By John R. Watkins, Photos by Howe, Atlanta, Georgia

No one who has had the good fortune to attend a barbecue will ever forget it. The smell of it all, the meat slowly roasting to a delicious brown over smoking fires, the hungry and happy crowds waiting in patience until the spits are turned for the last time, and the clatter of thousands of dishes as they are set upon the long tables before the hungry multitude—all this lingers in the memory, and makes one long to see a “cue” again.

For “cue” is what they call it in Georgia, where it has been famous for many, many years. England has its roast beef and plum pudding dinners, Rhode Island its clambakes, Boston its pork and beans, but Georgia has its barbecue which beats them all. So famous is it, in fact, that it has become a social and political force, and as a political entertainment has been duplicated in many States of the Union, but, alas ! without the Georgian glory of the thing. Dinners, it is said, are good things to do business with. What political power you can exert, then, if you invite two, three, or ten thousand people to a barbecue, and after filling them with good oxen or sheep, talk to them on the political questions of the day, and introduce your candidates to them!

It is with a view to show the Gargantuan scale on which these remarkable festivities are carried out that we have chosen the pictures which illustrate this article. Be it known, then, that we are in Georgia for the moment, waiting with the aforesaid hungry crowd for a sweet and tasty bit of meat. For a hundred feet or more, as we may see in the accompanying illustration, two long trenches have been dug in the ground and bordered with planks. Upon these planks, over a steady-burning fire, hundreds of sticks of wood, or “spits,” are laid, and on each of these spits is a sweet and tender sheep. We may marvel al the mass of meat, but we must remember the thousands of mouths to feed and appetites to satisfy. As a matter of fact, the waste at a barbecue is wonderfully small, for the men in charge know their business. They have been at barbecues before.

Good cooking requires constant attention, and the chef of a barbecue never relaxes his vigilance from the time the fires are started until the delicacies are served. But he has the cooperation of scores of skilled assistants, who stand by the fires, turning the spits. Naturally, in the South, the negro element has a prominent place, and the chef at the barbecue which we are now describing was a full-blooded negro—a man of great ability and popularity. We now reach an illustration that may seem out of place because it shows a variety of iron pots and kettles in use. “What,” you may ask, “have pots and kettles to do with a barbecue ?” Much. Game was the early essentials for barbecues. Then, when bears, deer, and other game became rare, oxen, pigs, and sheep were used. These increased in great number the variety of good things to eat, and, according to the liberality of the hosts, the beef or mutton on the bill of fare was supplemented by fish, fowl, pork, vegetables, etc.

Many of these ingredients are used in the famous “Brunswick stew,” without which no modern Georgia barbecue is complete. The preparation of this stew, for which the pots and kettles are used, requires considerable skill, and the man who makes it is no inconsiderable personage during the festivities.

As has been said, the barbecue exerts no small political influence. It was introduced into New York politics, during the Presidential campaign of 1876, by the Republicans, and the idea has since been carried out by Democrats and Republicans alike in many other States. On this memorable occasion, however—to be exact, on October 18th, 1876 —two fine and bulky oxen were led through New York on their way to Myrtle Park, in Brooklyn, where they were killed in the afternoon. One ox weighed 983 pounds, and by eleven o’clock in the evening he was on the spit grand scale, part of the trenches over which over a fire of coke, roasting in most appetizing fashion. Two large iron pans, parallel to the spit, held the fire. In order that the fire should not burn directly under the carcass, an iron peaked roof was arranged about 2 feet from the fire, flames being thus directed towards all parts of the ox. By eight o’clock on the morning of October 20th, the first ox was ready and was removed for cooling.

The second ox, a thousand-pounder, was now placed upon the spit, while the number of visitors to the curious scene began steadily to increase. By noon there were over a thousand, and the festivities began. Everybody was invited to partake of the feast, which consisted of sandwiches, for which the first ox had been cut up. Eight hundred loaves of bread were used in the operation, and although it reads like a fairy tale, the invited guests ate so greedily that in twenty minutes all that remained of the feast were the bones of the animal. The second ox was divided up at night in the presence of 50,000 people, while five speakers (with a political purpose) were spouting from different platforms in the grounds. It was one of the largest barbecues ever held, and ended in a blaze of enthusiasm and gastric satisfaction.

When thousands of people are expected at the feast, it takes some trouble to keep the dishes warm. This, too, is done on a grand, part of the trenches over which the meat is cooking is devoted to this purpose. In the foreground of the illustration we may see two score huge dishes filled with meat, potatoes, and vegetables placed on spits over the fire, while in the background we may see as many more. And this, be it remembered, is but a part of the whole.

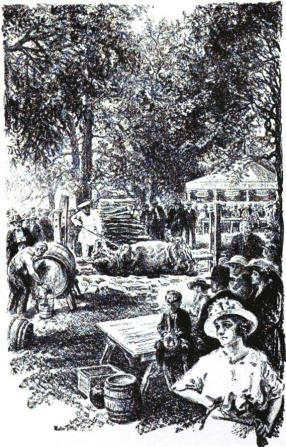

The feeding takes place both indoors and out, according to the weather, and we may pass on to two illustrations showing both sorts. The above illustration shows a banqueting hall with tables laid to accomodate three thousand people at one sitting. One may not easily imagine the number of dishes, knives, forks, spoons, cups, saucers, napkins, and glasses which are used on such occasions, but in one barbecue alone which I know of, over thirty thousand pieces were handled by the dish-washers after the people had gone home. One can, however, imagine the noise and clatter, the merriment and good feeling, which prevailed at such a time. During the Atlanta Exposition, a daily barbecue was held, to the delight of many visitors who had never seen a barbecue before. One of the most notable of these Atlanta barbecues was that given to 1,000 commercial travelers—an al fresco barbecue, as shown in the illustration below, and one that passed off without a hitch. Depend upon it, if a commercial traveller likes a barbecue, a barbecue is good.

A few figures and facts picked at random from newspaper accounts of these festivities will give some additional idea of their size and nature. On September 25th, 1884, a grand Democratic barbecue was given at Shelbyville, Indiana. Over 40,000 people were present, and 6,000 sat down, the meeting ending up with a torchlight procession. In March, 1888, a grand rabbit “drive” in California ended off with a barbecue, to which all the rabbit-chasers were invited. In many parts of Georgia, where the white farmers sometimes live two or three miles apart, a birthday will be celebrated by a barbecue, or a few families will join together in friendly communion, with a roasting hog or sheep in the centre.

There is, of course, an intermediate stage between the roasting of the meat and its delivery to the tables. No one could eat a whole sheep; therefore, when all barbecues are in progress, a certain place is sacredly set aside for the man who chops the meat in little pieces. He is a stalwart fellow with a massive cleaver, and for hours the monotonous chop, chop, of this deadly blade may be heard by the hungry crowd. He stands at a huge chopping-block, with hundreds of piled-up plates before him, while his faithful colored cohorts bring in, one after another, the smoking sheep, just as they are lifted and carried on the spits from the fire. Burnt fingers abound in the coon brigade, but cut fingers never. The stalwart chopper is too clever by far to mutilate himself when mutilating mutton.

When a barbecue is served out of doors, and there is no great formality about the feast, every man is expected to bustle round for his own platterful. The kitchen, at such times, is, of course, a sight, much as at a swell reception, when “refreshments” are served. The work of serving, however, is done on a system, and in the twinkling of an eye almost a line of men is formed, two by two, each with two platters in his hand, filled with the hot and luscious dainty of the day. With stately walk, the procession moves slowly from the kitchen out into the grounds, there, with wives and children, to eat the barbecue. Such a procession may be seen on this page — but what we see is only a portion of the crowd. Could we wait a few moments we should wonder when the end of the procession would come.

Finally, however, the procession gets seated at the table, hundreds of feet long, and disappearing in the distance like a railway. The foliage of the trees hides the hot sun from view, and, for an hour or more, the enthusiastic crowd dines to its heart’s content. Cooling drinks flow in abundance, the crowd grows merry, and,-as the last mouthfuls are taken, men, women, and children thin out and are off to their homes, or to hear the speeches of the day.

These speeches, as we have said, are almost wholly confined to political subjects, and barbecue orators are as much a class by themselves as Socialist and Anarchist agitators. This is not writ in condemnation, for at a barbecue you will hear more than a little common sense and truth. The populace must certainly believe so, for it is no exaggeration to say that many a gubernatorial election in Georgia has been carried by means of votes gained at barbecues, and no campaign for Governor is complete without a series of such popular feasts. Many a Senator and Congressman owe their political prominence to a popularity born and nurtured during these celebrations, and when a grand barbecue is on the tapis, there is no man quicker to respond with his money and his influence than the politician.

Such festivities, moreover, are not to be had for a song. Unless some bloated millionaire is willing to donate a flock of sheep to his fellow-men, the mutton has to be bought at market price. The dishes have to be hired, the service paid for, and the rent, both of buildings and grounds, has to be met. When barbecues are open to the public, as at the Atlanta Exposition, an admission fee is naturally charged, and expenses are paid in this way; but when votes are wanted, no charge is made, or, at least, such a trifle only as will serve to keep out the canaille. [Fr.: the rabble]

The end of a barbecue is a great time for the [negroes]. While others are listening to words of political wisdom from the mouths of golden orators, the little blacks silently and successfully approach from the four points of the compass, and set to work upon the scraps of good food which yet remain. They stop at nothing. Barbecues may come often, but they are always good, and the last drop from an empty barrel is often the sweetest of drinks.

From: The Strand Magazine (London), Volume 16, Publisher: G. Newnes, 1898, 463-468.

For more stories and photos of Eyewitness Historical Barbecue, go here.