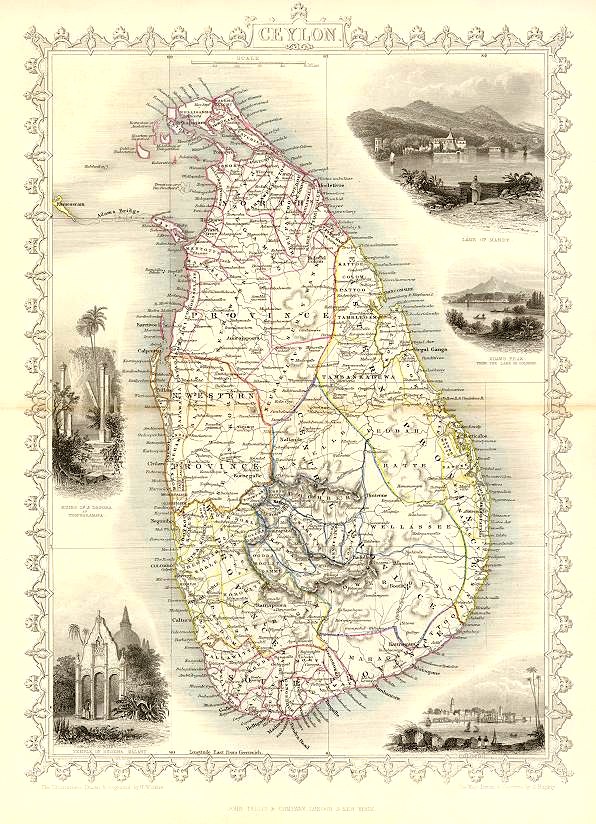

On the Ingredients of Ceylon Curries, by Horatio John Sucklin, 1876

Ceylon curries are much superior to those of India, from their mixing cocoa-nut milk with them, which is obtained by grating the kernel into a pulp, and pouring boiling water on it, the liquid resembling cow’s milk. Curry and rice is a very ancient dish, being mentioned in the “Rajavali” in the second century B.c., and in the “Mahawanso” in the fifth century A.d. The origin of the English term curry is not quite clear; it has no resemblance to the name for the dish in any language in India or Malay: in Hindu it is called sailan.

Ceylon curries are much superior to those of India, from their mixing cocoa-nut milk with them, which is obtained by grating the kernel into a pulp, and pouring boiling water on it, the liquid resembling cow’s milk. Curry and rice is a very ancient dish, being mentioned in the “Rajavali” in the second century B.c., and in the “Mahawanso” in the fifth century A.d. The origin of the English term curry is not quite clear; it has no resemblance to the name for the dish in any language in India or Malay: in Hindu it is called sailan.

The markets of Ceylon are supplied with many fine fish known in Europe —soles, mackerel, dories, and red mullet, besides those peculiar to Indian seas. There are an abundance of very large prawns generally made into curry; and a small sardine, which the cooks string together by the dozen on fine wooden skewers, and then fry them. The seer, usually cut in slices and boiled, is the best fish in the island.

Poultry are good and were cheap in Ceylon, a fine fowl being had for six fanams, or ninepence; geese, turkeys, and ducks are equally moderate, but ducks are in bad repute in consequence of their dirty habits in feeding, the natives allowing them to pick up any filth about their huts, where they are reared. Ceylon geese are very small, of a dark brown colour with black bills, having a large horny protuberance on them. There are also guinea-fowl, pea-fowl, muscovy ducks, and several species of pigeons from Persia and Arabia. Some of the fowls have black bones, and are called “kalu maskulalo” by the natives; and Malabar fowls (Gallus bankiva), their plumage is a sooty-grey, aptly described as looking like a white fowl dragged down a chimney. The skin and inside of the mouth has also a dark appearance. Some persons think their flavour superior to those with white bones. There is one in the British Museum.

Poultry is the chief food of the Europeans, butchers’ meat, except pork, being generally execrable. Pigs of the Chinese breed are very numerous in Ceylon, and thrive well, as they do in all hot climates. Beef is so tough, cooks pound steaks on flat stones before cooking. The best sheep in the island are reared about Jaffna, where there is some pasturage among the swampy islands, and Jaffna mutton, which is tolerable, is sometimes obtainable at Colombo; but the ordinary mutton or lamb is in reality goat or kid, there being great numbers of these animals about native houses and verandahs in the Pettah. Jaffna sheep are exceedingly small, having hair instead of wool, and a horny covering on their knees, caused by a peculiar habit of kneeling down when eating short herbage.

Source: Ceylon: a general description of the island, historical, physical, statistical, Volume 1, by John Sucklin. London: Chapman & Hall, 1876

Bombay Duck and Drumstick, by Walter J. Clutterbuck, 1891.

The curry in Ceylon is a very different dish to one of the same name in England. Curry here means a course, and a very big course, to itself. You are handed first rice, which is small and exceedingly dry compared with what you generally get at home; then follow three sorts of curry—vegetable, fish, and meat. After this a man comes round with a nasty sort of dried-up fish, called ‘Bombay duck,’ and a round thin wafer biscuit, which you are intended to pound up in your rice. Lastly, there are two kinds of ‘sambal,’ which is the heating part of the curry, and which you add to your liking, as the curries are not hot in themselves.

The curry in Ceylon is a very different dish to one of the same name in England. Curry here means a course, and a very big course, to itself. You are handed first rice, which is small and exceedingly dry compared with what you generally get at home; then follow three sorts of curry—vegetable, fish, and meat. After this a man comes round with a nasty sort of dried-up fish, called ‘Bombay duck,’ and a round thin wafer biscuit, which you are intended to pound up in your rice. Lastly, there are two kinds of ‘sambal,’ which is the heating part of the curry, and which you add to your liking, as the curries are not hot in themselves.

In the hills of Ceylon they make a curry called ‘Drum-stick.’ This is a vegetable curry composed of the pods of a long thin sort of bean, the shell of which is much too stringy to eat, but the beans and flesh inside the pods are really first-rate. The meat in Ceylon is generally too tough to be good, but you can with safety make your meal off curry and fish, as the fish, although not equal to what you get in Europe, is excellent if well cooked.

Source: About Ceylon and Borneo: being an account of two visits to Ceylon, one to Borneo, and how we fell out on our homeward journey, by Walter J. Clutterbuck. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1891.

Recipe for Economical Curry Paste, from Daniel Sanitagoe, General Servant, 1889

Curries can be made from anything, if you could procure the proper Curry Powders, etc. But I myself and several parties who have visited India will be glad to recommend Madras Curries as best; and Ceylon Singhalese Curry (yellow) is good, made of cocoanut juice, Maldive fish, lemon, Curry leaves, saffron, etc. A small girl of 10 years of age will make a Curry, as Curries are easily made in India and Ceylon.

1 pound coriander seed

1/4 pound dry chillies

1/2 pound mustard seed

2 ounces minced garlic

1/2 pound dried peas

1/2 pint vinegar

1/4 pound saffron

1/4 pound pepper

2 ounces dry ginger

1/2 pound salt

1/4 pound brown sugar

2 ounces cumin seed

1/2 pint lucca oil

N.D.—Few Bay Leaves in Ceylon and India. Using Curry Leaves, black.

Mode.—Grind all the above with the vinegar using to moisten the ingredients, using a Curry stone or stone-made pounder. When all the above nice and thin as a paste, put in a jar and pour over the Lucca oil, and cover it up. Use a large spoon for Madras Curries. The above good for mushroom, snipe, partridge, and other brown Curries of superior quality.

Source: The Curry Cook’s Assistant; or Curries, How to Make Them in England in Their Original Style, by Daniel Santiagoe. London: J. Kegan Paul, Trench, & Co., 1889.