Story and Photos by Sharon Hudgins

Actually they’re already here. Mongol cuisine—or dishes dubbed “Mongolian”—has taken the world by storm, like a horde of horse-mounted warriors galloping out of Central Asia on a global raiding party.

Mongolian barbecue. Mongolian hot pot. Jingisukan (I’ll bet you can figure that one out). From hole-in-the-wall mom-and-pop joints to look-alike chain restaurants to elegant eateries atop modern highrises around the world, you’ll find food that calls itself Mongolian. But none of it really is.

Let’s start with Mongolian food on its home soil. Meat and milk have been the mainstays of Mongolian nomads’ cuisine for thousands of years. Mongol herders consume the flesh and dairy products from all the animals they raise: sheep, goats, horses, cattle (including yaks and hybrid hainags), Bactrian camels, and, in some places, reindeer. Vegetables were never part of a nomad’s diet. “Meat is for men, grass is for animals,” they say. But contact with the Chinese, and later the Russians, eventually brought a few vegetables into the Mongolian kitchen—potatoes, cabbages, carrots, onions, beets, turnips, bell peppers—along with grains such as wheat, barley, and rice. Sometimes this basically bland fare is even perked up a bit with black pepper or a dash of hot red pepper.

Although the landscape of Mongolia looks a lot like Wyoming and Montana, the food that Mongolians call “barbecue” is very different from the meat a western cowboy would expect to find on his tin plate. And so-called “Mongolian barbecue” outside of Mongolia itself has nothing to do with the way Mongolians actually barbecue their meat.

Real Mongolian Barbecue

If a Mongolian invites you to a barbecue, don’t expect to be served the slow-smoked, falling-off-the-bones beef of Texas or pulled pork of the Deep South. Nor the quick-cooked, grill-seared meats called “barbecue” from Australia to California to Europe.

In Mongolia, barbecue means meat cooked just like they did in the Stone Age, literally. Today almost all Mongolian meats are simply boiled in water in a big open pot. But the two exceptions are the Mongolians’ traditional barbecue: horhog (which has nothing to do with the porcine species) and boodog (which sounds like a canine from Louisiana, but isn’t). Both kinds of Mongolian barbecue are made outdoors, not inside the nomads’ gers (yurts). They’re summertime foods, usually cooked for annual celebrations and other special occasions, like the arrival of guests from afar.

Horhog is made in a large, tightly covered, cylindrical metal pot, often a repurposed 10-gallon milk can. A typical recipe calls for “One-half sheep or goat, potatoes (optional), carrots (optional), onions (optional), turnips (optional), cabbage (optional), bell pepper (optional), garlic (optional), black pepper (optional), salt, and water.” You get the drift.

Horhog is made in a large, tightly covered, cylindrical metal pot, often a repurposed 10-gallon milk can. A typical recipe calls for “One-half sheep or goat, potatoes (optional), carrots (optional), onions (optional), turnips (optional), cabbage (optional), bell pepper (optional), garlic (optional), black pepper (optional), salt, and water.” You get the drift.

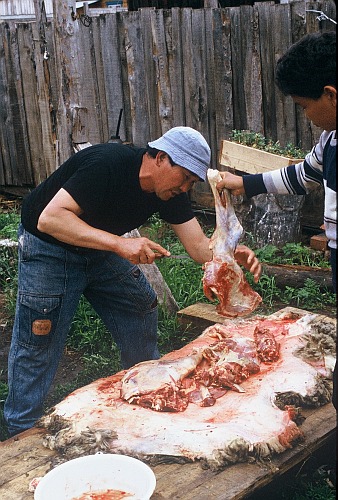

First the sheep and optional vegetables are cut into large chunks, including most of the organ meats. Then smooth, round, fist-size river stones are heated in an open fire made from dried animal dung. The red-hot stones, raw meat, bones, vegetables, and spices are layered in the pot, water is poured inside, the pot is quickly covered, and the lid is weighted down with stones to seal in the steam. Some people just let the hot stones inside the pot slow-cook the ingredients. Others set the pot on a ring of stones encircling the fire, so the ingredients will steam-boil more quickly with the addition of external heat. The process takes about one and a half hours, with the lid tightly closed the whole time. Only the aroma and sounds escaping from the pot tell the cook when the horhog is ready to eat.

The hot, greasy stones are carefully removed from the pot, then the meat and vegetables are pulled out and set aside on platters. As soon as the stones are no longer too hot to handle, they’re passed around among the diners to warm their hands and, supposedly, to reduce fatigue and boost stamina. Finally it’s time to eat: first the meat and vegetables (usually eaten with your fingers), then the rich, hot broth from the pot, ladled into individual bowls for drinking.

The preparation of boodog is more dramatic. As a Mongolian culinary website notes, “…boodog is a group meal, which is very popular in camping and outdoor activities…Boodog cooking also involves a lot of fun and friendship; however, it requires far more artistry and practice than horhog cooking.” You bet it does.

A freshly slaughtered borlon (2-year-old goat) or a marmot shot during game season is decapitated, then eviscerated (and sometimes de-boned) through the neck opening, without cutting open the skin anywhere else. Sometimes the interior is salted and the liver and kidneys returned to the carcass cavity. Smooth round river stones are heated over an open fire and then carefully inserted into the carcass before the neck opening is tied shut. The hair on the outside is seared off by holding this stone-filled skin “bag” over the open flames, but modern Mongolians are just as likely to use a blowtorch. Both heat sources—the stones inside and the flame outside—cook the meat simultaneously, from opposite directions. As the Mongolian website cautions, “This process must be handled with care and expertise. The temperature of stones and the amount of heat from outside must be well balanced and regulated. Otherwise, a lot of pressurized vapor will accumulate inside the meat and the whole package may blow up.”

If your barbecued goat or marmot hasn’t exploded into tiny bits of meaty shrapnel, then start your meal by passing around and fondling those health-giving hot rocks, then use your hunting knife to dig into the cooked meat. Enjoy!