By William Agnew Patton

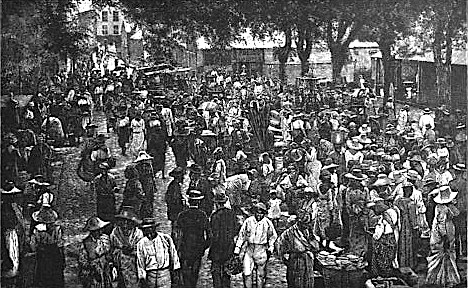

In the midst of this cooly district there is an open space, an acre or two in extent, densely shaded by a very ancient, and far-spreading banyan-tree, under the branches of which the cooly people hold their market. It would be impossible to imagine a scene more unlike any that I had ever beheld in all my travels in America or Europe. The people, their wares, their manner of trading, their baskets, trays, tables, their manner, voices, gestures, all were strange and outlandish, for the Hindus lose but little of their national characteristics in the New World. As I passed through the crowd the sellers saluted respectfully, bowing as they said, “Salaam, sahib;” then eagerly, but without clamor or violent gestures, besought me to purchase queer-looking eatables, utensils, ornaments, fabrics—in a word, all sorts of merchandise. There were venders of curry and curry-powder, purveyors of all kinds of food preserved in curry, curry to be taken away or to be eaten then and there—paper-packages, boxes, bottles of it, jars, pots, cups, bags, cocoanut-shells, full of curry—and everything, living or inanimate, in the market-place, was as distinctively East Indian as the curry itself, save and excepting a few Africans, Chinese, and Europeans, and their chattels and belongings.

“I say, old man, that pepper-pot isn’t half bad. I went in for such a lot of it—regular blow-out, by Jove! Awfully decent chaps. One of ’em told me how to make one. Get a lot of peppers, cayenne, bird’s-eye peppers, long, round, all kinds, green, red, yellow, such a jolly lot of ’em. Cut ’em all up. Makes my eyes water to think of it d’ye know!—I say, did you go in for it?” A pause, and inaudible remark by the “old man.” “Then you put this mess in a stone pot. Then, by Jove! fellow didn’t say—I forgot to ask if you cooked it —ask him on return trip—then you put in vinegar and catsup and spices, all that sort of thing—dash of bitters. No; that’s swizzle. By Jove! I say, did you go in for swizzle?” A very long pause; audible snore by the “old man.” “Then you take any blessed thing left over from dinner or breakfast, chop, leg of fowl, sausage, bacon (forget whether he said fish)—anything left of something too good to throw away or give to beggars, don’t you know. Tomatoes, pickles, all that lot. Only fancy! Any time you feel peckish—there yon are. It’s always going on, is pepper-pot; you never wash the blooming thing out; keeps for years. Decent old chappy that. Said it was good for dyspepsia and that sort o’ thing; only trouble is, you eat such a lot of it.”

To this formula I must needs add that casareep is a necessary and all-important ingredient of a right pepper-pot. Altogether, and under the peculiarly hospitable circumstances of his acquiring the knowledge how to concoct this West Indian olla podrida, my shipmate was not far out of the way. From his sketch of it, it will be seen that pepper-pot is a perennial free lunch, a perpetual zakooshka, a la Hiisse, a never-failing meal between meals; for, as my fellow-traveller said, it goes on forever, like the brook in the song, or a Chinese drama, and I can testify it is palatable. Moreover, if you are lined like a salamander you can eat such a lot of it, notwithstanding its blistering, peppery qualities, and in the day ye eat thereof ye shall not surely nor necessarily die.

From Down the Islands: A Voyage to the Caribbees, by William Agnew Paton. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1887.