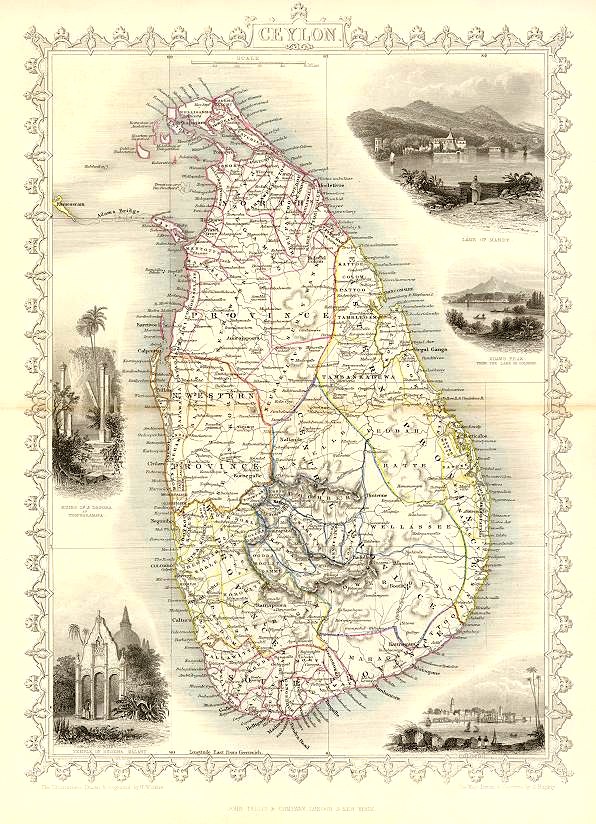

Observations on the Cuisine of Ceylon, by James Emerson Tennent, 1860

The domestic economy of the great body of the Singhalese, who inhabit Colombo and the other towns of the island, is of the simplest and most inexpensive character. In a climate, whose chief requirement is protection from heat, their dwellings are as little encumbered with furniture as their persons with dress; and the coolness of the earthen floor renders it preferable to a bed. Two articles furnish the basis of their cookery–rice and the flesh of the coco-nut. Appasl (cakes made of the former) supply their morning repast, with a scanty allowance of coffee; and curries, in all their endless variety, furnish their afternoon meal.

The domestic economy of the great body of the Singhalese, who inhabit Colombo and the other towns of the island, is of the simplest and most inexpensive character. In a climate, whose chief requirement is protection from heat, their dwellings are as little encumbered with furniture as their persons with dress; and the coolness of the earthen floor renders it preferable to a bed. Two articles furnish the basis of their cookery–rice and the flesh of the coco-nut. Appasl (cakes made of the former) supply their morning repast, with a scanty allowance of coffee; and curries, in all their endless variety, furnish their afternoon meal.

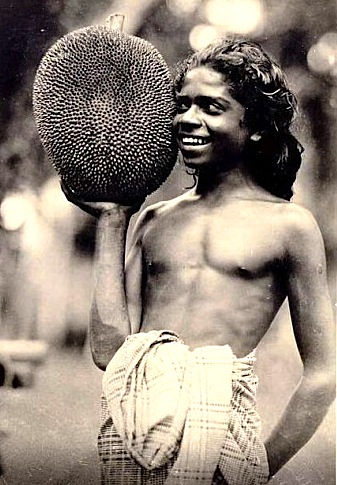

But the residences of the headmen are of a very different class, and exhibit European taste engrafted on Singhalese customs. A dinner at which my family were received by the Maha Modliar de Sarem, the Chief of highest rank in the maritime provinces, was one of the most refined entertainments at which it was our good fortune to be present in Ceylon; the furniture of his reception-rooms was of ebony richly carved, and his plate, chiefly made by native artists, was a model of superior chasing on silver. The repast, besides pastry and dessert, consisted of upwards of forty dishes; and, amongst other triumphs of the native cuisine, were some singular, but by no means inelegant, chefs-d’oeuvre: brinjals [eggplants] boiled, and stuffed with savoury meats, but exhibiting ripe and undressed fruit, growing on the same branch, and bread-fruit, baked and seasoned with the green leaves and flowers, fresh and uninjured by the fire.

But the residences of the headmen are of a very different class, and exhibit European taste engrafted on Singhalese customs. A dinner at which my family were received by the Maha Modliar de Sarem, the Chief of highest rank in the maritime provinces, was one of the most refined entertainments at which it was our good fortune to be present in Ceylon; the furniture of his reception-rooms was of ebony richly carved, and his plate, chiefly made by native artists, was a model of superior chasing on silver. The repast, besides pastry and dessert, consisted of upwards of forty dishes; and, amongst other triumphs of the native cuisine, were some singular, but by no means inelegant, chefs-d’oeuvre: brinjals [eggplants] boiled, and stuffed with savoury meats, but exhibiting ripe and undressed fruit, growing on the same branch, and bread-fruit, baked and seasoned with the green leaves and flowers, fresh and uninjured by the fire.

Cattle are abundant, and especially buffaloes, which are universally employed for tillage; and amongst the objects of cultivation to which the climate is adapted are Indian corn, millet, yams, potatoes, and cassava. Large quantities of materials are grown for the preparation of curry; turmeric, capsicums, onions and garlic, as well as cardamoms and pepper. Large spaces in the forest of two and three hundred acres suddenly appeared cleared of the timber, and enclosed by rustic fences, with a few temporary huts run up in the centre, and all the surrounding area divided into patches of Indian corn, coracan, gram, and dry paddi: with plots of esculents and curry stuffs of every variety, onions, chillies,* yams, cassava, and sweet potatoes.

The articles raised by this species of garden cultivation are of infinite variety. Every field is carefully fenced in with paling formed of the mid-ribs of the palmyra-leaf, or by rows of prickly plants, aloes, cactus, euphorbias, and others; and every one is divided into small beds, each containing a different crop; but the most frequent and valuable crops are the ingredients for the preparation of curry; such as onions and chilies, which are exported to all parts of the coast and carried in large quantities into the interior. Along with these, are turmeric, ginger, pumpkins, brinjals, gourds, melons, yams, sweet-potatoes, keere (or country cabbage), arrow-root, and gram.

The articles raised by this species of garden cultivation are of infinite variety. Every field is carefully fenced in with paling formed of the mid-ribs of the palmyra-leaf, or by rows of prickly plants, aloes, cactus, euphorbias, and others; and every one is divided into small beds, each containing a different crop; but the most frequent and valuable crops are the ingredients for the preparation of curry; such as onions and chilies, which are exported to all parts of the coast and carried in large quantities into the interior. Along with these, are turmeric, ginger, pumpkins, brinjals, gourds, melons, yams, sweet-potatoes, keere (or country cabbage), arrow-root, and gram.

I have shown the error of the belief prevalent amongst Europeans, that the use of curry was introduced by the Portuguese, and that the word itself is derived from that language. In addition to the evidence there stated, it may be mentioned that Ibn Batuta, two hundred years before the Portuguese had appeared in the Indian Seas, describes the natives of Ceylon eating curry, which he calls in Arabic couchan, off the leaves of the plantains, precisely as they do at the present day: “They also brought banana leaves on which they placed the rice that forms their food. They spread the rice with couchan [curry]…consisting of chicken, meat, fish, and vegetables. “

* In Singhalese, dry red chiles are cotchi kale and fresh green chiles are patcha kotchi kale.

Source: Ceylon: An account of the island. Volume 2, by James Emerson Tennent. London: Longman, 1860.