Story and Photos by Sharon Hudgins

Humble horseradish has become a hot seasoning among trendy cooks in America. But in the Old World it’s old hat—an ingredient that’s traditionally been used to spike up bland dishes long before Columbus brought the first chile pepper seeds back to Europe.

Horseradish, both wild and cultivated, grows in many parts of the world. Today it’s most often associated with the cuisines of Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, Scandinavia, and Britain. But horseradish as a food can trace its roots back at least 3,000 years, when some adventurous eater first bit off a piece of the pungent root and was knocked backward by the blow to his head. Eventually the hunger for heat just increased the demand for it. A Greek legend, no doubt concocted by an ancient vegetable merchant, recounts the Oracle of Delphi saying to Apollo, “The radish is worth its weight in lead, the beet its weight in silver, and the horseradish its weight in gold.”

Centuries ago, Jews began eating horseradish at their Passover seders as one of the five “bitter herbs” symbolizing the bitterness of their long-ago bondage in Egypt. By the Middle Ages horseradish was being cultivated for both culinary and medicinal purposes in Europe. The root and leaves were eaten as a vegetable, and the root was also used as a bittering agent, like hops, in beer. Today, Germans still make horseradish schnapps, and some even add a pinch of horseradish to their beer. And in Austria, vendors at sausage stands grate fresh horseradish on the spot as a piquant accompaniment to their juicy links.

Horseradish eventually spread from Central and Eastern Europe to Scandinavia and England. According to food historian Waverly Root, the first recorded mention of its use in England was in 1640, where it was considered a crude food, eaten by “country people and strong laboring men…[but] too strong for tender and gentle stomachs.” By the 18th century, however, horseradish had become such an accepted accompaniment to roast beef that English silversmiths produced special ornate horseradish pots and spoons, for serving the condiment properly at the table.

Not everyone was so enthusiastic about it, though. In the 19th century, the Alexandre Dumas warned his readers that “Horseradish has the same disadvantages of the true French turnip. It is equally apt to bring on flatulence, causes a heaving of the stomach, and even produces headaches when too much of it is eaten.”

Hungarian George Lang recounts that in one region of his country, “Old timers will tell you that everyone…always ate three bites of horseradish before Easter luncheon so that if in the following year he slept outside with his mouth open, he would not have a snake crawl into it.” If that horseradish didn’t deter the snake, then very likely the pungent root would have been used to treat the bite. Horseradish was valued in medieval Europe as a medicinal plant, used for treating all kinds of ailments from infected cuts and intestinal worms to arthritis and chest congestion. Healthy horseradish is low in calories and sodium, high in vitamin C, and a good source of calcium, iron, and potassium—if you can manage to eat enough of it.

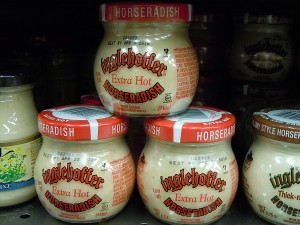

Extra-hot bottled horseradish contains fewer other ingredients than most bottled horseradish products.

Horseradish was brought to North America by early settlers from Europe who began cultivating it in the East Coast colonies. And in the United States today, millions of pounds of horseradish roots are processed commercially for making bottled products sold in grocery stores: basic prepared horseradish (usually mixed with salt and vinegar), milder cream-style horseradish, ruby-red beet horseradish, cocktail sauce for seafood, horseradish mayonnaise, and a variety of hot mustards, from tangy to incendiary.

Although both the root and the leafy green leaves are edible, horseradish is cultivated primarily for its roots. To be honest, they’re not a pretty sight: 8 to 12 inches long, gnarled and knobby, with a rough light-brown skin and a tough, ivory-colored, fibrous interior. Food writer Elizabeth Schneider aptly described them as looking “like something that may have belonged to a male mastodon and was fossilized for eons before arriving in the vegetable market.”

The most pungent of edible roots, horseradish has hardly any aroma until the roots are broken. Cutting, grating, or grinding releases the volatile oils, natural chemical substances that immediately go to your head, searing your sinuses and bringing tears to your eyes. It also packs a punch to your taste buds. But grated horseradish gradually loses its distinctive potency. And when it’s used in cooking, the heat drives off the volatile oil and diminishes the bite of the root. So if you want horseradish to retain its hotness and flavor, add it toward the end of the cooking process—or use it in cold condiments such as horseradish-spike mayo and sour cream.

Freshly grated horseradish is stronger in flavor and heat than the commercially bottled product. So if you like the taste and don’t mind the tears, process your own horseradish at home. Buy a fresh, firm, whole horseradish root, available at many larger grocery stores. (If you aren’t going to use it right away, wrap it loosely in a paper towel and a plastic bag, and keep it stored in the refrigerator.) Scrub off the dirt and peel the root with a vegetable peeler, then grate it by hand with a Microplane grater, or shred it in a food processor fitted with the standard cutting blade. Work in a well ventilated place, and don’t wear eye makeup! Mix the grated horseradish with a little vinegar and salt (some people like to add a bit of sugar, too), and store it in a jar in the refrigerator. Once you’ve tasted freshly prepared horseradish, you’ll understand why it’s truly a radish to root for.

Hot Tips

● To make really devilled eggs, add grated horseradish to the egg yolk mixture.

● Combine 2 tablespoons grated horseradish with a large apple, grated, to serve as a condiment with poached fish.

● Mix 1/4 cup grated horseradish and 2 teaspoons lemon juice with 1 cup mayonnaise to use as a sandwich spread.

● Combine 1 cup applesauce, 1/4 cup grated horseradish, and 1 teaspoon Hungarian paprika to use as an accompaniment to roasted turkey, goose, duck, or pork.

● Mix 1/4 cup grated horseradish and 1 teaspoon lemon juice with 1 cup sour cream to use as a garnish for grilled or smoked meats and fish, and also as a filling for baked potatoes, sprinkled with chopped chives.

● Spike up creamed vegetables by adding 1/2 cup grated horseradish to 2 cups of the béchamel sauce before combining it with the vegetables.

● Whip 1/2 cup of heavy cream until stiff, then fold in 1/4 cup horseradish and use as a garnish for cold ham or roast beef.

● Mix 2 tablespoons grated horseradish with 1 cup mild mustard to spread on hamburger buns or on sliced bread for ham or roast beef sandwiches.

● Add 2 to 4 tablespoons grated horseradish and 2 teaspoons lemon juice to 1 cup whole-berry cranberry sauce and use as a garnish for turkey or pork.

● Mix horseradish with apricot preserves and mustard as a glaze for baked ham.

● Mash together 8 ounces of cream cheese (at room temperature), 1/2 cup grated horseradish (drained of any liquid), 1/4 cup finely chopped fresh chives or green onion tops, and 1 to 2 tablespoons of buttermilk as a spread for rye or pumpernickel bread, bagels, and crackers.