by Dave DeWitt

Recipes:Indonesian Chile Paste Curry Puffs Curried Coconut Beef White Chicken Curry Prawn Curry Singapore Fish Head |

Borneo Women Collecting Fruits for Curries

The original Spice Islands were the Moluccas, those remote isles of cloves and nutmeg that lie 1,500 miles east of Djakarta, Indonesia. But throughout history, the location of the Spice Islands gradually broadened to include all of the East Indies–now the countries of Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore. There was a simple reason for the broader definition: the spice-growing locations expanded as the region was conquered-or plundered–by one spice-seeking world power after another: The Arabs, Romans, Indians, Portuguese, Dutch, and finally the Americans.

Today, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia are separate, independent countries, and these “spice islands” still live up to their name. Indonesia produces about seventy percent of the world’s nutmeg and mace, plus large amounts of cassia, turmeric, black pepper, and cloves. Most of the cloves, incidentally, are not eaten but rather are smoked in cigarettes. Other curry ingredients grown in the region include chiles, ginger, galangal, fruits, lemongrass, kaffir lime, and coconuts–perhaps the most important single ingredient in Spice Islands curries. These culinary components, combined with the many ethnic influences on the region, have produced a fascinating and complex gastronomic stew.

A Melding of Cultures and Cuisines

In addition to the original Malays and all the other peoples who have inhabited the Spice Islands, one other group also emigrated there–the Chinese. Although the region was visited by traders from China for centuries, the first main Chinese influx came in 1820s, as immigrants worked as construction workers on the building of Singapore, and the second wave of laborers came in the 1840s to work the tin mines.

The influence of the Chinese, who now comprise about three-quarters of the population of Singapore, has been vast. The major Chinese immigrants were Hokkiens (from Fujian province), Teochews, Cantonese, and Hainanese. All brought their own regional cultures and food traditions to the region and settled in their own enclaves in Singapore and Malaysia. Most of earliest Chinese settlers were men, and because of the lack of Chinese women, they married Malay women. Thus a distinct subculture was born, known in Malay as peranakan (meaning “to be born here”), and in English as “Straits Chinese.” The women of that subculture were known as nonyas, Malay for “ladies.”

The intermarriage of Chinese men and Malay women ended once the population of Singapore grew large enough to include Chinese women, and Nonyas eventually became part of the mainstream of Singapore culture. Their influence lives on in Nonya cooking, a blend of Chinese subtlety and techniques and spicy Malay ingredients. It has been said that in one meal, the diner receives a perfect balance of opposing flavors, textures, and colors.

The British, of course, also had an influence on the culture of the region. After Sir Stamford Raffles colonized Singapore for the British, the small fishing village became the leading port east of the Suez Canal. The British influence accounts for the fact that the principal language of Singapore is English (other official languages are Tamil, Malay, and Cantonese), but the British had a much lesser impact on the food. Nowadays, about the only surviving British culinary heritage involves drinking; the hotels and restaurants serve high tea in the afternoon, excellent Singapore-brewed beers and stouts, and plenty of gin drinks.

The British, of course, also had an influence on the culture of the region. After Sir Stamford Raffles colonized Singapore for the British, the small fishing village became the leading port east of the Suez Canal. The British influence accounts for the fact that the principal language of Singapore is English (other official languages are Tamil, Malay, and Cantonese), but the British had a much lesser impact on the food. Nowadays, about the only surviving British culinary heritage involves drinking; the hotels and restaurants serve high tea in the afternoon, excellent Singapore-brewed beers and stouts, and plenty of gin drinks.

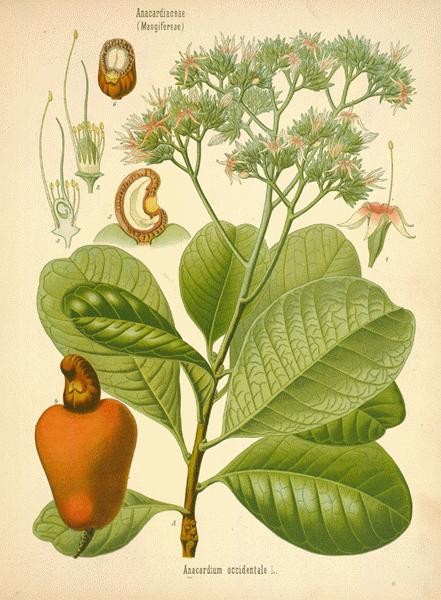

Cashew Botanical Print

The expansion of Singapore as a major trading center led to settlement by other ethnic groups. The main Indian immigration came during the nineteenth century, when indentured Indian laborers came to work on the rubber plantations, and now the population of Singapore is about six and a half percent Indian. Under British control, the settlers were kept in their own ethnic enclaves, so they could not easily unite and rebel. These enclaves–such as Chinatown, Arab Street, and Little India–though unofficial now, still exist to this day, and each area has its own markets, spice shops, and restaurants.

Beyond a doubt, the two principal foods of the region are rice and seafood. Rice was introduced by Indian traders about A.D. 1000, and dozens of varieties are grown and consumed in the region. Because of the proximity to the sea, the Spice Islands have a great variety and abundance of seafood. Three very popular items are red snapper, prawns, and clams.

The most popular cooking style of the Spice Islands is currying. “Curries, easily the most common dish eaten with rice, are a definite mark of the Indian influence in Malay cooking,” notes Singapore restaurateur Fawziah Amin. “For almost every meal, a dish of fish, prawn, or chicken curry has to be on the menu. While Indian curry is hot, rich, and fiery, with yogurt added, the Malays opt for a milder, delicate taste, with the creamy flavor of coconut milk in generous portions.”

In Malaysia, the curry concept is taken a step further with an impressive array of curry-like sauces. For example, lemak kuning is a coconut-based sauce made with most of the regional curry ingredients; kerabu kerisik is made with fried, pounded coconut, lime juice, dried shrimp, shallots, and chiles; and kacang blends together the flavors of peanuts, lemongrass, galangal, chiles, and coconut milk.

Similarly, the famous sambals range from simple chile sauces to curry-like pastes and are primarily used to spice up other dishes, such as mild curries. The basis for most sambals is chiles, onions (or shallots or garlic), and citrus, but many other ingredients are used including lemongrass, blacan, ginger, galangal, candlenuts, kaffir lime leaves, and coconut milk. Thus the sambals resemble a curry paste, but with a much greater amount of chiles. When made in the west, cashews (botanical at left) are often substituted for the hard-to-find candlenuts and now have become a curry staple.

Indonesian cookery is similar to Malaysian because they share many common ingredients: coconut, chiles, ginger, galingal, and tamarind, in particular. The Indonesian version of prawn paste is called trasi and is commonly used, as are a bewildering number of Indonesian sambals.

A wonderful description of the effects of Indonesian curries appeared in a nineteenth century travel book, The Boy Travelers in the Far East, by Thomas Knox: “This is the famous Java curry; and if you have taken plenty of the pepper and chutney, and other hot things, your mouth will burn for half an hour as though you had drunk from a kettle of boiling water. And when you have eaten freely of curry, you don’t want any other breakfast. Everybody eats curry here daily, because it is said to be good for the health by keeping the liver active, and preventing fevers.”

Hawkers, Chefs, and Tiffin Curries

In 1991, Mary Jane and I traveled to Singapore to experience the foods of the Spice Islands and to collect curry recipes. The night we arrived, friends immediately drove us the Newton Food Centre for dinner. Newton is one of the famous hawker centres–so named because in the past the cooks would “hawk” their food to customers. The centre consisted of perhaps fifty open-air stalls and a hundred tables and was jam-packed with hungry diners.

Intense and exotic aromas wafted from the food stalls which sported an intriguing array of signs, such as “Juriah Nasi Padang” and “Rojak Tow Kua Pow Cuttlefish.” The hawkers in a bewildering selection of quick and inexpensive foods from many cuisines. Among the delicacies we tasted were Chinese thousand-year-old eggs, the famous Singapore chile crab, Indonesian satays, Indian curried dishes, and a barbecued Malayan stingray.

in a bewildering selection of quick and inexpensive foods from many cuisines. Among the delicacies we tasted were Chinese thousand-year-old eggs, the famous Singapore chile crab, Indonesian satays, Indian curried dishes, and a barbecued Malayan stingray.

Later, at the famous Raffles Hotel (left), we learned about the evolution of another curry style in Singapore and parts of Malaysia. The “tiffin curry lunches,” still served at Raffles and other hotels, actually originated in India, where men went to work

carrying a tiffin carrier, a stacked series of containers (enamel or stainless steel) held together by a metal frame. The concept was brought to Singapore by the British, because they were loathe to dine in local establishments for fear of tropical diseases such as typhoid, cholera, and dysentery.

carrying a tiffin carrier, a stacked series of containers (enamel or stainless steel) held together by a metal frame. The concept was brought to Singapore by the British, because they were loathe to dine in local establishments for fear of tropical diseases such as typhoid, cholera, and dysentery.

The Malaysians have a saying, “Good food and happiness go hand in hand.” I hope our fellow cooks will find happiness with the Spice Islands curries that follow. Just don’t stuff yourself!

Indonesian Chile Paste

(Sambal Badjak)

This curry-like paste is used to add heat to curries or other dishes. There are many types of sambals in Indonesia, ranging from simple blends of chiles and shallots to the more complicated pastes such as this one.

8 to 10 fresh red chiles, such as serrano or jalapeño, seeds and stems removed

2 medium onions, chopped

4 cloves garlic, chopped

1 teaspoon shrimp paste or prawn paste

5 candlenuts (or substitute macadamia nuts or cashews)

1 teaspoon tamarind concentrate

1 small piece galangal, peeled and chopped (or substitute ginger)

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon brown sugar

2 kaffir lime leaves, crushed

1 cup thick coconut milk, recipe here

In a food processor or blender, combine the chiles, onions, garlic, shrimp paste, nuts, tamarind concentrate, and galangal, and puree to a fine paste.

Saute the paste in the oil until aromatic, about 3 to 4 minutes, add the remaining ingredients, and simmer for about 15 minutes, or until the mixture thickens.

Yield: About 1 1/2 cups

Heat Scale: Hot

Curry Puffs

Here is a curried accompaniment that differs greatly from the other curried dishes from the Spice Islands. They are commonly sold as a snack by street vendors, served at tiffin curry lunches, and sampled at afternoon teas. They make a superb appetizer.

Filling:

1/2 pound lean ground beef, lamb, or pork

1 onion, minced

2 medium potatoes, peeled, boiled and diced

1 teaspoon Indonesian Curry Paste (see recipe, above)

1/2 cup coconut milk, recipe here

Fry the meat and the onions together in a pan until the meat is browned.

Add the remaining ingredients and cook over medium heat, uncovered, until all the liquid has evaporated, about 10 minutes.

Drain the mixture through a sieve to remove all the remaining oil and set aside.

Pastry and Assembly:

2 cups flour

Pinch of salt

1/2 teaspoon baking powder

1 tablespoon butter

1 egg, beaten slightly

Water

Vegetable oil for deep-frying

Sift the flour, salt, and baking powder together. Cut the butter into the mixture until it resembles bread crumbs. Add the egg and enough water to make a dough and knead for 5 minutes.

Separate the dough into balls about the size of a walnut. Roll out the balls on a floured board into thin rounds about 4 inches across.

Place about one tablespoon of filling on each round and spread it over half the round. Fold the other half of the round over, wet the edges with a little water, and crimp with a fork.

Deep fry the rounds in hot oil, turning until both sides are brown. Drain on paper towels and store in a 325 degree oven until read to serve. They should be served hot with a sambal or hot sauce on the side.

Yield: About 20 puffs

Heat Scale: Mild to medium

Curried Coconut Beef

(Rendang)

This recipe, featuring beef simmered for hours in coconut milk and fresh curry spices, undoubtedly was prepared with water buffalo in its original form, since beef is uncommon in Malaysia and Indonesia. It is also spelled randang. Note: This recipe requires advance preparation.

4 ounces fresh coconut, grated

Vegetable oil for deep frying

2 pounds beef, cut into 1-inch cubes

1 teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons sugar

1 teaspoon tamarind concentrate

1 teaspoon ground turmeric

2 kaffir lime leaves, crushed

2 4-inch stalks lemongrass, bulb included, chopped

2 3-inch pieces galangal, peeled and chopped (or substitute ginger)

10 shallots, peeled and chopped

5 fresh red chiles, such as serranos or jalapeños, stems removed

2 cloves garlic, peeled

1 tablespoon brown sugar

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

2 teaspoons soy sauce

6 cups coconut milk, recipe here

In a fryer, deep-fry the coconut in the oil until dark brown.

Combine the coconut, beef, salt, sugar, and tamarind concentrate and marinate in the refrigerator for at least three hours.

In a food processor, combine the turmeric, lime leaves, lemongrass, galangal, shallots, chiles, garlic, brown sugar, salt, black pepper, and soy sauce, and puree to a fine paste.

Saute the paste in a large pan for 2 minutes, add the marinated beef, and saute for 5 minutes. Add the coconut milk, reduce the heat, and simmer, uncovered, for about 2 hours, or until the beef starts to fall apart and the gravy thickens. Add more water if necessary.

Yield: 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

White Chicken Curry

(Gulai Putih)

This lovely dish from Sumatra is popular in Singapore, where cashews and almonds are combined with the candlenuts. Some versions of this dish omit the chiles, which is very unusual in Spice Islands curries. Note: This recipe requires advance preparation

6 cloves garlic, minced

1/2 teaspoon turmeric powder

1 teaspoon salt

2 1/2 cups coconut milk, recipe here

1 3-pound chicken, cut up into 3/4-inch cubes

5 small dried red chiles, such as piquins, stems and seeds removed (optional)

4 shallots, peeled and chopped

1 small piece galangal, peeled and chopped (or substitute ginger)

1 whole clove

6 cashew nuts

6 almonds

6 candlenuts (or substitute macadamia nuts or cashews)

1/2 teaspoon cumin powder

1/2 teaspoon coriander powder

1 curry leaf (optional)

3 tablespoons ghee (recipe here) or vegetable oil

3 bay leaves

2 stalks lemongrass, bulbs included, left whole

1-inch cinnamon stick

Combine the garlic, turmeric, salt, and 1 cup of the coconut milk in a non-reactive bowl and marinate the chicken in the mixture for at least 1 hour.

In a food processor, combine the chiles, shallots, galangal, clove, nuts, cumin, coriander, curry leaf, and 1/2 cup coconut milk and puree to a fine paste.

Heat the oil in a large saucepan or wok, add the paste, and stir-fry for about 5 minutes. Add the chicken, 1 cup coconut milk, and the remaining ingredients and cook, uncovered, over low heat until the chicken is tender, about 40 minutes. Add a little water if the curry starts to dry out. Remove the bay leaves, lemongrass, before serving, leaving the cinnamon stick as a garnish.

Yield: 4 to 6 servings

Heat Scale: Medium

Prawn Curry

(Gulai Udang)

In Malaysia, this dish is sometimes prepared with as many as forty small, red-hot chiles, making it one of the hottest dishes in the Spice Islands. I have toned it down a bit, but it is still quite hot. In some versions of this gulai, tomatoes and/or tamarind paste are added. Serve the curry in banana leaves for a dramatic presentation.

10 dried small hot red chiles, such as piquins, stems removed

5 candlenuts (or substitute macadamia nuts or cashews)

2 stalks lemongrass, bulbs included

1/2 teaspoon turmeric powder

1 large piece galangal, peeled and chopped (or substitute ginger)

1 small onion, chopped

1 teaspoon prawn or shrimp paste

1 tablespoon ghee (recipe here) or vegetable oil

4 curry leaves (optional)

1 1/2 pounds prawns or large shrimp, peeled, heads and tails removed (optional), deveined if desired

1 1/2 cups thick coconut milk, recipe here

In a food processor, combine the chiles, nuts, lemongrass, turmeric, galangal, onion, and prawn paste and puree to a fine paste.

Heat the oil in a skillet or wok and fry the paste and curry leaves for 5 minutes. Add the prawns and coconut milk and cook, uncovered, over medium heat until the prawns are done, about 15 minutes.

Yield: 4 servings

Heat Scale: Medium to hot

Singapore Fish Head Curry

Although it does not sound particularly appetizing, this South Indian curry, transformed a bit by Malaysian ingredients, is truly delicious–if guests can get accustomed to the fish’s eyeball staring at them! I devoured this in an Indian-style recipe in Singapore, but Mary Jane averted her eyes! A readily available fish that works well in this dish is red snapper. Diners, eating communally from a single bowl, pick the meat off the head with a fork or chopsticks, then dip the meat in the curry sauce and place it on the rice on their plate, then eat it.

1/4 cup vegetable oil

2 curry leaves, crushed (optional)

1-inch piece galangal, peeled and grated, or substitute ginger

2 cloves garlic, chopped

2 medium onions, sliced

1 cup coconut milk

1/4 cup Indonesian Curry Paste, recipe above

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon sugar

3 tomatoes, coarsely chopped

2 teaspoons tamarind paste dissolved in 1 cup water

3 small, fresh, hot green chiles, such as serrano, seeds and stems removed, cut lengthwise in half

1 large fish head (about 1 pound)

6 small okras, parboiled and sliced

Heat the oil in a wok and fry the curry leaves and galangal for two minutes. Add the garlic and onions and fry until the onions are soft. Add the coconut milk and curry paste and stir-fry for about 5 minutes.

Add the salt, sugar, tomatoes, and tamarind and cook for 5 minutes. Add the chiles, fish head, and okra and simmer, uncovered, until the meat starts to fall off the fish head, about 45 minutes.

Yield: 2 to 4 servings

Heat Scale: Hot