Edited by Dave DeWitt

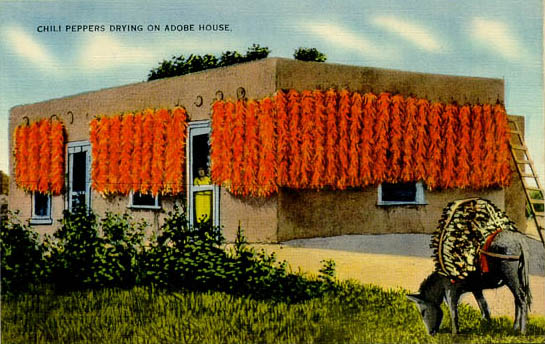

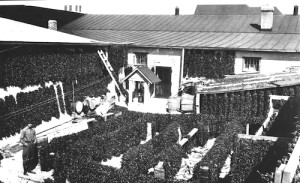

The men of this rancho had all gone to the war and the house was full of women, who made supper for us all. We were twelve in number. We had tortillas, frijoles, and carne seca, stewed up, with chile Colorado. My readers may translate these terms for themselves. To me, it was all very delicious till I helped myself to what I thought was a dish of tomatoes. It was pure chile—red pepper. It was fire itself. I was burning all the way down and up and every other way. I jumped from the table and ran for the creek. Finally, by copious use of the cold water, I quenched the heat, and went back to the house to find all the women laughing at me. –Jacob Wright Harlan, California ’46 to ’88. San Francisco: The Bancroft Company, 1888.

***

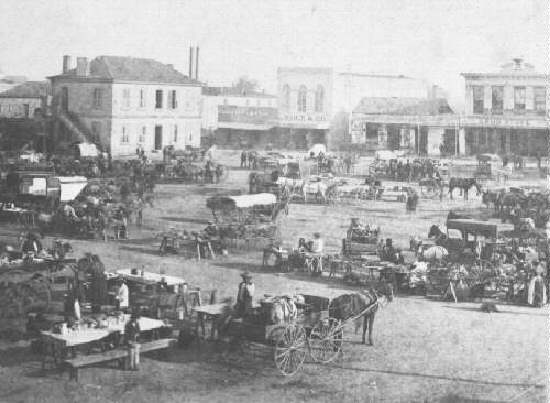

The sutler-woman, in bringing round to us for sale large earthen jars of hashed mutton, “chile,” and tortillas, would first serve to their own officers a saucer full generally for a medio, the sixteenth of a dollar, which they would eat with their fingers. There are only a few of the richest people in Mexico who own knives and forks, and the most of them handle them with as little grace as a cornfield negro would a rapier. The tortilla is a cake of bread made of Indian corn, about the thickness of upper leather, and quite as pliant. This cake not only serves the Mexicans as bread, but answers the triple purpose of knife, fork, and spoon: he with surprising dexterity will tear off a piece, and with his thumb and the two first fingers of his dexter hand, the fore finger being in the centre, so as to give it a spoon shape, dip up the red chops, and at every dip a new spoon disappears. The immense quantity of chile, “red pepper,” used in cooking gives everything cooked more the appearance of being submerged in a paint-bucket of oil and red lead than eatable gravy. –Thomas Jefferson Green, Journal of the Texian Expedition Against Mier: Subsequent Imprisonment of the Author; His Sufferings, and the Final Escape from the Castle of Perote. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1845.

***

The Mexicans seem to have stomachs made from leather judging from the way they endure excessive drinking, smoking (both men and women indulging in both), and the amount of chile they use. This chile is similar to our pepper. I know that it is awfully hot stuff and must be very injurious to the mucous membrane of the stomach. If I ate one-tenth as much at a time as a native would, it would take the roof off my mouth. I shall never forget my first experience; it was while we were staging and we stopped to change mules and get dinner. It was an entirely Mexican establishment except the American beer which gets even way down here. Well, I began eating,—there were two Americans, one a Dr. Norris of New York, and two Mexicans traveling with me—and Dr. Norris asked me to try the chile pronouncing it very good (he has been in this country before), the Mexicans also said the same. I went at it very charily. It is a suspicious-looking article the way they prepare it. I ate and it seemed that there might be some trace of cantharides on the roof of my mouth. They remarked that is nothing and keep right on, might just as well begin now as later. The Mexicans kept on laughing. Nothing daunted, I kept bravely on, determined not to give up before them. But I didn’t care for any more chile for one while. A Mexican dinner is enjoyable nevertheless for a change. –Paul Opperman, El Oro, Mexico, July 16, 1896. Cleveland Medical Gazette, Volume 11, 1896.

The Mexicans seem to have stomachs made from leather judging from the way they endure excessive drinking, smoking (both men and women indulging in both), and the amount of chile they use. This chile is similar to our pepper. I know that it is awfully hot stuff and must be very injurious to the mucous membrane of the stomach. If I ate one-tenth as much at a time as a native would, it would take the roof off my mouth. I shall never forget my first experience; it was while we were staging and we stopped to change mules and get dinner. It was an entirely Mexican establishment except the American beer which gets even way down here. Well, I began eating,—there were two Americans, one a Dr. Norris of New York, and two Mexicans traveling with me—and Dr. Norris asked me to try the chile pronouncing it very good (he has been in this country before), the Mexicans also said the same. I went at it very charily. It is a suspicious-looking article the way they prepare it. I ate and it seemed that there might be some trace of cantharides on the roof of my mouth. They remarked that is nothing and keep right on, might just as well begin now as later. The Mexicans kept on laughing. Nothing daunted, I kept bravely on, determined not to give up before them. But I didn’t care for any more chile for one while. A Mexican dinner is enjoyable nevertheless for a change. –Paul Opperman, El Oro, Mexico, July 16, 1896. Cleveland Medical Gazette, Volume 11, 1896.

***

But a dish more generally eaten than any other is meat cooked with red pepper, called “chile con carne.” It is perfectly red, and, at times, even strong enough to sear the throat in its downward passage. Should tears come in the effort to eat it, just let them flow, but go on with the mastication. In this, as in all other things (perseverantia omnia vincit), “perseverance overcomes all things.” It is truly wonderful how the human system will accommodate itself to such edibles, but it does, and survives the burning ordeal. I have seen the red pepper pods cooked themselves, and these are eaten with a great relish. They are fried or baked, and have the appearance of cooked tomatoes. These, I have thought, are not so strong, so fiery as the red pepper we find in the States, and hence, the eater survives his meal. This red pepper is served with dried jerked beef, and I must say makes it more palatable, “When the dose is given in moderate quantities.” –J. R. Flippin, Sketches from the Mountains of Mexico. Cincinnati, Standard Publishing Co., 1889.

***

Just at sunset we came to the two houses which comprised Carnöe*, and were hospitably taken in by the poor Mexican at the second. I shall always remember Ramón Arrera, the first Mexican in whose house I began to understand the universal hospitality of these simple folk — both for his courtesy and for a very funny acquaintance I found there. You may be sure Shadow and I were ravenous by this time; and the prospect of appeasing our appetites looked to me very slender. This fear was confirmed when Señor Arrera led me to the kitchen for supper. Upon the lonely-looking table was only a cup of coffee, a dry tortilla (the everlasting unleavened cakes, cooked on a hot stone), and a smoking platter of apparent stewed tomatoes. Now if there is anything which does not appeal to my stomach it is stewed tomatoes; but I was too hungry to be fastidious. There was nothing wherewith to eat except an enormous iron spoon, and with starving and unseemly haste I ladled a liberal supply from the platter to my plate and swallowed the first big spoonful at a gulp. And then I sprang up with a howl of pain and terror, fully convinced that these “treacherous Mexicans” had assassinated me by quick poison–for I had very ignorant and silly notions in those days about Mexicans, as most of us are taught by superficial travelers who do not know one of the kindliest races in the world. My mouth and throat were consumed with living fire, and my stomach was a pit of boiling torture. I snatched the cup of hot coffee and swallowed half its contents–which aggravated my distress ten-fold, as any of you will understand who may try the experiment. I rushed from the house and plunged into a snowbank, biting the snow to quench that horrible inner fire. Poor Arrera followed me in astonishment, but smothering his laughter. What was the matter with the señor? I came very near answering with my six-shooter, but his sincerity was plain, and I listened to him. Poison? No, indeed, señor. That was only chile colorado, chile con carne, which liked to the Mexicans mucho — and to many Americanos tambien. And so it was — only the universal red pepper of the Southwest, red pepper ground coarse and stewed with little bits of meat; an ounce or so of meat to a pint of the reddest, fiercest, most quenchless red pepper you ever dreamed of! I let him lead me back to the house, but with no more thought of eating. I felt inwardly raw from lips to waist, and great tears rolled down my cheeks for hours. Shadow ate greedily of the dreadful stuff, but I slept that night on a stomach which was empty, but certainly did not feel lonely, and a solemn vow never again to look upon the chile when it was Colorado. But next morning when I came out to breakfast very faint and weak, there was only the platter of blood-red stew and the tortilla and the coffee. I gulped down the leaden tortilla, with frequent gulps of coffee, and sighed. I was very hungry. The chile con carne smelt very good, at least. Perhaps–and I took a bare drop upon the spoon and put it to quaking lips. Hmm! Not so bad! Still I remembered last night, and took two drops. Rather good! A spoonful — a plateful — another — in fine, when I was done, not a bit was left of that inflammatory two quarts upon the platter, and I actually wished for more! The chile “habit” is a curious thing. Simply agonizing at first taste, the fiery mess soon conquers such an affection as is never won by the milder viands, which are sooner liked and sooner forgotten. I never missed and longed for any other food as I did for chile when I got back to civilization. –Charles Fletcher Lummis, A Tramp Across the Continent. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1892.

Just at sunset we came to the two houses which comprised Carnöe*, and were hospitably taken in by the poor Mexican at the second. I shall always remember Ramón Arrera, the first Mexican in whose house I began to understand the universal hospitality of these simple folk — both for his courtesy and for a very funny acquaintance I found there. You may be sure Shadow and I were ravenous by this time; and the prospect of appeasing our appetites looked to me very slender. This fear was confirmed when Señor Arrera led me to the kitchen for supper. Upon the lonely-looking table was only a cup of coffee, a dry tortilla (the everlasting unleavened cakes, cooked on a hot stone), and a smoking platter of apparent stewed tomatoes. Now if there is anything which does not appeal to my stomach it is stewed tomatoes; but I was too hungry to be fastidious. There was nothing wherewith to eat except an enormous iron spoon, and with starving and unseemly haste I ladled a liberal supply from the platter to my plate and swallowed the first big spoonful at a gulp. And then I sprang up with a howl of pain and terror, fully convinced that these “treacherous Mexicans” had assassinated me by quick poison–for I had very ignorant and silly notions in those days about Mexicans, as most of us are taught by superficial travelers who do not know one of the kindliest races in the world. My mouth and throat were consumed with living fire, and my stomach was a pit of boiling torture. I snatched the cup of hot coffee and swallowed half its contents–which aggravated my distress ten-fold, as any of you will understand who may try the experiment. I rushed from the house and plunged into a snowbank, biting the snow to quench that horrible inner fire. Poor Arrera followed me in astonishment, but smothering his laughter. What was the matter with the señor? I came very near answering with my six-shooter, but his sincerity was plain, and I listened to him. Poison? No, indeed, señor. That was only chile colorado, chile con carne, which liked to the Mexicans mucho — and to many Americanos tambien. And so it was — only the universal red pepper of the Southwest, red pepper ground coarse and stewed with little bits of meat; an ounce or so of meat to a pint of the reddest, fiercest, most quenchless red pepper you ever dreamed of! I let him lead me back to the house, but with no more thought of eating. I felt inwardly raw from lips to waist, and great tears rolled down my cheeks for hours. Shadow ate greedily of the dreadful stuff, but I slept that night on a stomach which was empty, but certainly did not feel lonely, and a solemn vow never again to look upon the chile when it was Colorado. But next morning when I came out to breakfast very faint and weak, there was only the platter of blood-red stew and the tortilla and the coffee. I gulped down the leaden tortilla, with frequent gulps of coffee, and sighed. I was very hungry. The chile con carne smelt very good, at least. Perhaps–and I took a bare drop upon the spoon and put it to quaking lips. Hmm! Not so bad! Still I remembered last night, and took two drops. Rather good! A spoonful — a plateful — another — in fine, when I was done, not a bit was left of that inflammatory two quarts upon the platter, and I actually wished for more! The chile “habit” is a curious thing. Simply agonizing at first taste, the fiery mess soon conquers such an affection as is never won by the milder viands, which are sooner liked and sooner forgotten. I never missed and longed for any other food as I did for chile when I got back to civilization. –Charles Fletcher Lummis, A Tramp Across the Continent. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1892.

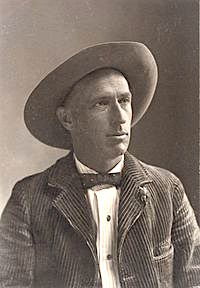

Editor’s Note: Charles Fletcher Lummis, above, almost always attired in his trademark well-worn, dark green, Spanish-style corduroy suit, soiled sombrero, and red Navajo sash, was one of the most famous and colorful personalities of his day as a book author, magazine editor, archaeologist, preserver of Spanish missions, advisor to President Theodore Roosevelt and a crusader for civil rights for Native Americans, Hispanics and other minority groups.

*Lummis is in New Mexico, still a U.S. Territory at the time. He is referring to the old name of Tijeras Canyon near Albuquerque, San Miguel de Carnué.

***

While breakfast was preparing next morning, some fiend suggested to one of our Mexican teamsters that the Americans might like a taste of Mexico’s standard dish, “chile,” of which, the fellow said, he had a good supply in his wagon-chest. Shamus was consulted, and assented at once, seeming delighted with the prospects of astonishing our palates with a new sensation. Know, O reader, of an inquiring mind, that chile consists of red pepper, served as a boiling hot sauce, or stew. It is believed to have been invented by the Evil One, and immediately adopted in Mexico. Shamus succeeded admirably in his design of concocting a sensation for us. Our alderman was ex officio the epicure of the party, half of his duties as a New York city father having been to study carefully all known flavors. He always tasted new dishes, and on our behalf accepted or rejected them. When, therefore, the savory stew came before us, he experimented with a mouthful. Immediately thereafter a commotion arose in camp, and Shamus fled before the righteous wrath of Sachem. –William Edward Webb, Buffalo Land: An Authentic Narrative of the Adventures and Misadventures of a Late Scientific and Sporting Party Upon the Great Plains of the West. Cincinnati & Chicago: E. Hannaford & Co., 1872.

Editor’s Note: And the legacy of all that chile eating? A tamale-shaped Mexican restaurant in Los Angeles, circa 1930; The Chili Bowl, Crenshaw, Los Angeles, 1931.