By Dave DeWitt

Above, the Sierra Madre, Home of Chiltepins

My amigo Antonio swears that the motto of the Sonoran bus lines is “Better Dead Than Late,” and I believe him. The smoke-belching buses were flying by us on curves marked by shrines commemorating the unfortunate drivers whose journeys through life had abruptly ended on this mountain road. We waved the buses on and cruised along at a safer speed to enjoy the spectacular vistas on the way to the valley of the chiltepíneros.

It was November, 1990, the time of the Sonoran chiltepin harvest, yet the temperature was in the upper 80s. My wife, Mary Jane, and I had accepted the invitation of Antonio Heras to visit the home of his mother, Josefina, the “chile queen,” who lives in the town of Cumpas. From there, we journeyed through the spectacular scenery of the foothills of the Sierra Madre range–chiltepín country. Our destination was the Rio Sonora valley and the villages of La Aurora and Mazocahui.

As we drove along, Antonio and I reminisced about our fascination with the wild chile pepper.

A Fiery Flashback

During the early days of the Chile Pepper magazine, both of us had attended a symposium on wild chiles that was held in October, 1988, at the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix. The leader of the conference was the ecologist Dr. Gary Nabhan, author of Gathering the Desert, director of Native Seeds/SEARCH, and an expert on chiltepíns. Other chile experts attending included Dr. W. Hardy Eshbaugh, a botanist from Miami University of Ohio; Dr. Jean Andrews, author of Peppers: The Domesticated Capsicums; and Cindy Baker of the Chicago Botanical Garden.

As the conference progressed, I was amazed by the amount of information presented on chiltepíns. Botanists believe that these wild chiles are the closest surviving species to the earliest forms of chiles which developed in Bolivia and southern Brazil long before mankind arrived in the New World. The small size of their fruits were perfect for dissemination by birds, and the wild chiles spread all over South and Central America and up to what is now the United States border millennia before the domesticated varieties arrived. In fact, Dr. Eshbaugh believes they have the widest distribution of any chile variety; they range from Peru north to the Caribbean, Florida, and Louisiana and west to Arizona.

There is a wide variation in pod shapes, from tiny ones the size and shape of BBs to elongated pods a half inch long. By contrast, domesticated piquins have much longer pods, up to three inches. The chiltepíns most prized in Mexico are spherical and measure five to eight millimeters in diameter. They are among the hottest chiles on earth, measuring up to 100,000 Scoville Heat Units.

The word “chiltepín” is believed to be derived from the Aztec language (Nahuatl) combination word “chilli” + “tecpintl,” meaning “flea chile,” an allusion its sharp bite. That word was altered to “chiltecpin,” then to the Spanish “chiltepín,” and finally Anglicized to “chilipiquin,” as the plant is known in Texas. We have settled on a non-accented “chiltepín” as the English term for the plant and fruit. Its botanical name is Capsicum annuum var. gabrisculum.

In Sonora and southern Arizona, chiltepíns grow in microhabitats in the transition zone between mountain and desert, which receives as little as ten inches of rain per year. They grow beneath “nurse” trees such as mesquite, oak, and palmetto, which provide shelter from direct sunlight, heat, and frost. In the summer, there is higher humidity beneath the nurse trees, and legumes such as mesquite fix nitrogen in the soil–a perfect fertilizer for the chiltepíns. They also protect the plant from grazing by cattle, sheep, goats, and deer. chiltepíns planted in the open, without nurse trees, usually die from the effects of direct solar radiation.

Although the chiltepín plant’s average height is about four feet, there are reports of individual bushes growing ten feet tall, living twenty-five to thirty years, and having stems as big around as a man’s wrist. chiltepíns are resistant to frost but lose their leaves in cold winter weather. New growth will sprout from the base of the plant if it is frozen back.

There is quite a bit of legend and lore associated with the fiery little pods. In earlier times, the Papago Indians of Arizona traditionally made annual pilgrimages into the Sierra Madre range of Mexico to gather chiltepíns. Dr. Nabhan discovered that the Tarahumara Indians of Chihuahua value the chiltepíns so much that they build stone walls around the bushes to protect them from goats. Besides spicing up food, Indians use chiltepíns for antilactation, the technique where nursing mothers put chiltepín powder on their nipples to wean babies. chiltepíns are also an aid in childbirth because when powdered and inhaled they cause sneezing. And, of course, the hot chiles induce gustatory sweating, which cools off the body during hot weather.

In 1794, Padre Ignaz Pfeffercorn, a German Jesuit living in Sonora, described the wild chile pepper: “A kind of wild pepper which the inhabitants call chiltipin is found on many hills. It is placed unpulverized on the table in a salt cellar and each fancier takes as much of it as he believes he can eat. He pulverizes it with his fingers and mixes it with his food. The chiltipin is the best spice for soup, boiled peas, lentils, beans and the like. The Americans swear that it is exceedingly healthful and very good as an aid to the digestion.” In fact, even today, chiltepíns are used–amazingly enough–as a treatment for acid indigestion.

Padre Pfeffercorn realized that chiltepíns are one of the few crops in the world that are harvested in the wild rather than cultivated. (Others are piñon nuts, Brazil nuts, and some wild rice.) This fact has led to concern for the preservation of the chiltepín bushes because the harvesters often pull up entire plants or break off branches. Dr. Nabhan believes that the chiltepín population is diminishing because of overharvesting and overgrazing. In Arizona, plans are underway to establish a chiltepín reserve near Tumacacori at Rock Corral Canyon in the Coronado National Forest. Native Seeds/SEARCH has been granted a special use permit from the National Forest Service to initiate permanent marking and mapping of plants, ecological studies, and a management plan proposal.

The symposium on wild chiles was fascinating, and we even got to taste some chiltepín ice cream. But, it was even more interesting to see the chiltepíneros in action two years later.

In the Village of the Dawn

The only way to drive to the village of the dawn (La Aurora) is to ford the Rio Sonora, which was no problem for Antonio’s Jeep. The first thing we noticed about the village was that nearly every house had thousands of brilliant red chiltepíns drying on white linen cloths in their front yards. We stopped at the modest house of veteran chilepinero Pedro Osuna and were immediately greeted warmly and offered liquid refreshment. As Pedro measured out the chiltepíns he had collected for Antonio and Josefina, we asked him about the methods of the chiltepíneros.

He said that the Durans advanced him money so he could hire pickers and pay for expenses such as gasoline. Then he would drive the pickers to ranches where the bushes were numerous. He dropped the pickers off alongside the road, and they wandered through the rough cattle country handpicking the tiny pods. In a single day, a good picker could collect only six quarts of chiltepíns. At sunset, the pickers returned to the road, where Pedro met them. The ranchers who owned the land would later be compensated with a liter or so of pods.

Usually, the pods would be dried in the sun for about ten days. But because that technique is lengthy and often results in the pods to collecting dust, Antonio had built a solar dryer in back of Pedro’s house. Air heated by a solar collector rose up a chimney through racks, with screens holding the fresh chiltepíns–a much more efficient method. Modern technology, based upon ancient, solar-passive principles, had arrived at the village of the dawn.

Pedro Osuna Measures Out the Tiny Pods

Pedro Osuna Measures Out the Tiny Pods

I asked Pedro how the harvest was going, and he said it was the best in more than a decade because the better than average rainfall had caused the bushes to set a great many fruits. Antonio added that during the drought of 1988, chiltepíns were so rare that there was no export crop. According to Pedro, factors other than rainfall also had an influence on the harvest–specifically, birds and insects. Mockingbirds, pyrrhuloxia (Mexican cardinals), and other species readily ate the pods as they turned red, but the real damage to the entire plant was caused by grasshoppers.

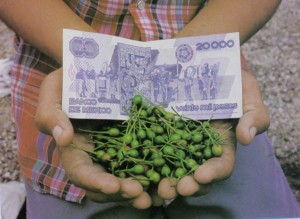

The total harvest in Sonora is difficult to estimate, but at least twenty tons of dried pods are collected and sold in an average year. Some chiltepíneros have suggested that in a wet year like 1990, fifty tons might be a better estimate. The total export to the United States is estimated at more than six tons a year, and the Durans account for much of that. As I watched Antonio and his mother weigh huge sacks of chiltepíns on the small scale in front of the market, I asked Antonio about prices.

He declined to tell me what he paid the chiltepíneros, but he offered a wealth of information about other pricing information. Between 1968 and 1990, the wholesale price of chiltepíns had multiplied nearly ten fold. Between 1987 and 1990, the price had nearly tripled, mostly because of the 1988 drought. Currently, chiltepíns were being sold in South Tucson in one-quarter ounce packages for $2.00, which equates to a phenomenal $128 per pound. Thus, chiltepíns are the second most expensive spice in the world, after saffron.

Why do people in the United States lust after these tiny pods? Dr. Nabhan suggests that chiltepíns remind immigrants of their northern Mexico homeland and help them reinforce their Sonoran identity. Also, they have traditional uses in Sonoran cusine, as evidenced by the recipes we collected. In addition to spicing up Sonoran foods, they are an anti-oxidant and thus help preserve carne seca, the dried meat we call jerky. No wonder the Chile Queen and her son work hard to import many hundreds of pounds of pods.

After the sacks of chiltepíns were loaded into the Jeep, we were joined by Arizona Republic reporter Keith Rosenblum, who was writing a story on the chiltepíneros. We went for lunch in the nearby village of Mazocahui, passing signs reading “Se Vende chiltepín,” chiltepíns for sale. At the rustic restaurant, which was really the living room of someone’s house, we sat down for a fiery feast. Bowls of chiltepíns were on the table, and the extremely hot salsa casera was served with carne adovada, carne machaca, beans, and the superb, extremely thin Sonoran flour tortillas.

The Future of Chiltepíns

On the drive back to Cumpas, Antonio spoke of his dreams–and the problems inherent in achieving them. He wanted to create a chiltepín plantation, where all the bushes were centrally located and irrigated, thus eliminating wasted time and money with pickers wandering for miles through rough country.

I reminded him of the problems with previously cultivated chiltepín crops that we had learned about at the symposium. In those experiments, growers had planted the chiltepíns in rows under artificial shade and had irrigated them as if they were growing Jalapeños. The cultivated chiltepíns had the tendency to produce pods fifty percent larger than the wild variety, which did not seem authentic and thus were rejected by consumers. Several reasons for the occurrence of the larger pods had been advanced. There was the natural tendency of growers to select larger pods for their seed stock for the following year, which is how chiles developed from BB sized to the large pods we have today. Also, increased water and fertilizer could enlarge the pods.

The wild plants, when cultivated, were susceptible to chile wilt, the fungal disease aggravated by too much water. In one test planting near the Rio Montezuma, the chiltepín plants were wiped out by moth caterpillars, yet a wild population just two miles away was unaffected. One possible explanation had been offered: during times of drought, chiltepíns went dormant, as did their nurse plants. However, during the drought, chiles that were cultivated in rows and irrigated stuck out like sore thumbs and attracted pests.

But Antonio had a plan to eliminate those problems. He would mimic nature, he told me, and improve on it only slightly. He envisioned a “natural plantation,” one near Cumpas where he would plant thousands of chiltepín plants under mesquite nurse trees and provide drip irrigation to them. There were plenty of friends and relatives–especially kids–to scare off birds, to spread netting to defeat grasshoppers, and to pick the crop. Dogs would guard the crop from unauthorized harvesters, and Antonio’s solar dryers would provide a clean, perfect crop. It seemed eminently logical to me, and I wished him luck.

Back in the town of Cumpas, loud salsa music enlivened the streets as if a fiesta were in progress. Josefina and her assistant Evalia prepared a wonderful, chiltepín-spiced meal. We drank some bacanora, the magical Mexican moonshine, and dined on an elegant–and highly spiced–menu of Sonoran specialties.

I felt inspired. After submerging myself in the chiltepín culture of Sonora, I was very comfortable in saying, “Yo soy un chiltepínero,” I am a chiltepínero.

[Author’s Note: Antonio never achieved his chiltepín dreams–the project had way too many variables. We still are in contact with each other, and now he sells U.S heavy machinery to companies in Mexico. I checked on chiltepín prices online in 2008 and found eight ounces for $42.95, or $85.90 per pound, so the price goes down if you buy in “bulk.”]

Salsa Casera

(Chiltepín House Sauce)

This diabolically hot sauce (at least a 9 on the heat scale) is also called chiltepín pasta (paste). It is used in soups and stews and to fire up machaca, eggs, tacos, tostadas, and beans. This is the exact recipe prepared in the home of Josefina Duran in Cumpas, Sonora. After I returned to Albuquerque, I made this sauce and it sat in my refrigerator for years, and because it was so hot, I never came close to finishing the jar of it.

2 cups chiltepíns

8 to 10 cloves garlic

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon Mexican oregano

1 teaspoon coriander seed

1 cup water

1 cup cider vinegar

Combine all ingredients in a blender and puree on high speed for 3 to 4 minutes. Refrigerate for one day to blend the flavors. It keeps indefinitely in the refrigerator.

Yield: 2 cups

Heat Scale: Extremely hot

Chiltepínes en Escabeche

Photo: Mitch McClaran

Photo: Mitch McClaran

In the states of Sonora and Sinaloa, fresh green and red chiltepíns are preserved in vinegar and salt. They are used as a condiment or are popped into the mouth when eating any food–except, perhaps, oatmeal. Since fresh chiltepíns are not available in the U.S., adventurous cooks and gardeners must grow their own. The tiny chiles are preserved in three layers in a 1 pint, sterilized jar.

Fresh red and/or green chiltepíns (as many as you want to pickle)

3 cloves garlic, peeled

3 teaspoons salt

3 Tablespoons cider vinegar

Water

Fill the jar one-third full of chiltepíns. Add 1 clove garlic, 1 teaspoon salt, and one tablespoon cider vinegar. Repeat this process twice more and fill the jar to within 1/2 inch of the top with water.

Seal the jar and allow to sit for 15 to 30 days.

Yield: 1 pint

Heat Scale: Hot

Agua Chile

(“Chile Water”)

One of the most basic chiltepín dishes known, this recipe is prepared only in the state of Sinaloa, where the chiltepíns produce fruits all year long. This simple soup is served in mountain villages, and everyone makes his own in a soup bowl.

2 chiltepíns (or more, to taste), crushed

1 garlic clove, chopped

1/4 ripe tomato, diced

Pinch Mexican oregano

Pinch salt

Boiling water

In a soup bowl, add all ingredients except the water and mix together. Add boiling water to the desired consistency and mash everything together with a large spoon.

Yield: 1 serving

Heat Scale: Medium

Capón de Ajo

(Chopped Garlic Soup with chiltepíns)

Another basic chiltepín soup. This one is for true garlic lovers!

4 chiltepíns (or more, to taste), crushed

8 to 10 cloves garlic, chopped

1/2 onion, chopped (optional)

1 tablespoon vegetable oil or butter

2 cups boiling water

1 thin flour tortilla, heated on a griddle until crisp

Saute the garlic and onions in the oil or butter until soft, then transfer to a soup bowl. Add the chiltepíns and pour in the boiling water. Break the tortilla into pieces and add it to the liquid.

Yield: 1 serving

Heat Scale: Hot

Carne Adovada Estilo Sonora

(Sonoran-Style Marinated Pork)

This unusual recipe is half jerky and half grilled pork. Don’t worry about exposing the meat to the air; the vinegar is the high-acid preservative.

10 dried red New Mexican chiles, stems removed, seeds removed and saved

10 chiltepíns (or more to taste), seeds removed and saved

4 pounds pork tenderloin, sliced into strips 1/4 to 1/2 inch thin*

3 large cloves garlic

1 teaspoon Mexican oregan

1 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup cider vinegar

1/2 cup water

Corn or flour tortillas

1 small cabbage, chopped

Juice of 4 limes

*For easier slicing, freeze the pork slightly, then slice

Boil the New Mexican chiles until they are soft. Add all the other ingredients except the pork, chile seeds, and tortillas and puree in a blender to make the marinade.

Add the seeds to the chile marinade and marinate the pork in the mixture for an 1 hour. Hang the strips of meat over a clothesline in the sun and arrange cheesecloth around them to keep the insects away. Dry the meat in the sun for two days in dry weather and then refrigerate until ready to use.

Grill the meat strips over mesquite wood for 1 to 2 minutes per side. Dice the strips and spread the meat over thin flour or corn tortillas. Spread chopped cabbage over the meat and sprinkle lime juice over the top. Fold the tortilla in half and serve.

Yield: 8 servings

Heat Scale: Hot to extremely hot

Caldo Puchero

(Pot of Vegetable Stew with Chiltepíns)

Like most stews, this one takes a while to cook, about 4 hours. It is interesting because it contains a number of pre-Columbian ingredients, namely chiltepíns, corn, squash, potatoes, and tepary beans. The heat level can be adjusted by adding or subtracting chiltepíns.

15 chiltepíns, or more to taste

3 green New Mexican chiles, roasted, peeled, seeds and stems removed, chopped

1 beef soup bone with marrow

1 cup dried tepary or garbanzo beans

4 cloves garlic, chopped

1 acorn or butternut squash, peeled, seeds removed, and cut into 1-inch cubes

3 ears corn, cut into 2-inch rounds

4 carrots, cut into 1-inch pieces

1 head cabbage, quartered

3 stalks celery, cut into 1-inch pieces

2 large potatoes or sweet potatoes, cut into 1-inch cubes

3 zucchini squash, peeled and cut into 1/2-inch slices

1 onion, quartered

2 cups fresh string beans, cut into 1-inch pieces

1/2 cup minced fresh cilantro

Water

In a large soup kettle combine the chiltepíns, soup bone, beans, garlic, and twice as much water as needed to cover. Bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer for 1 hour.

Add the acorn or butternut squash, the corn, and more water and simmer for 30 minutes.

Add the carrots and cabbage and simmer for 15 minutes.

Add the green chiles, celery, and potatoes and cook for 30 minutes.

Add the zucchini, onion, and string beans and simmer for 30 to 45 minutes until everything is tender.

When ready to serve, remove the kettle from the heat, remove the soup bone, and add the cilantro.

Yield: 8 servings

Heat Scale: Hot

Sonoran Enchiladas

Make thick corn tortillas like this one.

Make thick corn tortillas like this one.

These enchiladas are not the same as those served north of the border. The main differences are the use of freshly made, thick corn tortillas and the fact that the enchiladas are not baked. We dined on these enchiladas one night in Tucson as they were prepared by Cindy Castillo, a friend of the Duran family, who is well-versed in Sonoran cookery.

The Sauce:

15 to 20 chiltepíns, crushed

15 dried red New Mexican chiles, seeds and stems removed

3 cloves garlic

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon vegetable oil

1 teaspoon flour

In a saucepan, combine the chiles, salt, and enough water to cover. Boil for ten or fifteen minutes or until the chiles are quite soft.

Allow the chiles to cool and then puree them in a blender along with the garlic. Strain the mixture, mash the pulp through the strainer, and discard the skins.

Heat the oil in a saucepan, add the flour, and brown, taking care that it does not burn. Add the chile puree and boil for five or ten minutes until the sauce has thickened slightly. Set aside and keep warm.

The Tortillas:

2 cups masa harina

1 egg

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 teaspoon salt

Water

Vegetable oil for deep frying

Mix the first four ingredients together thoroughly, adding enough water to make dough. Using a tortilla press, make the tortillas. Deep fry each tortilla until it puffs up and turns slightly brown. Remove and drain on paper towels and keep warm.

To Assemble and Serve:

3 to 4 scallions, minced (white part only)

2 cups grated queso blanco or Monterey Jack cheese

Shredded lettuce

Place a tortilla on each plate and spoon a generous amount of sauce over it. Top with the cheese, lettuce, and onions.

Yield: 4 to 6 servings

Heat Scale: Hot

Chiltepín Chorizo

There are as many versions of chorizo in Mexico and the Southwest as there are of enchiladas. Essentially, it is a hot and spicy sausage that is served with eggs for breakfast, as a filling for tostados or tacos, or mixed with refried beans. This Sonoran version is spicier than most, and, in addition, it is served crumbled rather than being formed into patties.

15 to 20 chiltepíns, crushed

1 cup red New Mexican chile powder

1 tablespoon chile seeds (from chiltepíns or other chiles)

1 pound ground lean pork

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1/2 teaspoon Mexican oregano

3 tablespoons white vinegar

4 cloves garlic, minced

1/2 teaspoon ground cloves

Combine the pork with the rest of the ingredients, mix well, and let it sit at room temperature for one or two hours, or in the refrigerator overnight. (It keeps well in the refigerator for up to a week. Or, freeze the chorizo in small portions and use as needed.)

Fry the chorizo until it is well-browned.

Yield: 4 servings

Heat Scale: Hot to Extremely Hot

Machaca Sierra Madre

Machaca Burrito

Machaca Burrito

The word “machaca” derives from the verb machacar, to pound or crush, and that description of this meat dish is apt. The shredded meat is often used as a filling for burritos or chimichangas and is sometimes dried. Serve the meat wrapped in a flour tortilla along with shredded lettuce, chopped tomatoes, grated cheese, and sour cream, which will reduce the heat level a bit.

3 pound arm roast

Water

10 to 15 chiltepíns, crushed

1 and 1/2 cups chopped green New Mexican chile which has been roasted, peeled, and had stems removed

1 cup peeled and chopped tomatoes

1/2 cup chopped onions

2 cloves garlic, minced

Put the roast in a large pan and cover with water. Bring to a boil, reduce heat, cover, and simmer until tender and until the meat starts to fall apart, about 3 or 4 hours. Check it periodically to make sure it doesn’t burn, adding more water if necessary.

Remove the roast from the pan and remove the fat. Remove the broth from the pan, chill, and remove the fat. Shred the roast with a fork.

Return the shredded meat and then the defatted broth to the pan, add the remaining ingredients, and simmer until the meat has absorbed all the broth.

Yield: 6 to 8 servings

Heat Scale: Hot

Chiltepín Ice Cream

This novelty was first served in 1988 for the symposium on wild chiles at the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix and at the Fiesta de los Chiles at the Tucson Botanical Gardens. It is very hot in the proportions given (despite the tendency of ice cream to cut the heat), so you may want to reduce the quantity of chiltepíns.

1/2 cup Chiltepínes en Escabeche (see recipe), rinsed thoroughly and pulverized (or substitute fresh green or red pods)

1 gallon vanilla ice cream

Combine all ingredients and mix thoroughly in a blender until green flecks appear throughout the ice cream. Serve in small portions.

Yield: 20 servings

Heat Scale: Hot