Editor’s Note: From the Ortega website: “It all started with chile peppers. Emilio Ortega’s fascination with chiles began when he moved to New Mexico in 1890. Here he encountered the state’s popular big red chiles. Emilio discovered he preferred this chile when it was still young and green because it was tender and mild in flavor. When he returned home to California a few years later, he brought with him chile pepper seeds and many recipes for dishes he had grown to love while in New Mexico. Back home with his family at their adobe house in Ventura, California, Emilio planted the chile seeds. Those chiles grew extremely well in the temperature climate of Ventura. Soon Emilio had so many chiles he had to give them away. Everyone loved them! That’s when he knew he had something special. Emilio learned that if the green chiles were roasted, peeled, seeded and washed, they could be preserved in jars for some time. But since glass was difficult to handle, Emilio worked out a way to use cans instead. He founded the Ortega Chile Packaging Company; the first commercial food operation in the state of California!”

Editor’s Note: From the Ortega website: “It all started with chile peppers. Emilio Ortega’s fascination with chiles began when he moved to New Mexico in 1890. Here he encountered the state’s popular big red chiles. Emilio discovered he preferred this chile when it was still young and green because it was tender and mild in flavor. When he returned home to California a few years later, he brought with him chile pepper seeds and many recipes for dishes he had grown to love while in New Mexico. Back home with his family at their adobe house in Ventura, California, Emilio planted the chile seeds. Those chiles grew extremely well in the temperature climate of Ventura. Soon Emilio had so many chiles he had to give them away. Everyone loved them! That’s when he knew he had something special. Emilio learned that if the green chiles were roasted, peeled, seeded and washed, they could be preserved in jars for some time. But since glass was difficult to handle, Emilio worked out a way to use cans instead. He founded the Ortega Chile Packaging Company; the first commercial food operation in the state of California!”

The article in Sunset, 1901:

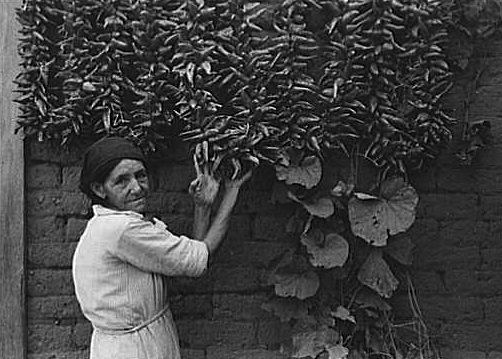

THE chili pepper is a hot product of this semi-tropic land, and is a link between the California of today and its Spanish occupation. Find a gray old adobe in the outskirts of a California town, or in some sequestered nook in the hills, and in the season its walls will be aflame with strings of red peppers drying in the sun. Under the low eaves and quite around the house they will hang in triple rows, in delicious contrast with the rich adobe gray. Given, now, a handsome señorita, with fine oval face and large, soft eyes, and broad, low brow and a strain of pure Castilian blood, to show red-warm through olive cheeks, a white kerchief over her bosom, and a glimpse of amber or gold beads about her throat, and the low, gray, wide-roofed adobe, scarlet-hued with festoons of red peppers, the whole seen against the burnt umber or yellow of the hills and under the pearly haze of a morning in September, and you have a grouping of such splendid color as would delight the heart of a painter.

But we are interested now, not in the aesthetics of the subject, but in its commercial aspects. Here is one of the minor industries of the state, so modest and inconspicuous as to pass almost unnoticed. Recently, in one of our sea-girt towns, in an old Mexican house with wavy, tile-covered roof and ruined wing, and rough, modern annex of boards, we found a chili factory, without a signboard or placard, presided over by a low-voiced Mexican, very busy but not forgetful of courtesy. Inside, we found two stalwart young men and the señora — a Spanish family canning a Spanish product of the brown soil, the green chili peppers. A rude furnace of brick, home-made, for steaming the cans, another holding the vast kettle in which the “hot stuff” was cooking, the soldering-iron at work closing up the cans, and the labels going on, while the air was pungent with pepper. This was a family day in the little factory, evidently, for in all its work Señor Ortega employs about fifty men.

We do not need to describe the process of canning green chilis — it is simple. The little industry is but a year old, yet its product was two thousand cases, of six dozen to the case, and will be double that this year, as by this time the humble plant is enlarged and  transferred to Los Angeles and established in better quarters, with a well known firm to see to the marketing of its output. The demand at present for this hot appetizer is in the Southwest, but is steadily extending to all parts of the country.

transferred to Los Angeles and established in better quarters, with a well known firm to see to the marketing of its output. The demand at present for this hot appetizer is in the Southwest, but is steadily extending to all parts of the country.

The cultivation of the pepper has long been desultory, carried on chiefly by the Spanish-Mexican population, in small patches. But now the increasing demand in the market for both the green and dried article is attracting the attention of farmers who have an eye for crops that do not fail and that yield good returns. Until recent years, this product has been marketed chiefly in its dried state, and carloads of dried chilis are imported from Mexico to supply the coast trade. Curiously, a considerable percentage is shipped back as far as Arizona and New Mexico, for it is there and in Colorado and Texas that the chief market for the chili is at present found. But its use is steadily increasing among the American and English population. While much is shipped from Mexico, its production in California is mounting up and will shortly attain considerable commercial importance. The plant is grown from seed in rows, about three feet apart. After the peppers begin to ripen, they are picked about once a week and allowed to lie a day or two in the sun, then strung on strings and hung up to cure. Many growers prefer evaporating houses to sun-drying, and at a temperature of about 110°, the pans can be refilled about every four days.

With favorable conditions the chili will yield from 7 to 10 tons per acre, and the price ranges from $20 to $25 per ton in quantities, and higher for small lots. Dried, the yield in favorable seasons has been as high as 2400 pounds per acre, and evaporated commands from 10 to 12 cents per pound.

From Sunset, Volume 6, Passenger Dept., Southern Pacific Co., 1901.