for plaintiff’s product, which the stipulation shows is sold in every State of the Union and many foreign countries and is handled by a large maj ority of the jobbers in the United States.

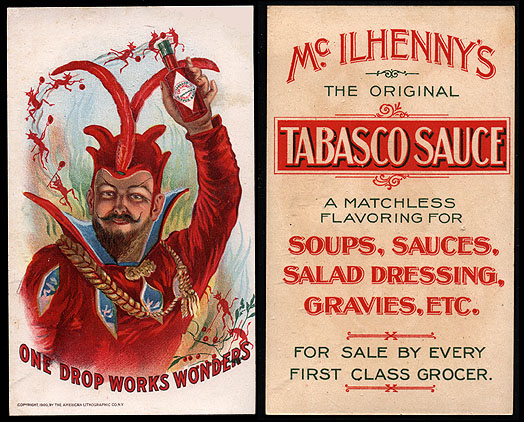

Not only was the printed matter on the McIlhenny bottle and carton copied, but defendant adopted a bottle and carton of the same size and shape and strikingly similar to that of plaintiff. During the past few months the shape of the defendant’s bottle has been changed from round to polygonal—so slight a change as not to be readily noticeable. Defendant’s bottles, like those of plaintiff, now in use, are small and slender, with long neck, filled with a red liquid, and provided with a sprinkler or dropper. Placed side by side, there are differences easily discernible which would not, however, be readily noted by the average purchaser seeing the respective bottles on different occasions, the chief distinguishing mark of defendant’s being a picture of a live oak tree with a blue background and the word “Evangeline” preceding “Tabasco Sauce.” There is also a difference in the color of the lead foil on the mouth of the bottles, but it is a difference which would not likely be noticed unless called to the attention of the prospective purchaser. The general appearance, the ensemble, is so similar that it is apparent that the Bulliard product may easily be mistaken for that of McIlhenny’s.

The policy of the law favors competition as “the life of trade,” but it insists that it be fair. Unfair competition discourages the incentive to superior workmanship and robs the honest trader of the just reward of his skill and industry. It permits the unscrupulous dealer to deceive the public and to profit by the sale of a spurious article in the dress of a well known and popular brand. In justice to the established business of the manufacturer, and in protection of the rights of the public, the law places the stamp of its disapproval on such business methods. No man should be permitted to put his goods on the market in another’s livery, but, where the same articles are manufactured by competitors, the product of each should be so presented as to be readily recognizable as the handicraft of its maker. It should stand on its own merits and gain its way to popular favor by its own inherent quality.

With the expansion of commerce, there has been developed in recent years a well defined jurisprudence in cases of this character, involving what has come to be known as unfair competition. The doctrine, now well recognized, both by the English and American Courts, is thus well expressed by the Lord Chancellor in Powell v. Birmingham Vinegar Brewery (1897), A. C. 710, 14 R. P. C. 720, 727:

“The proposition of law is one which, I think, has been accepted by the highest judicial authority, and acted upon for a great number of years. It is that of Lord Justice Turner, who says, in terms: ‘No man can have any right to represent his goods as the goods of another person. In an application of this kind, it must be made out that the defendant is selling his own goods as the goods of another.’ That is the only question of law which, as it appears to me, can arise in these cases. All the rest are questions of fact. The most obvious way in which a man would be infringing the rule laid down by Lord Justice Turner is if he were to say in terms, These are the goods manufactured by’ a rival tradesman; and it seems to be assumed that unless he says something equivalent to that no action will lie. It appears to me that that is an entire delusion. By the course of trade, by the existence and technology of trade, and by the mode in which

things are sold, a man may utter that same proposition, but in different words and without using the name. By the identity of the form of the bottle or the form of the label, or the nature of the thing sold in the package, he is making the statement not in express words, but in one of those different forms in which the statement can be made by something that he knows will be so understood by the public. In each case it comes to be a question whether or not there is the statement made and if the statement is made, there can be no doubt of the legal conclusion that he must be restrained from representing that the goods he makes are the goods of the rival tradesman. Then you get back to the proposition which I have read from Lord Justice Turner.”

And in the case of MacLean v. Fleming, 96 U. S. 245, the

Supreme Court thus succinctly upholds the doctrine:

“The latter has obtained celebrity in his manufacture; he is entitled to all the advantages of that celebrity, whether resulting from the greater demand for his goods or from the higher price the public are willing to give for the article, rather than for the goods of the other manufacturer, whose reputation is not so high as a manufacturer.”

See also New England Awl & Needle Company v. Marlboro Awl & Needle Co., 168 Mass. 154, 46 N. E. 886.

Not only did defendant adopt the name and imitate the bottles and cartons in use by plaintiff, but at the very beginning, when he started the manufacture and sale of his sauce in competition with the long established business of plaintiff, he printed on his bottle labels a caution to use “only the genuine Evangeline,” thus apparently seeking to create the impression that such “Evangeline” Tabasco Sauce was an old and established brand, against spurious imitations of which the public should be warned. These facts and circumstances lead to the conclusion that defendant’s effort was to so imitate the bottling and packaging of plaintiff’s sauce as to readily deceive the unobservant consumer, while yet preserving a sufficient distinction between the two. as would permit the building up of a demand from dealers for his own product.

Of course, there are differences in the appearance of the respective bottles, and of the respective cartons, but they are what Judge Lacombe in Scheuer v. Muller, 74 Fed. 225, 228, calls “arguable differences”; and, what was said by Judge Lurton in Paris Medicine Co. v. Hill, 102 Fed. 148, 150, may be said in this case, “the differences are less observable than the resemblances.” And when, on the similar appearing bottles and packages, there is printed the name “Tabasco,” defendant’s product is well calculated to deceive the average user of the sauce, who is not expected to remember more than the general features of a mark, brand or label, (Little v. Kellum, 100 Fed. 858, 854; Cantrell v. Butler, 124 Fed. 290; Kosterling v. Seattle Brewing Co., 116 Fed. 620; Scriven v. North, 184 Fed. 866, 878), and is not supposed to know that imitations exist (Wellman v. Ware, 46 Fed. 289).

The fact that defendant has not only dressed his product in imitation of that of the plaintiff, but has, in addition, likewise used plaintiff’s trade-mark, gives added reason why the Court should require that hereafter defendant not only discontinue the use of the name “Tabasco,” but that he adopt a new and distinctive bottle and carton, such as will clearly and unmistakably differentiate his sauce from the “Tabasco Pepper Sauce” manufactured by plaintiff. Defendant may thus place himself in a position to in turn claim the protection of the law, should others thereafter attempt to infringe his trade-mark or to imitate the dressing and packaging of his product.

A decree will be entered in accordance with the prayer of plaintiff’s petition, enjoining the defendant from using or employing in connection with the manufacture, bottling, and packaging, advertisement and sale of his sauce, the word “Tabasco,” and from using or employing in connection with such manufacture, advertisement and sale of such sauce, bottles, wrappers, cartons, or packages, like those shown in the exhibits herein filed, or so resembling those of plaintiff as to be calculated to induce the belief that such sauce is that manufactured by plaintiff.

[note: For related case see McIlhenny Co. v. John, Sexton & Co., 10 T. M. Rep. 175.]