By Hubert Howe Bancroft, 1887

In preparing and cooking their food, the Aztecs displayed their usual ingenuity, though many of their dishes were of a very simple character. Maize, or Indian corn, when in the milk, was eaten boiled; when dry, it was parched or roasted, though it usually came to table in the shape of tortillas, then, as now, the staple food of all Spanish America. What poi is to the Hawaiian, what rice is to the Hindoo, and what bread is to most civilized nations, the tortilla was and is to the inhabitants of Mexico.

In preparing and cooking their food, the Aztecs displayed their usual ingenuity, though many of their dishes were of a very simple character. Maize, or Indian corn, when in the milk, was eaten boiled; when dry, it was parched or roasted, though it usually came to table in the shape of tortillas, then, as now, the staple food of all Spanish America. What poi is to the Hawaiian, what rice is to the Hindoo, and what bread is to most civilized nations, the tortilla was and is to the inhabitants of Mexico.

In making tortillas, the Nahuas boiled their maize in water, to which lime, or sometimes nitre, was added. When thus softened, it was crushed with a stone roller, and the dough, after being kneaded, was shaped into tbin round cakes, which were baked in earthen pans, and piled one on another, so as to retain their warmth, for when cold they lost their savor. Several kinds of bread were prepared from maize, some of them, as the tlaxcalli, being in the form of larger and thicker cakes, and some in the shape of balls, as rice is now often served with curry or other seasoned dishes. Atolli, a preparation of maize varying in consistence from gruel to mush, and used both as liquid or solid food, was made of corn, stripped of the husk, mashed, mixed with water, boiled down as required, and sweetened or seasoned according to taste, with honey, chile, or saltpetre.

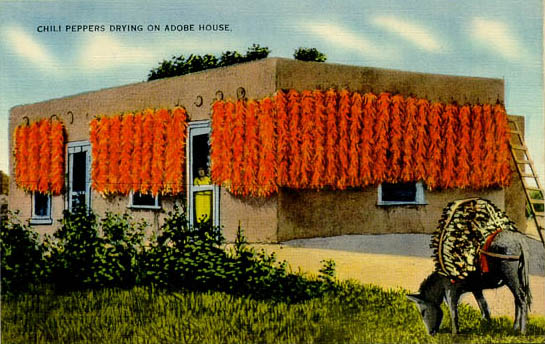

Beans, the etl of the Aztecs, and the principal ingredient in the frijoles of the Spaniards, were boiled, when green, in the pod, and when dry were also boiled. Chilli, chile, or pepper was eaten raw, whether green or dry, and a sauce made from it formed a part of the seasoning of almost every Nahua dish.

Fish, and fowl, fresh or salted, were roasted, stewed, and boiled with dog-fat, and seasoned with chile and tomatl, or tomatoes. Fruits were, for the most part, eaten raw; but some, as the plantain and banana, were roasted or stewed.

Among miscellaneous articles of food may be mentioned the ant, maguey-worm, and the fly of the Mexican lake, which were dried, ground, boiled, and eaten in the form of cakes. There were also eggs of turkeys, iguanas, and turtles, roasted, boiled, and in omelettes; reptiles of various kinds; shrimps, sardines, and crabs; wild amaranth seeds and tule roots; honey of bees, of maize, and of the maguey, and portions of maguey stalks and leaves, which were eaten roasted. All articles of food, whether cooked or uncooked, were offered for sale in the market-places of the larger towns, and near them were eating-houses, where the delicacies and substantial fare of the Nahua cuisine were served up to their patrons.

The Nahuas appear to have restricted their indulgence in rich and highly seasoned dishes to festive occasions, and at their homes to have contented themselves with the plainest fare. The poorer classes had in their houses no cooking utensils, except a hollowed stone, called metate, for grinding maize, and a few earthen dishes for cooking tortillas and frijoles. They ate thrice a day, at morning, noon, and nightfall, using the ground for table, table-cloth, napkin, and chair, conveying their food to the mouth with their fingers, and drinking only water or atole. The repasts of the rich, however, were served on palm-mats, often richly decorated, and napkins and low seats were provided for their use.

The fondness of the Aztecs for feasts and amusements appears to have extended through all ranks of society. Everyman feasted his neighbor, and was himself feasted in turn. From the king to the peasant, each one endeavored to excel his equals in the splendor of his banquets, and as these involved the distribution of costly presents among the guests, it often happened that the host ruined himself by his hospitality. It is even said that many sold themselves into slavery, in order to procure the means for a single feast, whereby their memory would be immortalized.

The grandeur of the feast depended, of course, on the wealth of the host, the rank of the guests, and the importance of the occasion. Those who were invited received, on their arrival, a bouquet of flowers as a token of welcome, and persons of a rank superior to the host were saluted, after the Aztec fashion, by touching the hand to the earth, and then carrying it to the lips. On some occasions, garlands were placed upon the heads of the guests, and strings of roses around their necks, while copal was burned before those whom the host desired specially to honor. While waiting for the meal, they employed their time in strolling through the grounds, and admiring their beautiful shrubbery, green grass-plats, well-kept flower-beds, and sparkling fountains.

When dinner was announced, all took their seats, according to age and rank, on mats or stools, placed close against the walls. Servants then entered with water and towels, with which each guest cleansed his hands and mouth. Pipes, or rather smoking-canes, were then presented in order, as was supposed, to stimulate the appetite. The viands, kept warm by chafing-dishes, were then brought in on artistically worked plates of gold, silver, tortoise-shell, or earthenware, and each person, before beginning to eat, threw a small piece of food into a lighted brazier, as an offering to the god of fire. Many highly seasoned dishes of meat and fish were partaken of, and when the tables were cleared, the servants, in company with the attendants of the guests, feasted on the remains of the banquet. Chocolate was then handed round, together with water for washing the hands and rinsing the mouth. The smoking-canes were again introduced, and while the guests reclined upon their mats, the music suddenly struck up, and the young people, or perhaps some professionals, executed a dance, singing at the same time an ode prepared for the occasion. Professional jesters amused the audience with their jokes, sometimes appearing disguised as foreigners, whose dialect and peculiarities they imitated, and at other times mimicking old women, or well-known and eccentric individuals. The banquet usually lasted till midnight, and when the party broke up each guest received at parting presents of dresses, gourds, cacao-beans, flowers, or articles of food.

From: A Popular History of the Mexican People, by Hubert Howe Bancroft. New York: The History Company, 1887.